Peak Pod

The Industrialisation of Alpha

He’s not authorised to begin trading yet but, behind the scenes, Bobby Jain is getting ready. Formerly an executive at Millennium Management and a veteran of Credit Suisse, Jain is laying the groundwork for the largest hedge fund launch in history. By the time he starts, Jain is expected to have raised as much as $10 billion of client money. In preparation, he’s touring the world, locking down office space and securing talent; already he’s made a number of high-profile hires (all while overseeing his influential think tank, Jain Family Institute).

What’s unusual about Jain is that, unlike hedge fund moguls of the past, he has no Big Trade to his name. He didn’t make a fortune betting against the Bank of England or shorting subprime. He’s not the best business analyst in the industry or arbitrage trader or distressed credit investor, nor does he have a special mathematical algorithm for beating the market. In fact, he’s known less for his money-making skills than for his risk management and organisational skills.

But in the current hedge fund landscape, it’s risk management that pays. Investing clients can get market exposure (known as beta in the industry) for free through index funds. A stable stream of alpha (excess return) is more valuable and commands a significant pricing premium. The type of platform that Jain plans to launch, similar to the one he managed at Millennium, is the closest thing the market has right now to an alpha machine.

We looked at platforms such as Jain’s in So You Want to Launch a Hedge Fund? back in April. Known as multi-manager funds, they comprise a bunch of investment teams all operating autonomously under the umbrella of an overall firm. Capital is allocated from the centre as are the teams’ risk parameters.

The approach was pioneered in part by Ken Griffin. He set up his firm, Citadel Advisors, in 1990 with $4.6 million of capital (a fraction of what Bobby Jain hopes to start with, but then Griffin was barely out of college). Ten years later, one of his executives told Institutional Investor magazine that his goal was “to see if we can turn the investment process into widget making.”

And that’s what he did. Griffin recruited teams with narrow specialisations and backed them to trade their niche. Their job was not to take market risk but to outperform a benchmark by a few percentage points and not lose money. If they performed well, they were allocated more capital; if they performed poorly, capital was withdrawn or, worse, they were fired. Returns were aggregated in a central pool managed out of Chicago. One such specialisation was banking stocks; as a sell-side research analyst, I would regularly compare notes with the Citadel team (or “pod” as these teams became known) about the banks we followed.

Dmitry Balyasny, founder of Balyasny Asset Management is a more recent entrant to the industry. He attributes the model to a trading view of markets as distinct from an investing view (emphasis added):

“[Its] origins go back to my origins as a trader and thinking about how to build out business around trading… It makes sense to have lots of different types of risk-takers, because you have less correlation, you could attack different areas, the markets, and have specialists in different areas.”

My contact at Citadel clearly performed well because he was retained at the firm for more than ten years, before leaving to join Balyasny as Head of Equities. His trajectory reflects the overall growth in the multi-manager space. Citadel now runs $61.0 billion of capital, and Millennium – the other big player in the field – manages $59.3 billion. Point72 Asset Management is number three with $30.6 billion and Balyasny is fourth, with $19.5 billion. Millennium itself has over 300 distinct investment teams operating within its walls. Pod inflation has increased the number of teams looking at financial stocks from one at Citadel 20 years ago to eight or nine at Millennium today in London alone.

Because of leverage, the footprint these firms leave in markets is even greater than their assets under management suggest. In aggregate, the four largest firms had over $1 trillion of exposure at the end of March, according to regulatory filings. The forty or so firms that operate the multi-manager model may command only 8% of hedge fund assets but, according to Goldman Sachs, they account for 27% of the holdings of US equities (up from 14% in 2014).

This makes them “one of the largest gravitational forces in markets,” according to investment professional Patrick O’Shaughnessy – and therefore worth understanding.

So far, the model has worked extremely well. Citadel is ranked the most profitable hedge fund firm of all time (defined by the cumulative net gains it has produced for clients since inception) and Millennium has generated an average calendar-year return of 14% for the past 33 years, with only one loss year in 2008.1

But the question Bobby Jain will no doubt get on his roadshow of potential investors is whether the growth of the platform model – and more specifically the alpha it is able to capture – can be sustained.

