150 Not Out

The Market for Newsletters (And a Peek Inside Net Interest)

When I launched Net Interest, in the throes of lockdown in May 2020, I had no idea what to expect. Since giving up managing money professionally a few years earlier, I’d retained a keen interest in financial markets and thought it would be fun to channel what I was looking at each week into a regular email. But finance is a niche hobby, especially the meta way I study it – through the lens of financial services companies – so I didn’t know how many people would follow me, nor how long I could maintain the cadence.

A hundred and fifty issues later, we’re still going strong. With close to 70,000 subscribers, Net Interest is a top ten finance newsletter on the Substack platform and one of the largest produced outside the US. My piece on Silicon Valley Bank went as close to viral as I’ve ever experienced, viewed by over half a million people and shared by many within the industry. Yet even before that, growth had been up and to the right, helped by kind comments from readers and endorsements from some serious people.

One of my favourite reader comments captures well what I strive for: “Your style is unique and special. It is dense and informationally rich yet easily digestible—an expert can learn, a novice can still understand. I personally don’t think anyone in financial journalism matches it.”

When I went paid on Labor Day 2021, I was even less certain of what to expect. I continued to release a lot of content for free to maximise growth while offering paid subscribers something extra. Since then, I have gradually raised the paywall, reserving timely company briefings such as those on Stripe, JPMorgan and West Coast Banks for paid subscribers. I am extremely grateful to all of you who value my work sufficiently to hit the subscribe button. Thank you.

To celebrate the milestone of 150 issues, I’d like to invite you behind the curtain into the world of paid newsletters. I’ll tell you a bit more about Net Interest, but we’ll also look at the overall market. Paid newsletters have a rich history, especially in finance; it’s a market that continues to grow.

Net Interest isn’t the first finance newsletter to grace inboxes and it won’t be the last:

📭 Charles Schwab’s first job out of college was as a contributor to a newsletter published by a Menlo Park-based firm, Foster Investment Services. Paid just $625 a month, Schwab saw upside in branching out on his own and, together with a colleague, went off to set up Investment Indicators, a biweekly investing newsletter. At launch, Schwab charged $60 for an annual subscription, hiking that to $72 once the letter was established. With peak subscriptions of 3,000, newsletter revenues topped out at $216,000 a year.

After buying out his financial sponsor, Schwab soon added a mutual fund and a small venture arm to the business, before taking it in a completely different direction. However, the newsletter stood him in good stead. “If I’d learned anything from all those years of publishing newsletters,” he wrote later, about the launch of his eponymous discount brokerage service, “it was how to do direct marketing.”

📭 Ray Dalio founded Bridgewater Associates, now regarded as the world’s largest hedge fund, out of his Manhattan apartment in 1975. Before it became a hedge fund, the firm operated as a risk consultancy and Dalio would produce daily written market commentaries as a door-opener. His newsletter – Bridgewater Daily Observations – was good enough to come to the attention of McDonald’s, which hired the firm to look at ways to hedge the price of chicken ahead of its launch of the Chicken McNugget. Even after he wound up the advisory side of his business and went into money management, Dalio continued to produce Daily Observations. Prior to 2006, a subscription cost $10,000 a year, although later the firm restricted access to investing clients only.1

📭 Tokushichi Nomura took over his father’s money changing shop in Osaka in 1904. His insight was that securities offered better return prospects than bank savings but that the public was put off by “the generally poor character of securities dealers, and the fact that their knowledge of the market was really quite limited.” Newsletters turned out to be a good solution to this problem. In 1906, Nomura hired an investigative journalist from the local newspaper to become Japan’s first research analyst. Their newsletter, the Osaka Nomura Business News, was distributed daily, replete with information on the previous day's trading, analyses of particular stocks, and articles on current economics trends. Nomura went on to become Japan’s largest investment bank and brokerage group.

In each of these cases, newsletters worked as a springboard into a more lucrative area of finance, be it brokerage or money management. Which makes sense. As I’ve discovered, newsletters engender a network of trust, a feature Tokushichi Nomura very explicitly targeted over a hundred years ago.

But it’s also possible to derive a perfectly comfortable revenue stream from newsletters alone. One firm attempting to do that at scale is MarketWise. The company was founded in 1999 by Porter Stansberry “on a borrowed laptop computer, on my kitchen table inside the third floor, walk-up apartment at 1823 Eutaw Place in Baltimore, Maryland in 1999.” (Funny how all newsletters start out the same way.)

