Inside the Affordability Crisis

The Mortgage Infrastructure Underpinning American Housing

Happy Friday. I was back on the Macro Hive podcast this week, talking to host Bilal Hafeez about a range of things we’ve addressed in the newsletter over the past few months: AI bubbles past and present, the 1907 crisis and the rise of non-banks, private credit risks, fraud cycles, Jane Street’s technological edge, blockchain’s slow creep into banking, and what AI means for entry-level finance jobs. We also touched on two books I’m reading: 1929 and The Land Trap. The episode is available on all the usual platforms.

I’m also hosting a webinar on December 4th about the private credit marketplace, sponsored by AlphaSense. Details further down, or you can sign up here. For now, though, back to the newsletter...

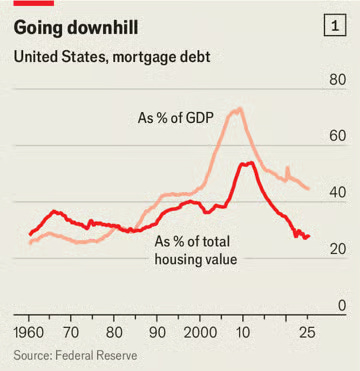

For all the talk of bubbles in equity markets, private credit and elsewhere, the market that hosted the last great bubble has been quiet. It’s still vast: At roughly $13.5 trillion, more mortgage loans are outstanding than corporate bonds in the US. But its footprint has been shrinking. As The Economist notes this week, mortgage balances have fallen by almost 30 percentage points relative to the size of the economy since the peak of the last boom, taking them back to late-1990s levels. Set against the value of American homes, the decline looks even starker: mortgage debt now amounts to barely a quarter of household real-estate wealth, the lowest share in more than six decades.

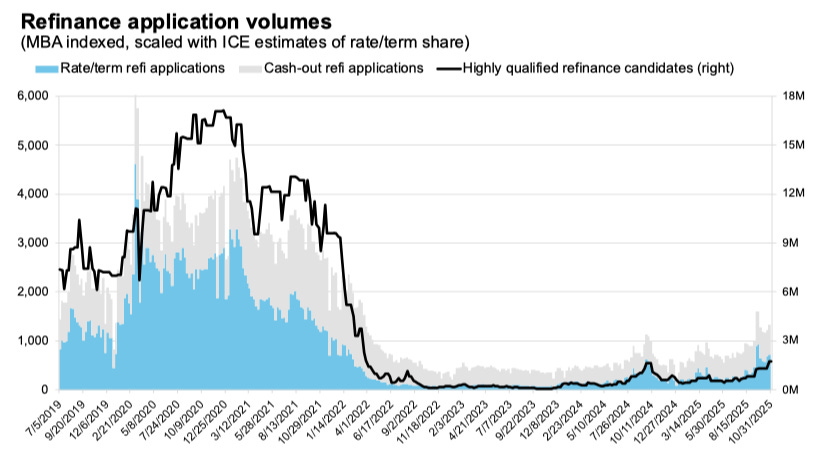

For mortgage bankers, this didn’t initially pose much of a problem. As long as interest rates were drifting lower, they could rely on a steady stream of refinancing. Every decline in rates invited borrowers to reshuffle their loans, creating new mortgages even when nothing new was being financed. It was flow without growth – and for years it kept the business humming. When rates fell to almost unimaginable lows in 2021 – touching 2.65% on a 30 year fixed-rate mortgage – originations swelled to $4.4 trillion, more than twice their usual level, handing a windfall to the bankers who sat in the middle.

But with rates now above 6%, those days are long gone, and refinancing activity has collapsed. Intercontinental Exchange, owner of a mortgage technology platform, estimates that at current rates, there are 1.7 million borrowers out there with capacity to refinance. That’s up from a few years ago, but it’s way down on the 17 million borrowers whose mortgages became refinanceable when rates began their descent. Most borrowers are already on rates below 6%; many boast rates below 4%.