Ken Griffin thinks not. “The stories of markets are always stories of cycles and strategies that come and go in terms of popularity,” he said in a recent interview. “Clearly right now the multi-strategy managers are very much in vogue. When you’re most popular is probably when you’re reaching the top of the cycle.”

To understand more about the multi-manager fund model and how the cycle may play out, read on.

The pitch

For a prospective hire at a multi-manager fund, the pitch is simple. Come and work for us and you don’t need to worry about all the boring stuff investment professionals typically have to do – marketing, operations and so on – you simply get on with the task of investing. “The Citadel toolkit, from data crunching tools to the proprietary risk model, optimises the time spent understanding businesses,” a Citadel employee might tell you.

Oh, and you’ll get paid well, too – if you perform. Teams at a multi-manager fund typically take home 15-20% of the profits they generate in addition to having expenses paid for. With a portfolio of $2 billion and a 5% annual return, a portfolio manager running a team can earn in excess of $10 million a year.

Increasingly, top portfolio managers are also being offered lucrative signing-on fees (in some cases as high as eight digits). With much of the talent at investment banks having been depleted, multi-manager firms have begun to point their recruitment efforts towards each other. Citadel recently attacked Balyasny for poaching several of its employees, alleging they took with them confidential information.

According to Will England, CEO of smaller competitor Walleye Capital ($5 billion in assets under management), there is only a “finite pool of talent” across the industry, probably “more hundreds than thousands” in number, so the industry’s growth means that it is now bumping against that limit. One long-term solution is training, which firms are taking more seriously. This summer, Citadel paid $19,200 a month to interns on its programme in Hong Kong.

Happily for the firms at the centre of this boom, they are able to pass on recruitment expenses to end clients. Indeed, this pass-through fee structure is a key feature of the model. Open up the regulatory documents filed by Balyasny, say, and you find a long list of expenses that are eligible to be passed on to fundholders. They include: compensation (including signing-on bonuses), recruiting-related expenses (good news for headhunters), legal fees, meals, relocation expenses, market data, research, technology, communications, and travel.

Loading that much expense onto the fundholder clearly raises the gross return hurdle required to generate a targeted net return, as the chart below demonstrates. Will England of Walleye confirms that “when you add that up, the investor gets about half of the return.”

But clients don’t complain as long as the returns are good enough, and Barclays data suggests they are. Over the past three years, pass-through funds have generated returns of 10.6%, compared with returns of 6.1% at funds employing traditional fee structures. Importantly, alpha is superior, too: 8.5% versus 4.0%. Although more expensive to extract, multi-manager funds are currently mining enough alpha to keep both managers and fundholders happy.

The catch

Life at a multi-manager fund may not be for everyone, though. The risk model that sits at the centre of these firms can be constraining. Porter Collins and Vinny Daniel spent some time at Citadel after leaving a traditional hedge fund firm, where they’d worked with Steve Eisman on The Big Short (Vinny is played by Jeremy Strong in the movie). “One of the things that really struck me was that it’s not investing,” said Porter on a recent podcast. “There's actually no part of investing to it. It's managing a bunch of tickers within a risk framework.”

The risk framework these firms deploy revolves around volatility. Portfolio managers are obliged to structure trades within what can be very narrow volatility rails. This impacts position sizing, portfolio turnover, investment time duration and a host of other factors that underpin portfolio construction. By the same token, it precludes some strategies such as contrarian investing “because contrarian takes time and their business models don't allow time or risk of loss,” says Vinny. And sometimes the framework can drive the investment process, requiring portfolio managers to gross up positions in periods of low volatility and de-gross in periods of high volatility, regardless of their fundamental views.

Dmitry Balyasny was late to implement the framework into his business but after losses in 2018, he hired the former head of global portfolio construction and risk from Citadel and began to embrace it. “When I joined and looked at things holistically,” says his new head of risk, “risk management was viewed as a loss mitigation technique, as opposed to being a backbone to an alpha-generation process.” By deploying a volatility target model, he reckons that risk management can become an alpha-generation tool rather than just a defensive measure.

