Bubble Trouble

AI, Capex and the Anatomy of a Bubble

“How do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions…?” — Alan Greenspan, December 5, 1996

If you’ve been signed up to Net Interest for a while, you will have read me reminisce about the bursting of the dot-com and telco bubble in 2000. It was one of several boom-and-bust cycles I saw up close as an analyst and investor. I entered the industry too late to catch the Japanese stock bubble and I am too young to remember historic classics such as the Nifty Fifty (1973), but the tech crash, the housing collapse and the Chinese stock bubble all left their mark.

So it’s with a sense of foreboding that I note the rising number of voices drawing parallels between 2000 and today. “You’re going to see a similar phenomenon here,” Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon told delegates at Italian Tech Week earlier this month. “I wouldn’t be surprised if, in the next 12 to 24 months, we see a drawdown with respect to equity markets… I think that there will be a lot of capital that’s deployed that will turn out to not deliver returns, and when that happens, people won’t feel good.” At the same event, Jeff Bezos characterized the current environment as “kind of an industrial bubble.” Even AI insiders are expressing caution. “I do think some investors are likely to lose a lot of money,” said Sam Altman.

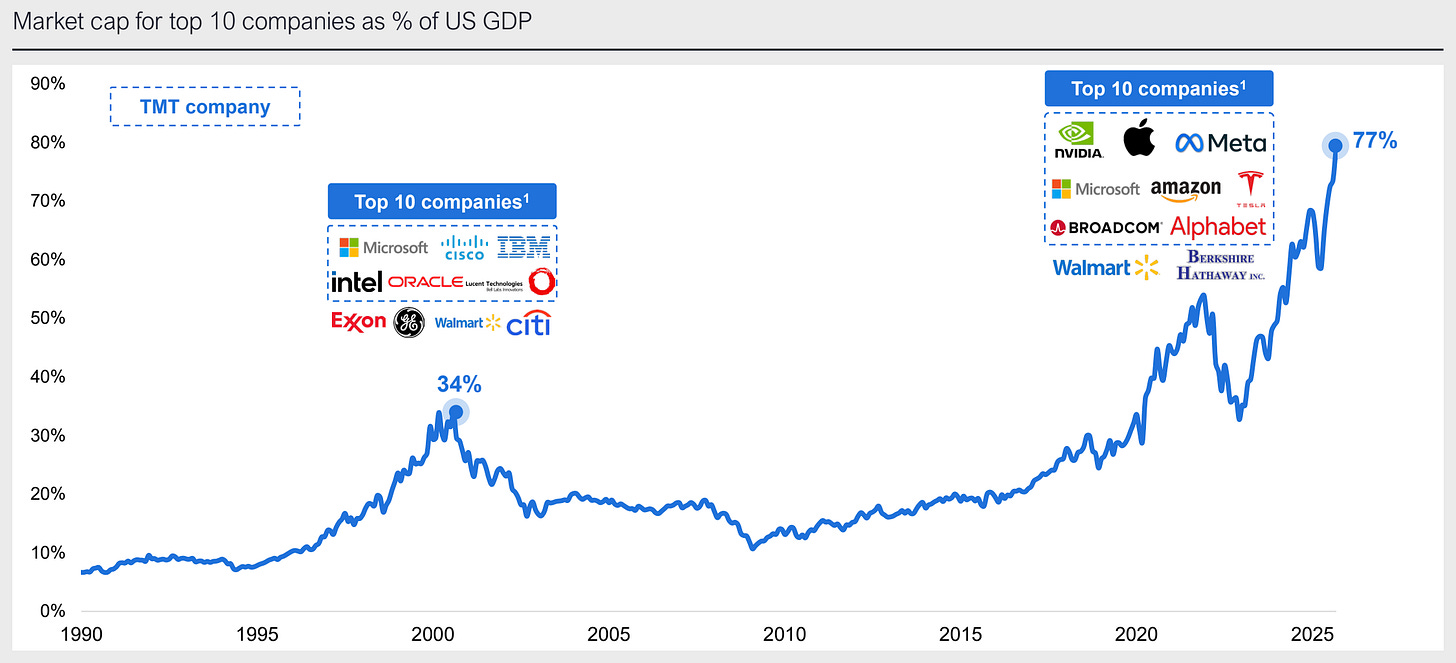

Since these remarks were made, Nvidia’s market value has risen past $5 trillion. In aggregate, AI-related stocks account for about 75% of S&P 500 returns, 80% of earnings growth and 90% of capital spending growth since ChatGPT launched in November 2022. The five largest US technology companies are now worth more than the combined markets of the Euro Stoxx 50, the UK, India, Japan and Canada; the ten largest US stocks account for nearly a quarter of global equity. It is understandable that people are asking whether we are in a bubble.

My former colleague Andrew Garthwaite, UBS’s chief global equity strategist, argues that the preconditions for a bubble are certainly in place. He highlights seven factors that typically underpin bubbles:

A pervasive “buy‑the‑dip” mentality. This tends to emerge when equities beat bonds by more than 5% a year for a decade; over the past ten years, equities have outperformed by around 14% a year.

A “this time is different” consensus tied to a major new technology. This comports with a 2018 study which found that in a sample of 51 major innovations introduced between 1825 and 2000, bubbles in equity prices emerged in 73% of the cases.

A roughly 25‑year gap since the prior bubble, allowing a new (untainted) investor cohort to emerge.

Retail buying – a theme we’ve discussed here before. Roughly 21% of US households now own individual stocks (33% including funds) with overall equity ownership having regained all ground lost since the dot-com crash. And to echo the first point, retail loves to buy the dip: Individual investors successfully bought stocks all the way through the April market correction.

Profit pressure in the broader market. In the late‑1990s boom, national accounts profits peaked in 1997; in Japan, trailing earnings per share growth was flat in 1989, even as it was flattered by corporate stock trading. Today, outside the top ten companies in the US, 12‑month forward earnings per share growth is close to zero.

Loose monetary conditions, reinforced by this week’s rate cut, lowering discount rates and supporting risk appetite.

While Garthwaite’s framework supports the notion that a bubble is inflating, it doesn’t map its contours. To do that, we need to dig deeper.