In the week King Charles III took the throne in the United Kingdom, I thought it would be fun to write about another king of his domain, also named Charles – Charles Schwab. It’s contrived, of course – the two have very little in common. They are broadly of the same generation (Schwab is 11 years older) and have their name and face branded on their institutions’ marketing materials. Schwab also got a bit of family help to get started, although not as much as his namesake.1 But that’s where the similarities end. In particular, while one has delighted the crowds these past few weeks, the other, not so much.

This piece is divided into two sections. The first, free to read, explores the history of Charles Schwab; the second, available to paid subscribers, addresses the challenges the company currently faces. If you’d like to sign up as a paid subscriber, please do so here:

Charles Schwab: The Broker

Before he disrupted the brokerage market, Chuck Schwab was a newsletter writer. In partnership with a former colleague and a financial backer he set up a business distributing a biweekly newsletter, Investment Indicators. At peak, the letter had 3,000 subscribers paying $72 a year (good – although not enough to make it onto the Substack leaderboard). Alongside his writing, Schwab launched a mutual fund and venture capital arm, but struggled to achieve success. He bought out his partners, renamed the firm Charles Schwab & Company – Schwab was already taken by a Hollywood drugstore – and cast around for new ideas.

We’ve talked before about how financial innovation often happens in the embrace of regulation. In May 1975, the US Securities and Exchange Commission was due to deregulate brokerage commissions. Up until then, trading fees were fixed; afterwards, brokers would be free to set their own rates. Schwab thought there was room to go in cheap. Most brokers – Merrill Lynch the prime example – offered a full relationship service. By stripping away “the fluff”, Chuck Schwab calculated that he could cut prices by 75% and still make a profit.

It was textbook disruptive innovation: an entirely new market created through the introduction of a new kind of product or service, one that’s actually worse, initially, as judged by the performance metrics that mainstream customers value. When Merrill Lynch raised its prices on lower ticket trades in response to deregulation, Schwab had an opening. He reckoned there were other independent investors around like him, who wanted to trade stocks on the back of their own research and didn’t need the full range of services provided by traditional firms. He guessed his addressable market was perhaps 10% of the investing public.

Leaning on his experience as a newsletter writer, he understood the power of direct marketing and used a similar model to grow his firm. Rather than push individual stocks like other brokers, he would market his discount brokerage service broadly and follow up with sound customer service. As the business grew, customer numbers themselves were used as a marketing device (another technique employed by newsletter writers – 65,000 subscribers can’t be wrong).2

Transaction volumes started slow at 20 or 30 trades a day, then increased to 100 and rose from there. Along the way, Schwab encountered many challenges, chief among them aligning operational resources with customer demand. In his memoir, Invested: How Charles Schwab & Company Revolutionized Investing, Schwab uses a two-line chart to illustrate the point. One line is more or less straight, rising all the time: that’s the cost structure. The other is rising, too, but in a much more volatile fashion: that’s trading volume. When you go from averaging 300 trades a day to 800 within six months, you’re going to have problems.

“Our customer service was still not where it needed to be, our record-keeping was full of holes, government regulators were bearing down on us, and our workload was insane.”

In order to raise capital to invest in the business, Schwab looked to IPO. By 1980, discount brokers – of which Schwab was the largest – controlled around 8% of the market. But the valuation placed on the business was not very high and Chuck pulled the deal. Instead, he sold 20% of the company for $4 million to National Steel.

The National Steel capital injection provided some relief, but the pressure for cash mounted. A year later, Schwab got an offer he couldn’t refuse: Bank of America wanted to buy the whole business. In 1982, less than a decade into its existence, Schwab sold to Bank of America for $52 million in stock. With profits at $5.2 million and customer growth of 85% it looked like a steal. Chuck Schwab became Bank of America’s largest individual shareholder with a stake of $20 million, joining its board.

Unfortunately, the marriage didn’t work. Bank of America ran into problems of its own in its lending portfolio. According to Chuck, “Every original plus of being associated with Bank of America was now a minus: instead of providing us with capital, BofA was telling us we had to cut our budgets; instead of giving us a platform to enter new markets and offer new products, it was blocking our every move; instead of buffing our reputation, it was tainting it.”

In 1986, Schwab bought the company back in one of the first leveraged buyouts structured around cash flow rather than hard assets. Because he retained the rights to his name and image, no other bidder could make a credible offer without Chuck’s blessing, so the field was all his. He borrowed $255 million and raised $25 million in equity, putting in almost $10 million of his own money. Strong performance at Schwab took the ultimate consideration to $330 million, but at 11 times 1986 earnings, it was a good deal.3