The advantage of such a maniacal focus on volatility is that it allows higher leverage, another key feature of the model. At the end of March, Citadel had $339 billion of gross market exposure on net assets of $59 billion, equivalent to a 5.7x leverage ratio. At Millennium, the leverage ratio was 6.7x, having fluctuated between 5.5x and 6.9x at the end of each of the past seven years.

Such leverage ratios may actually understate the true picture because they don't reflect gearing inherent in derivatives structures or repurchase agreements. A similar calculation for Walleye reveals a 2.4x leverage ratio, yet CEO Will England says that “for us, it’s been 500% to 600% over the years, and that’s been reasonably stable.” A quarter of his book is in options.

As Vinny alludes, leverage constrains multi-manager firms’ investment strategies. Leverage nearly took down Citadel in 2008, when its main funds were down by around 50%, and so the firm has adapted. “Don’t pretend to be a bank,” advises Ken Griffin. “Post that moment in time, we’re in the moving business not the storage business,” he says. “So we’re looking for higher return on asset ideas, we’re looking for velocity of ideas in our portfolio; we’re not interested in…a more classic carry trade, like a bond basis trade that was a big part of our business back in 2007.”

The risk framework helps to keep volatility in check at the team level, but there is an additional mechanism a level further up. At Millennium, a 5% drawdown leads to the team having their risk cut in half; a 7.5% drawdown leads to a complete wind-down of the portfolio.

This leads to substantial staff turnover. In 2019, Millennium made 130 new hires, but let 50 people go. Portfolio manager turnover can be 15-20% per year (albeit 4-5% retire every year). As at the end of 2019, only 55% of Millennium’s portfolio managers had made it to their three year anniversary (although the firm might argue that churn in the traditional, single-manager hedge fund industry is higher).

Increasingly, there’s another feature of the multi-manager model that investment professionals may also baulk at. The team at the centre – what was Chicago in Citadel’s case, since moved to Miami – has a God’s-eye view over all the trades made by all the portfolio managers across the entire firm. With additional information about the portfolio managers’ strengths, weaknesses, behavioural tics and so on, they can replicate a subset of those trades in a centre book.

As Byrne Hobart describes, “the model is a very clever way to get more upside from work managers are already doing… In other words: adding a low marginal-cost, highly-scalable business line that amortizes existing operating expenses over more revenue is almost always a good decision.”

In some ways, it’s an evolution of the alpha capture systems that hedge funds began rolling out 20 years ago to harness the investment recommendations of sell-side brokers. That system’s pioneer was Marshall Wace, which launched TOPS – short for “trade-optimised portfolio system” – in 2002. Initially, it was used simply to track broker recommendations but the signal proved too good not to back it with real money. Although brokers themselves do not put money into the trades (“it’s like fantasy football for salespeople,” says one) they are remunerated via brokerage fees. The system has fuelled the growth of Marshall Wace into a $63 billion firm, making it marginally larger than both Citadel and Millennium.2

The overall margin of a centre book may not be as high – the cost of sourcing investment ideas at a 15-20% payout rate is higher than brokerage fees paid to brokers – but the incremental margin is higher since those ideas are already captive. And with talent leaving brokerage firms, centre books should be able to outperform traditional alpha capture systems.

What the systems have in common though is an ability to extract value from the behaviour of the portfolio manager. In his book, 10½ Lessons From Experience, Marshall Wace founder Paul Marshall charts the trades of a single contributor with a very high success ratio of 64%. To frame how good that is, Will England says that “you only need to be right 55% of the time” and that “the difference between 55% and 57% is huge.” The challenge Paul Marshall’s broker had was a “disposition bias” that prompted him to sell his winners and hold his losers – an issue that can be overcome at the centre. (He also writes that the reddest flags for underperformance are problems in people’s personal lives – the three Ds of death, divorce and disease.)3

The problem is that professional portfolio managers may not like it. Says Will England (emphasis added):

“If you're running x hundreds of millions of dollars in a given sector and half of that is the PM [Portfolio Manager] and they’re getting carry on that, and half of that is run by the centre team, and there’s no carry on that before it goes to the fund, then obviously, that’s more efficient for the fund, but it can also create tension.”

