Bubble Trouble 2

GPUs: The Newest Asset Class

“In the marketplace there’s all kinds of incentives right now, and rightfully so. What do you expect an independent lab that is sort of trying to raise money to do? They have to put some numbers out there such that they can actually go raise money so that they can pay their bills for compute and what have you.” — Satya Nadella, CEO, Microsoft, November 2025

A few weeks ago, we harked back to 1907 to hunt down a blueprint for what is going on in markets today. The following week, we looked at 2000. This week, we turn our attention to 2008.

This isn’t something I set out to do. As much as there are clear differences between the current environment and that of 1999/2000, the differences with 2007/2008 are even more stark. Yet over the past few months, I’ve watched as a new asset class has emerged. Back in 2023, neocloud company CoreWeave raised a $2.3 billion debt facility collateralized by Nvidia AI chips. It has since gone public, raising a further $14 billion in debt and equity this year alone. Alongside it, other companies have issued debt similarly backed by AI chips (GPUs) and data center infrastructure. AI-related companies have collectively issued around $170 billion of US-dollar denominated credit so far this year according to Goldman Sachs – more than the prior three years combined and, based on their diminishing cash ratios, will continue to tap debt markets for capital.

But just as the financing model of 2007 hinged on a standardised set of assumptions around home price inflation, the current model rests on assumptions around the useful life of those chips – assumptions that are currently being challenged. CoreWeave estimates a six-year useful life for its computing equipment; other borrowers project less. The difference between six years and four years on a depreciation schedule underpinning a piece of GPU collateral is not far off the difference between +2% and zero home price inflation on a piece of housing collateral.

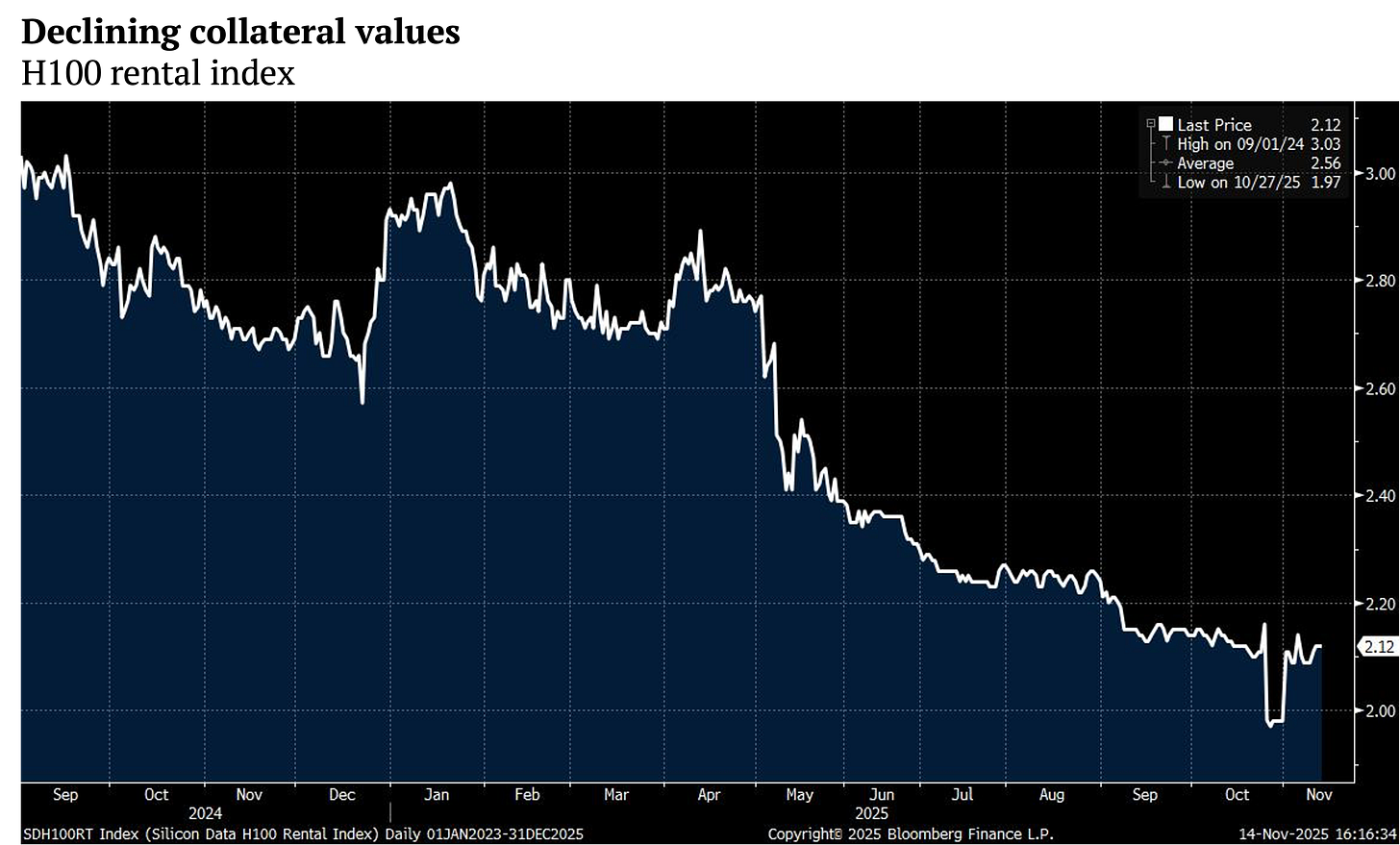

And just as the launch of the ABX subprime index in January 2006 put a spotlight on a previously opaque part of the market – and was in many ways the coordination point for the unwind that then unfolded – the Silicon Data H100 Rental Index, launched in May 2025, adds transparency to the compute market by tracking the hourly cost of renting a GPU. The goal, according to its founder, is to turn GPUs into a benchmarked asset class that can be traded like any other financial instrument. Reflecting evolving supply–demand dynamics in the GPU rental market, the index has been trading down:

There’s one more thing that strikes me as resonant of the 2008 period: attacks on short-sellers. Short-selling is a topic we’ve explored here before. As long ago as 1917, financier Bernard Baruch made the case for it: “A market without bears would be like a nation without a free press. There would be no one to criticise and restrain the false optimism that always leads to disaster.”

Since then, short-sellers have faced regular waves of vilification. In 2008, Morgan Stanley CEO John Mack accused them of “destroying a storied franchise, built over almost three-quarters of a century of hard work and integrity.” While short-sellers have been under pressure since 2021 (perhaps, to Baruch’s analogy, not uncorrelated to pressure faced by the free press) the current round of abuse seems strangely disproportionate. “I’m currently in a battle with short-sellers,” Palantir CEO Alex Karp said at the start of an interview this week. “Primarily because they could go short some carcinogenic company but they have to short arguably the best company in this country and in the world by any metric. And by the way, judge us by our enemies… What should our market cap be based on that standard?”

It came a couple of weeks after OpenAI CEO Sam Altman expressed a desire to enter the battle himself. Asked how he can reconcile $13 billion of annualised revenue – the rate in July, which is expected to rise to $20 billion by year end – with $1.4 trillion of spending commitments, he offered to find a buyer for the interviewer’s shares. “There are not many times that I want to be a public company,” he said, but one of the rare times it’s appealing is when there are critics. “I would love to tell them they could just short the stock and I would love to see them get burned on that.”

To dig more into this theme and to see which market indicators I’m most focused on right now, read on.