So You Want to Launch a Hedge Fund?

Plus: Bank Earnings in the Aftermath of Crisis

Welcome to another issue of Net Interest, my newsletter on financial sector themes. This week we look at the hedge fund industry and after that – for paying subscribers – some preliminary comments on banks’ first quarter earnings. If you’re not already signed up, you can do so here:

Since winding up my hedge fund several years ago, I’m often asked whether I intend to return to the job of full-time investing. It’s a natural question and I’m not alone in thinking about it. Fellow Substack writer Russell Clark shuttered his own fund in 2021. In a series of posts published in February, he expressed little appetite to get back into the game.

Russell’s view is that the environment for fundamental hedge fund investing is not as conducive as it once was. He looks back on the time we both started at our former firms as a golden age, difficult to replicate. It was the mid 2000s and the overall market was coming off an elongated period of poor performance in the aftermath of the dotcom crash. In contrast, hedge funds were doing well. Equity hedge funds were up around 35% over the first five years of the decade, at the same time as the S&P 500 index was down.

It was against this backdrop that capital allocator Ted Seides made a bet with Warren Buffett that hedge funds would continue to outperform over the next ten years. Ted picked five funds-of-funds whose results were to be averaged and compared against the Vanguard S&P index fund backed by Buffett. Ted’s funds-of-funds owned interests in more than 200 individual hedge funds, making his picks a fairly representative sample of the industry. The loser would donate $500,000 to a charity of the winner’s choice. The bet kicked off in January 2008 and by the end of the first year, Ted was in the lead, his funds down 24% in a year the index was down 38%.

My own fund didn’t do too badly over that period either. In the three years 2007 to 2009, we were up 56% during which time the index was down 21%. The fund had been launched in 2004 and by the time I arrived in 2006, it had grown to $1.6 billion of assets under management. On the back of strong performance, assets continued to grow, rising to $4.1 billion at their peak.

The golden age spawned many more hedge funds. Alongside ours, 696 new funds launched in 2004. In the year Buffett’s bet commenced, 933 funds were launched and the year after, a record 1,006 new funds were set up as ambitious managers peeled away from established funds or left investment banking firms to try their hand in the hedge fund business.

But then hedge funds started to struggle against the market. Ted’s picks failed to beat Buffett’s index fund in any one of the remaining nine years of the bet. By the end of 2017, his funds were up just 38% while the index was up 126%. Buffett put the divergence down to fees. In addition to incentive fees, the hedge funds-of-funds extracted an annual fixed fee averaging 2.5% of assets. “Performance comes, performance goes. Fees never falter,” he concluded.

Ted took a different view, blaming other factors including global diversification. His funds invested globally and, over the period, international stocks massively underperformed the US S&P 500 index. Buffett’s “excellent choice of the S&P 500 for the bet was the main reason he won,” he wrote.

Either way, hedge funds began to look less alluring and the pace of new fund launches slowed. Last year saw just 166 new launches, the fewest since 1998. Yet, reflecting a cyclicality that is often evident in markets, 2022 turned out to be one of the best years for hedge funds in a long time. Equity hedge funds were down just 10% in a year when the S&P 500 index was down 20%.

So is now the time to launch a new fund?

The Business of Hedge Funds

The first thing you need to do as a new fund is raise some seed capital. Having a wealthy benefactor helps; failing that, it can be hard work. Dan Loeb of Third Point, a New York-based hedge fund focused on event-driven, value-oriented investing with $16 billion in assets under management, describes how he spent six months in the early 1990s driving around the country opening savings accounts at mutually held savings and loans companies which later demutualized, providing the seed capital for his fund. He financed the trades with bonuses he had accumulated at his prior investment banking job supplemented with borrowings.1

Loeb launched in 1995 with $3.3 million. These days, you need more.

When Paul Marshall and Ian Wace launched their firm, Marshall Wace, in 1997, they started with $50 million under management. The two were better connected than Loeb and were able to raise the funds comfortably. George Soros contributed half, and the other half came from friends and family. The firm now manages around $60 billion, but if they were to go again, Paul Marshall cautions it would be different: “The minimum scale of AUM required for a hedge fund to break even has risen sevenfold, from $50 million in 1998 to $350 million in 2018.”

One reason for the higher break-even is that it costs so much more to lay down infrastructure. Technology has had a deflationary effect on some cost lines, but it has bypassed others – Mayfair and Greenwich real estate, for example, as well as compliance.

According to one set of estimates I’ve seen, a portfolio manager wanting to set up shop in New York today, with four analysts and two employees in operations and support, would need to find around $500,000 in initial set-up costs as well as around $2.3 million a year in recurring charges. Even if some of those expenses can be passed on to end-investors, there’s still a large cost base to fund. Assuming a traditional 2% hedge fund management fee, breakeven would be around $100 million in assets. (Paid subscribers can email for details of the full budget.)