Byrne Hobart argues that this is just another step in the ongoing institutionalisation of asset management, with the centre book making the portfolio manager’s job closer to that of an analyst. For now, there are sufficient fees available to pay them well regardless, but over time their share of the economics may shrink, especially as their contribution can be more accurately measured at the same time as multi-manager firms accumulate scale. A similar shift happened on investment bank trading floors, with more of the value flowing to the firm rather than the trader.

The consequences

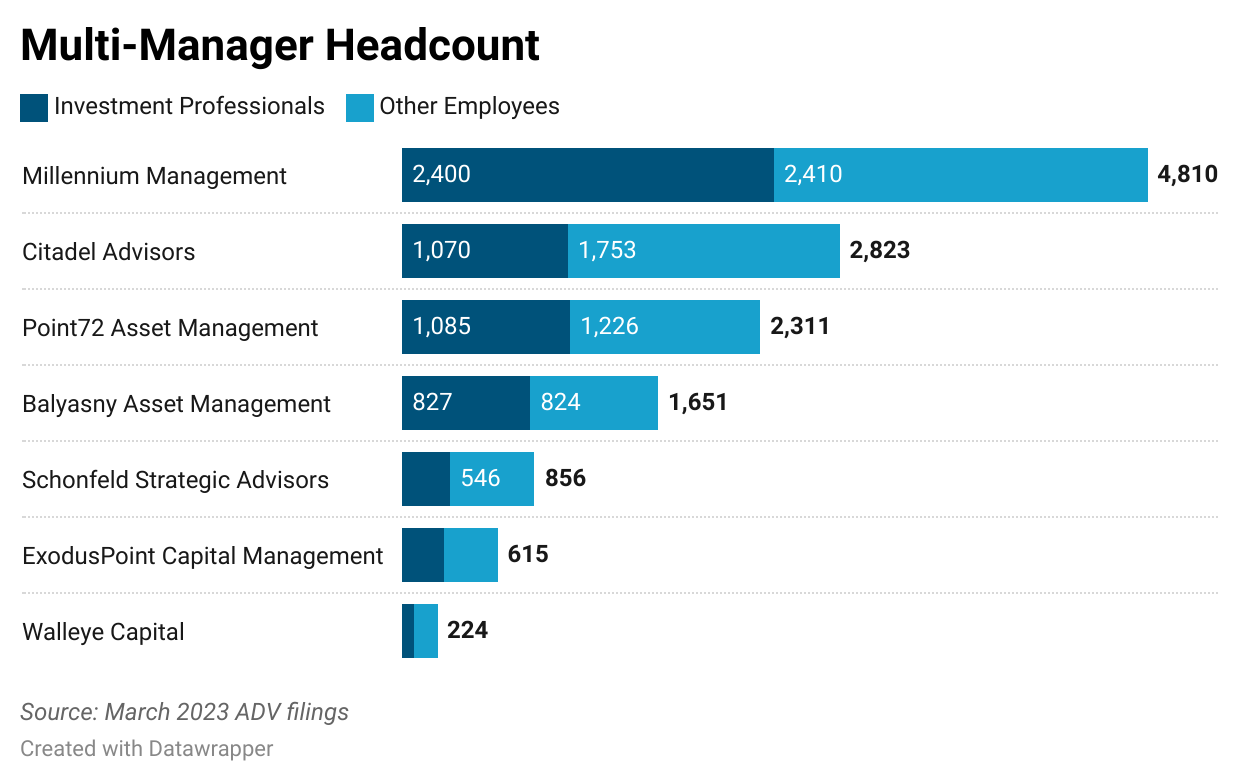

There’s no doubt multi-manager firms are here to stay and, as their models are very infrastructure heavy, they will tend towards larger scale. To compete, they need to run world-class technology, operations, legal, compliance and accounting systems. “The complexity doesn’t scale linearly, it scales exponentially,” says Will England. Already, the top four firms employ 11,600 people, including 5,400 investment professionals, based on recent regulatory filings.

