October Throwbacks

When Shadow Banking Meets Systemic Risk: Lessons from 1907

It’s the anniversary of Black Thursday today – the day in October 1929 when the market plunged 11% at the open before falling by a third over the next three weeks. Already etched into Wall Street folklore, events of that day have attracted renewed interest with the release of Andrew Ross Sorkin’s latest book, 1929.

Sorkin describes the scene:

[Exchange superintendent William] Crawford watched the chronometer tick. At exactly 10 a.m. he punched the bell to signal the opening of trading. Men began yelling and gesticulating. Phones started ringing incessantly. The bloodbath had begun… At first the sell-off was driven by brokers liquidating the accounts of customers who couldn’t meet their margin calls. But the panic soon became so pervasive that brokers were willing to sell at any price. Brokers, still behind from processing the previous night’s paperwork, struggled to keep up… By the time it ended, the turmoil of Thursday, October 24, broke records. It was the heaviest trading day in the history of the New York Stock Exchange, with brokers handling transactions of 974 different stocks, with 12,894,650 shares changing hands. The stock ticker recorded the day’s final trades at 7:08 p.m., more than four hours late.1

Sorkin doesn’t address it in his book but on his podcast tour, he’s consistently asked whether he sees parallels between the conditions that led to the crash and today’s markets. On the All-In Podcast, he characterizes Radio Corporation of America (RCA) – whose stock price rose 200-fold during the 1920s – as the Nvidia of its time. He compares how wealthy financiers gained celebrity through magazine covers then, much as they command attention through social media today. Underlying it all, he observes, speculation remains the twin of innovation. “I think there’s probably some things that are happening in our economy today that do mirror that period,” he says.