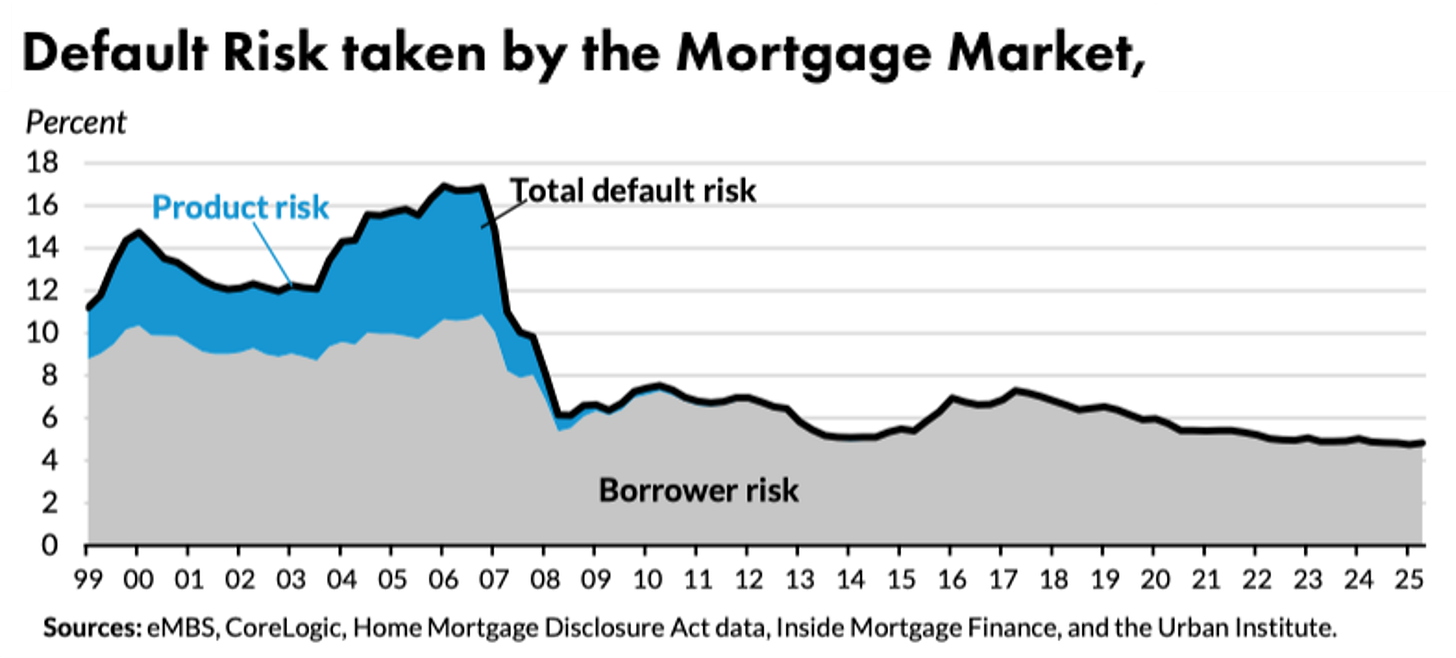

That leaves the purchase market as the primary source of new mortgage activity. Trouble is, those investors who assume the ultimate risk of mortgage default don’t want to take on much more. Unlike peers in other markets, their tolerance for absorbing loss is exceptionally low. The Urban Institute’s Housing Credit Availability Index sits at an all-time trough. Such risk aversion is also reflected in credit scores. In 2003 35% of mortgages went to borrowers with credit scores below 720; currently, the proportion is only 22%. Denial rates in the purchase segment hover around 10%.

Even when a mortgage application is accepted, the cost can be high. Although some of that is driven by investor demands, tighter regulation also pays a part. “I’ve been talking about it for years,” said JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon in October. “They should focus on reducing securitization requirements, origination requirements, servicing requirements, and we think you can reduce the cost of mortgages 30 or 40 basis points overall, without creating any additional risk. They’re just excessive stuff put in place after the Great Financial Crisis, which obviously demanded a response, but it’s excessive.”

There’s been a lot of discussion recently about affordability and a tighter mortgage market feeds into that. When home prices were rising and mortgage rates were falling, the market cleared. With high home prices and high mortgage rates, it ceases to function for segments of the population. The American 30-year fixed-rate fully prepayable mortgage is a curious product, but although an entire apparatus exists to ensure its liquidity, it doesn’t help liquidity in the underlying housing market when borrowers face 70%+ increases in mortgage payments if they move. No wonder the median homebuyer age today is nearly 60, and a first-time home buyer is now 40, according to the National Association of Realtors.

“In terms of mortgages and home lending, no secret, that has been a headwind to our loan growth as we continue to see paydowns on our portfolios,” said JPMorgan at a recent investor presentation. “And as a result, we expect to continue to see slow declines in our home lending portfolios.”

Affordability clearly has wider economic implications, but where does it leave the mortgage industry? To explore the issue through the lens of mortgage originator Rocket and mortgage guarantor Fannie Mae, read on.