For single managers, it presents a challenge. “You cannot beat the Citadel analysts,” says Porter Collins. “There’s 50 of them all looking at the same name and back book behind it. It’s hard to beat that.”

The one factor conspiring against multi-managers, though, is that they may ultimately run out of capacity, particularly given the volatility constraints that prevent them from fishing in the whole pond. In addition to the limit on available talent highlighted by Will England, they may also be limited by market impact. At the beginning of 2020, Millennium was doing around 2% of all the equity trades in the world; Bobby Jain reckoned that could get to 5% without impact. The firm is now 40% bigger so it’s still not there yet, but it’s getting closer.

As a solution, multi-manager firms are beginning to allocate to external managers. According to Barclays, some 40% of firms are now allocating at least some capital to outside managers. Balyasny’s client documentation explains that the rationale is to provide “access to certain markets and…strategies not otherwise deployed by the Investment Adviser and/or other opportunities.” The firm estimates that fees and expenses paid externally will be similar to those for internal portfolio managers, but advance draws on performance fees will be made available for external managers.

For now, multi-manager firms will continue to soak up assets. Multi-strategy funds (a broader definition of fund than multi-manager) picked up inflows of $29 billion over 2021 and 2022 at a time when hedge funds overall suffered outflows of $98 billion. In the year to July 2023, they have collectively gained a further $1.8 billion, with the broader industry losing $43 billion, according to eVestment.4

But rather than take over the entire industry, their role may morph into gatekeeper as they oversee the industrialisation of alpha. Bobby Jain may not make it into a future edition of Market Wizards, but he could yet make it into a book about business leaders.

Lots of resources linked throughout but I would especially highlight the interview Porter and Vinny did with Ted Seides; the interview Will England did with Patrick O’Shaughnessy; a Financial Times Big Read; and an FT Alphaville follow-up. For practitioners in the industry, former Citadel portfolio manager Brett Caughran lays out a very good seven-point strategy for single managers to “beat the pods”.

If you like the article, please ♡ or better still, refer a friend.

Ken Griffin argues that his model is actually a bit different in that his teams don’t compete with one another – tech portfolio managers across the firm, for example, share ideas and compare notes. He contrasts it with other firms that run completely stand-alone teams. “They literally think about things like, what if we have two managers that cover tech in the same elevator at the same time? Are they going to start to have more correlated trading?”

The story goes that TOPS was born out of a bet between Paul Marshall and Ian Wace, the founders of Marshall Wace. Marshall, former head of Mercury Asset Management’s pan-European equity business, thought that the investment calls made by stockbrokers were worthless. Wace, former global head of equity and derivatives trading at Deutsche Morgan Grenfell, maintained that the banks wouldn’t pay for research if it didn’t have value. They decided to settle the debate by designing a system to measure the outcome of sell-side calls.

One benefit of the broker model, according to Paul Marshall, is that its “fantasy” nature can make it quicker to adapt to events. “TOPS contributors…were quicker to adjust their positions than our in-house managers,” he writes in his book. “With a virtual portfolio you can switch on a dime. This is what happened in March/April 2020, and our Market Neutral TOPS hedge fund enjoyed the best trading month in its history in April.”

Multi-strategy funds are a broader category of fund that multi-manager funds. Most multi-manager funds operate multiple strategies – long/short equity, volatility trading, fixed income macro and so on. WallEye is 25-30% volatility trading, 40% long/short equity and 30-35% capital market strategies and fixed-income macro, according to CEO Will England. But single managers can also operate a multi-strategy approach, e.g. Sculptor. The data from eVestment covers $670 billion of multi-strategy funds; according to Barclays, the multi-manager subset account for around $300 billion of assets.

Fascinating. I’d love to see and understand Excel model that supports expense numbers. What’s left for investors net of fees, incentives, costs and taxes??? Guess - Not much.