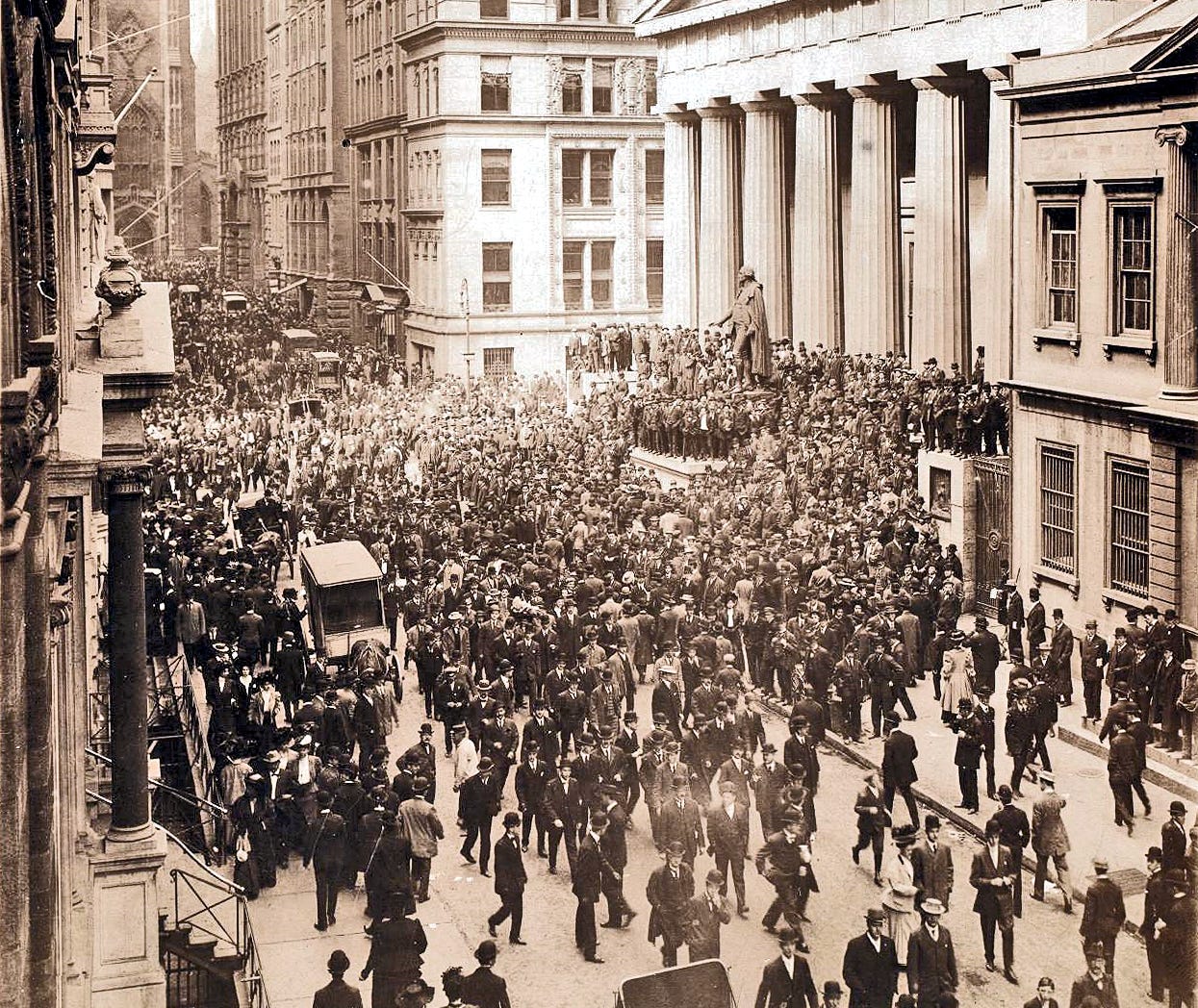

Such pattern-matching is deeply human – we instinctively search history for roadmaps to the future. Yet while there are echoes of 1929 in today’s markets, especially around retail participation in the market, it’s another historical episode that may offer even more relevant parallels. The Panic of 1907, where shadow banking created systemic vulnerabilities, captures crucial features of our current financial system that the 1929 crash doesn’t illuminate. It, too, marks its anniversary this week.

In their book, The Panic of 1907, Robert Bruner and Sean Carr describe events:

On Tuesday morning, October 22, the mid-autumn weather in New York City was fair and mild. That was fortunate since there was already an eddying crowd outside the Knickerbocker Trust Company’s great bronze doors at Fifth Avenue and Thirty-fourth Street by 9 a.m. Altogether about 100 people, mostly small shopkeepers, mechanics, and clerks, waited patiently on the sidewalk to reclaim their deposits. Even when the firm opened at its regular time an hour later, everything remained orderly and there were no violent scenes, tears, or frantic hand-wringing. Men stood in one primary line and women stepped into a separate room to the left of the bank’s main entrance. Within 15 minutes, the line extended out the doors and down the steps to the sidewalk, as company officers and policemen marshaled the growing crowd into formation.

Knickerbocker Trust was one of a new wave of shadow banks that had emerged since the 1880s. Less regulated than traditional banks, trust companies could assume more risk and take advantage of opportunities not available to banks. They grew explosively: while their lending amounted to just half that of New York’s national banks in 1890, by 1906 they had achieved parity. With few payment services to manage, they maintained minimal cash reserves and remained outside the protective umbrella of the New York Clearing House, a precursor to the Federal Reserve.

Trust companies no longer enjoy the same status, but their legacy survives in other forms. When the global Financial Stability Board last surveyed non-bank financial intermediaries, they put their share of total global financial assets at 49.1%, up from 43.1% in 2008. As in 1906, what goes on in this corner of the market is often opaque yet it is increasingly supported by bank lending and inter-relationships between the various institutions.

“Yes, there will be additional risk in that category that we will see when we have a downturn,” said JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon on his earnings call last week. “I expect it to be a little bit worse than other people expect it to be, because we don’t know all the underwriting standards that all these people did… I would suspect that some of those standards may not be as good as you think.”

Knickerbocker Trust didn’t survive that day in October, but its demise would reveal vulnerabilities in the financial system that resonate today. To explore how the crisis unfolded and what it tells us about current market risks, read on.