Stansberry is a controversial figure. He was prosecuted in 2003 by the Securities and Exchange Commission for claiming to have inside information about companies which readers of his newsletters could cash in on. After paying a fine of $1.5 million, he continued to build his business, acquiring other newsletters and launching new products. By the time he resigned in 2020, he had grown his paid subscriber count to one million, making his company, “to the best of my knowledge, both the biggest and most profitable financial newsletter business of all-time.”2

Fellow newsletter writer Byrne Hobart has a view: “At the limit, any company in the business of selling bits will be good at either a) selling very high-quality bits, or b) being very good at selling. MarketWise would likely admit that they’re in the latter business.”

(Byrne, by the way, was the writer who most inspired me to launch Net Interest. I would recommend subscribing to his newsletter if you do not already.)

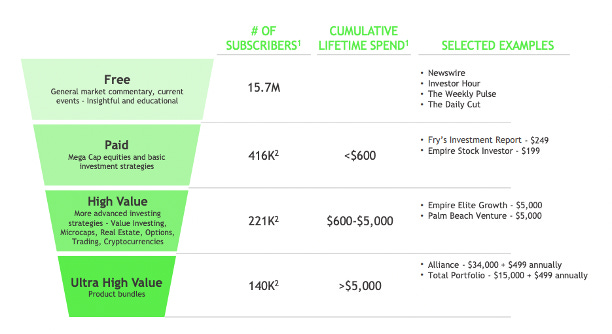

Being very good at selling enabled MarketWise to capture a $3 billion valuation when it went public via a SPAC transaction in 2021. The deal marked the top. Paid subscriber count has fallen to 777,000 as at the end of March, equivalent to a 4% conversion rate off the company’s 15.7 million free subscribers. Around half are relatively low value subscribers, with a cumulative lifetime spend of less than $600, although half are high value, with 140,000 “true fans” who spend over $5,000 each (some pay $34,000 up front).

All newsletters face the challenge of churn, and MarketWise is no exception. Net Interest has lost 8,500 (free) subscribers over its life, equivalent to 11% of gross subscriptions; I’d be hitting over 75,000 subscribers now if it wasn’t for the churn. Yet however protective people are over their inboxes, they are more protective over their wallets: Paid churn is higher.

In MarketWise’s case, subscriber churn has ranged between 1.8% and 2.7% per month over the past few years; it is currently at the higher end of that range. From a revenue perspective, that compounds: Only 40% of the billings initially secured from the 2020 cohort of customers were still active at the end of 2022.

This means the company has to run hard to stand still. In the past 12 months, it spent $215 million on marketing, but with customer lifetime value currently tracking at 2x customer acquisition cost – lower than the 3x most companies shoot for – that doesn’t leave much wiggle room for margin.

In spite of its issues, MarketWise still generates $500 million of annualised revenue. It also shines a light on the size of the newsletter market. The company has revised down its estimate of its total addressable market from $191 billion at the time of its listing to $60 billion today (evidence of its selling shtick again) but within that, it reckons that if a third of the self-directed investors in the US are willing to pay to bolster their financial markets knowledge, there may be $20 billion of revenue available.

The promise that a finance newsletter can provide its readers with some material financial upside is what sets it apart from the rest of the newsletter market. As you know, I purposefully steer clear of making investment recommendations, although I hope to provide inspiration. In that respect, Net Interest shares features both with the general newsletter market and, given my 25 years of experience in it, the market for institutional investment research.

Newsletter-like pieces include one of my all-time favourites, My Adventures in CryptoLand, as well as book reviews such as Trillions and The Power Law. Pieces that capture some of the attributes of investment research (some, not all; as discussed in Great Quarter, Guys, there are lots of jobs to be done in investment research) include frameworks such as How Markets Work and The Diary of a Bank Analyst, as well as company briefings on Visa, Worldpay, (unlisted) Klarna and many more (click here for a full index).

The challenge is that one of these markets is growing; the other is shrinking.

Newsletters are a growing market. The platform I use, Substack, has 35 million active subscriptions across the newsletters it hosts, of which 2 million are paid (end March). In 2021, the company earned $11.9 million of gross revenue. On its standard writer contract, Substack takes a 10% cut of subscription fees but, in 2021, it also offered writers a minimum guarantee for a 12-month period in exchange for 85% of the economics. With $6.3 million of revenue booked on the standard contract and $5.5 million on the guaranteed contract, total subscription fees in 2021 can be estimated at $69 million.