Which leads to a second challenge: fees are going down; the traditional 2% management fee is no more. Even in Paul Marshall’s day, it is likely that George Soros pushed a hard bargain. We’ve written before about how Soros offered BlueCrest Capital Management a 0.5% fee to manage his funds (BlueCrest refused). These days, the pressure to offer discounted rates to founder and anchor investors is greater. Most new funds offer a founder class at a management fee rate well below 1.5%. And even on the standard class, 2% is high for most new funds.

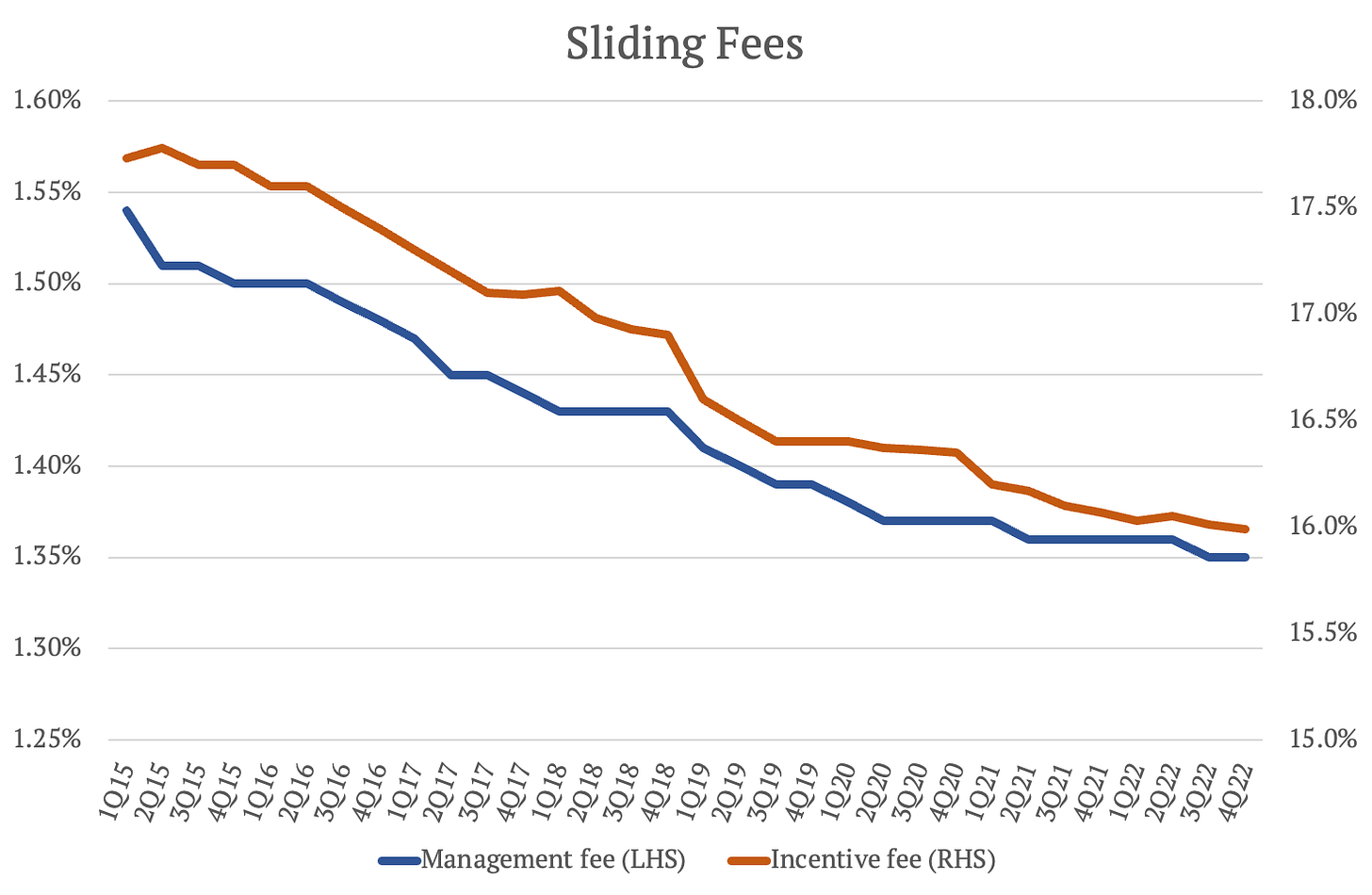

Across the universe of hedge funds, management fees now average 1.35%, according to data from Hedge Fund Research (HFR). On a 1.5% management fee, breakeven would be closer to $125 million and on 1.0%, around $190 million. Incentive fees have similarly gone down, from 20% to 16% by the end of 2022. Due to deflation, “2-and-20” is now “1.35-and-16”.

But let’s say you’re able to raise the funds and absorb the fee compression. What next? Well, staying in the game can be as hard as setting up. “Most fund management careers end in failure,” says Paul Marshall.

The challenge is that dealing with clients can detract from the business of investing. Many successful firms employ one partner to manage the business and another to manage the fund, but the demarcation is never that clear as clients usually want to speak to the one managing the money. This can place significant pressure on the fund manager.