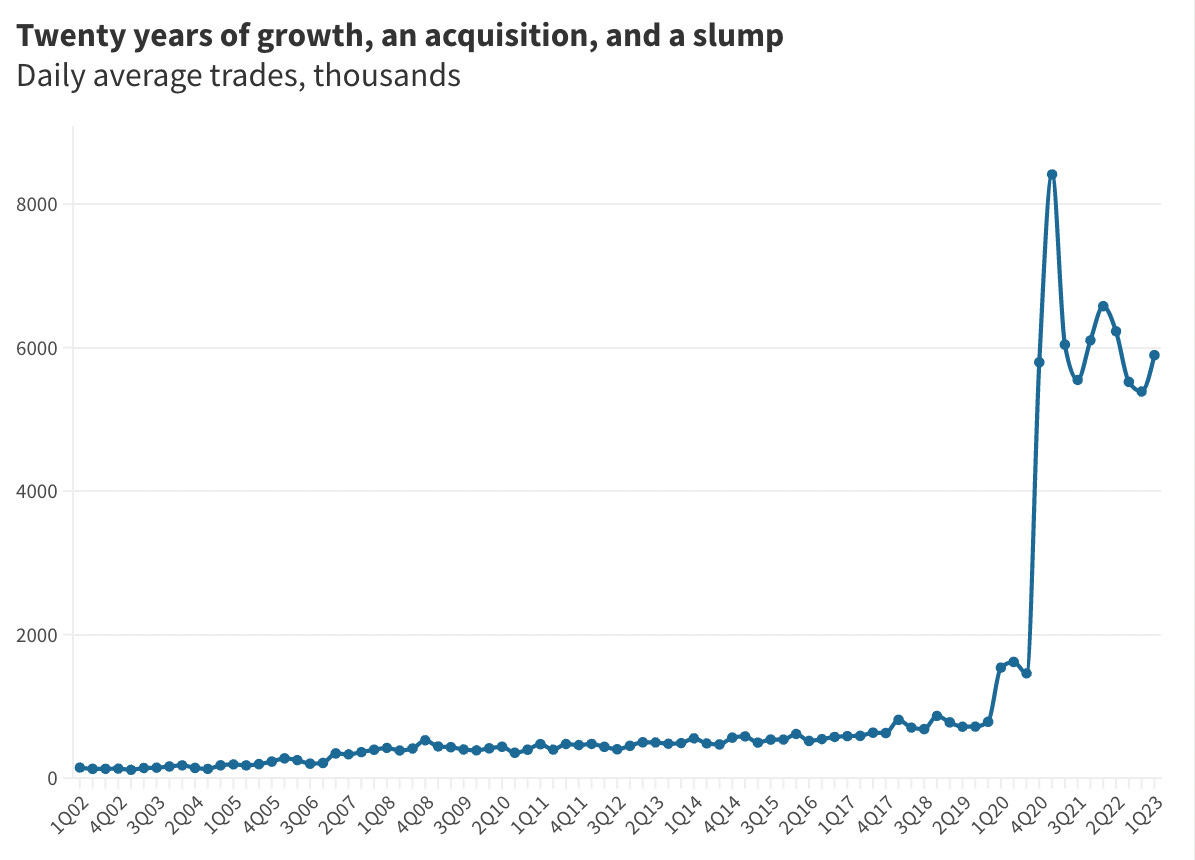

Within a year, Chuck IPO’d the company, listing it a matter of weeks before the Black Monday crash of 1987. The timing was fortuitous, allowing Schwab to deleverage its balance sheet before the market turned. The months before the crash, the company was doing around 17,000 trades a day; the subsequent lull in the market meant it would take until 1991 to do those volumes again.

The 1990s were a good time for Schwab. The firm diversified into other areas. It launched a mutual fund marketplace, developed an independent financial adviser network and introduced a no-fee retirement account.

It also adapted to the internet. Schwab had launched an online platform back in 1984, so was ready when internet trading took off. Management made a key decision in 1997 to integrate online and offline at the same (lower) price point, at the expense of short-term revenues. “The strategy team estimated a year-one hit to revenue in the hundreds of millions. We just had to be confident that while it was not going to be profitable in the short run, it would be profitable in the long run.”

Cheaper trading meant more trading and with dotcom mania in full flow in the years that followed, trading volumes rose – from 65,000 a day in 1997, to 100,000 in 1998, to a high of 350,000 in 2000. But then the market turned. Which might have been fine, but it took Schwab a while to realise it. On an earnings call in 2001, Chuck admitted, “We’ve come through a highly speculative technology bubble. Maybe I should have been more emphatic about understanding that this was a temporary phenomenon.” Trading activity sagged to 200,000 “which shocked us until it dipped below 150,000, then 100,000.”

Since that low point, Schwab has continued to grow. Pricing has fallen but volumes and scale efficiencies have compensated. In October 2020, Schwab merged with TD Ameritrade to add to its scale – full account transition is slated for later this year.

But the growth isn’t without its challenges. In his memoir, Chuck Schwab talks about “a basic, hard truth” – that “rising interest rates are the stock market’s enemy.” He explains that “for brokers…rising rates translate into a deadly combination of falling revenues and rising expenses.” As a hedge, the group diversified into banking, which should benefit from rising rates. Unfortunately, that banking business is now the source of challenges.

Paying subscribers, read on…