For writers, it’s a good deal. Adding the guaranteed payouts ($16.7 million in 2021) to their share of the fees and deducting payment processing charges, Substack writers in aggregate took home around $71 million in 2021. The company hasn’t disclosed financial information for 2022, but it has signalled that cumulative money paid to writers was around $265 million as at the end of 2022, which implies around a further $185 million paid out to writers last year, taking into account what was paid out prior to 2021.

Monthly active subscriptions continue to rise, so the growth is clearly evident. Earlier this year, Substack raised money at a $655 million post-money valuation, roughly equivalent to the current market value of MarketWise despite being about half the size in terms of the subscription fees it generates.

Such growth contrasts with the squeeze in institutional investment research. In the past, the price of institutional-grade research was opaque because it was bundled into the cost of trading. The model derives from the era of fixed brokerage commissions in the 1960s and 1970s when brokers had to find features other than price to differentiate themselves and research emerged as a big one.

Having survived deregulation and ongoing compression of commission rates, and then scrutiny from the New York Attorney General in the aftermath of the dotcom bust, the model came unstuck when European authorities insisted that research be cleaved apart from trading in the MiFID laws of 2018. It’s a theme we discussed early on in Net Interest in The Cautionary Tale of Equity Research and it’s one I returned to this week in an article for Bloomberg.

Even though European lawmakers now realise they made a big mistake (the rules “might have impaired the overall availability of research,” they admitted late last year) they created a window for price discovery. For many independent firms, the process was a shock as larger integrated firms drove down the price of research. In the run-up to MiFID, JPMorgan offered access to its global research for as little as $10,000 per year.

The result has been a shrinking market. According to Integrity Research, the institutional investment research market is currently worth $13.7 billion, down from a peak of $17 billion in 2015. Most of the market is captured by sell-side brokerage firms ($11.5 billion) but independent firms share $2.2 billion between them. The models they employ vary.

This week, Zoltan Pozsar, a well regarded money markets analyst, announced that after leaving Credit Suisse, he is in the process of setting up his own research firm, Ex Uno Plures. His price point: $30,000. “It’s a high price tag so, you know, the target audience is institutional investors exclusively and not retail investors. And so I will be completely behind the paywall and subscribers will be able to chat with me and have conference calls and meetings. And that’s basically the simple vision.”

Meredith Whitney is another independent analyst, also in the process of launching a firm, Meredith Whitney Advisory Group. Like Pozsar, she made a name for herself during the Global Financial Crisis although she has been out of the market since winding up her former research boutique in 2014. Unlike Pozsar, she leans more towards the retail end of the market: $3,084 per year gets you monthly long-form thematic research papers, weekly short-form papers on timely events and invitations to special feature events.

I think that $25 per month for Net Interest is extremely good value. Sure, there’s not going to be a banking crisis every year (or is there?) but as I wrote in my very first piece, financial companies are everywhere and if I can provide clarity around them, I’m happy.

If you’re an existing paid subscriber, thank you. I’ve set up a referral scheme, so if you have friends or colleagues who would appreciate Net Interest, send them along and you could earn rewards.

I also have a few institutional subscriptions left at an annual rate of $5,000. Existing clients include firms in Europe and the US that between them manage aggregate assets of $13 trillion. If your firm has a research budget and you have colleagues who would value access to Net Interest and to me personally, please get in touch for more details.

Finally, I would be delighted to answer any questions you may have – about the financial industry, the newsletter industry and everything in between. So let’s trial a mailbag approach. If you are a paid subscriber, you can ask a question in the comments on any topic. I’ll pick some out and publish a post with responses over the summer.

Here’s to another 150!3

Dalio solved the chicken-hedging problem by creating a synthetic futures contract that combined the prices of corn and soymeal, and pitching it to a chicken producer. As long as the producer could keep those prices fixed, it could keep the price of chicken fixed – the chick itself was the lowest cost input in the manufacture of the chicken. Able to hedge its own costs, the producer was then in a position to quote McDonald’s chicken at a fixed price.

In January 2023, Porter Stansberry, who left MarketWise before its stock market debut, launched an activist campaign against the company. “There was a $3 billion IPO. And what did I get out of the deal? Bupkis.” In May, a settlement was agreed.

If you’re reading this, Ben Stokes…

Marc,

It would be interesting to compare the financials and KPIs of Substack versus other newsletter services (e.g., Beehiiv) and, more broadly, other content paywall gateways like Patreon and, um, Onlyfans.

Furthermore, on Substack, I suspect Elon Musk may want to strike a more conciliatory tone given the arrival of Threads, Zuck’s latest salvo in their METAphorical cage match.

Congratulations! I really enjoy reading your column every week.