Portfolio manager Dan McMurtrie, who launched a fund in 2015, spells it out (emphasis mine):

“I’ve watched 70, 80, 90% of [emerging managers] fail. Maybe two, I know, have failed from stock picking. It's never the stock picking. I’ve yet to really see a situation where I actually think the guy just picked shitty stocks.

“It’s always something like, they were trying to do fundraising, and that led to them not being able to really do adequate research for a few weeks. And they were also up late going to dinners and things like that, playing that game. And they were really burnt out and tired. And then something happened in their family. Somebody got sick or something like that… They haven’t really slept in eight weeks. They stopped working out. Their diet kind of goes to shit cause it’s all takeout, cause it’s near the office, right? They’re not drinking enough water. They haven’t taken a day off, away from screens, in six months.

“And you see these people who are geniuses become neurotic, borderline unfunctional people. And then, something happens and they can’t react to it. And they double down and they shouldn’t, they make basic mistakes. It’s like somebody going into a prize fight when they haven’t slept for six weeks, they can’t hold their hands up to box… They are non-functional, and they implode. Most managers implode rather than explode.”

The point is, running a business is hard, managing other people’s money is hard, doing both is quadratically hard.

Fortunately, there is an alternative.

Joining a Pod Shop

Ken Griffin is officially the most successful hedge fund manager in the world. In his 30+ years in the business, he has produced $65.9 billion in gains for investors, net of fees – more than any other manager.

He launched his firm Citadel in 1990 with just $4.6 million in capital after a short stint at another firm and after having famously begun trading from his dorm room at Harvard. Within eight years, the firm had grown to over $8 billion in assets under management. Today, he manages $57 billion.

Griffin’s success stems from him playing a different game from others in the industry. Over twenty years ago, one of his executives told Institutional Investor magazine that his goal was “to see if we can turn the investment process into widget making.” And that’s what he did.

Griffin was one of the pioneers of the “pod shop”. Alongside other firms like Millennium, Citadel, Point72, Balyasny and Schonfeld, he structured his fund around “pods”, each of which is allocated a slice of the firm’s assets to manage. The advantage is that portfolio managers don’t have to worry about managing the overall business, and business managers don’t have to worry about deploying funds in strategies where opportunities have diminished – they simply reallocate to more productive pods.

Dmitry Balyasny, founder of Balyasny Asset Management, which manages $19 billion of assets, says the model derives from a trading view of markets rather than a fundamental investing view:

“[Its] origins go back to my origins as a trader and thinking about how to build out business around trading… It makes sense to have lots of different types of risk-takers, because you have less correlation, you could attack different areas, the markets, and have specialists in different areas.”

These days, “pod shops”, or multi-strategy funds as they are formally known, are gaining market share. Last year, they collectively raised about $5.8 billion, while the industry as a whole recorded $111 billion in outflows, according to eVestment data.

The number of pods is growing commensurately. Balyasny employs around 1,600 people across 173 teams, up from 125 teams a year ago. Millennium Management – which this year leapfrogged Citadel by assets under management – employs 4,800 people across 290 teams. Millennium’s pod count is up 25% over three years, over which time the number of traditional hedge funds has shrunk. Some managers are even ditching their own funds to sign up as pods at multi-strategy firms.

For the manager, the trade can be appealing. They don’t have to participate in marketing meetings or invest in infrastructure – they simply get on with the task of investing. And because of the scale of these firms, the infrastructure is pretty good. “The Citadel toolkit, from data crunching tools to the proprietary risk model, optimises the time spent understanding businesses,” says a Citadel investment professional.

In return, managers get around an 18-20% payout on what they make. The downside is that they themselves are simply positions in a broader portfolio that constitutes the overall fund and, like positions in a portfolio, they can be discarded if they fail to perform. Their capital is typically cut when they are down 4-5% and they are cut when they are down more.

The result is a steady stream of uncorrelated returns that clients love. Over 33 years, Millennium has produced an average calendar-year return of 14% with only one loss year of 3.5% in 2008. Balyasny targets a 7% annualised volatility, which compares with ~18% for the S&P 500 index.

The funds have replaced the hedge funds-of-funds that Ted Seides bet on (one of which anyway closed shop before the bet ended). In theory, sophisticated clients shouldn’t need funds like this because they can replicate them by themselves via a portfolio of traditional funds – the same rationale as the stock market not needing conglomerates. But that’s not the way the world works; there is a premium on stability and those that offer it are able to scale more than those that don’t.

That premium is reflected in high fees. Earlier this year, Millennium changed its fee structure to ensure that clients always pay a minimum fee, even if the fund loses money. They will now pay annual fees of about 1% of assets or 20% of investment gains – whichever is greater. Like other firms, Millennium also passes along to clients expenses including some compensation costs and legal and accounting costs.

So the hedge fund industry is still pretty lucrative, but value is increasingly accruing to the platforms. Perhaps one day, there’ll be room for a Net Interest pod, but for now, I’ll stick to writing.

In the meantime, if any pods, or traditional managers, want to discuss what’s going on in the financial sector broadly, drop me a line; we still have a number of institutional subscription slots open.

Paid subscribers can read on for commentary about banks’ first quarter earnings - their first in the aftermath of the recent bank failures…