Rising Beta

Plus: Beal Bank, Sculptor

A guest post this week from two investors who, like me, have spent their careers looking at banks and financial services companies. Allen Puwalski and Robert Lacoursiere worked together at Paulson & Co., the firm famous for “The Greatest Trade Ever”. They recently reunited to found Cybiont Capital, where they apply a systematic approach to bank research and investing. Here they discuss their outlook for net interest income at US banks. For paid subscribers, a few comments follow from me on Beal Bank and Sculptor Capital Management.

For all the diversification that has taken place in the banking industry over the years, net interest income remains its life blood. Excluding the large money center banks, about 70% of industry earnings in the last 12 months came from net interest income.

Yet the outlook for this revenue line looks challenging. Having benefited from rising rates over the past year – when net interest income rose 4% on average – banks now have to contend with the aftershocks of one of the most unusual interest rate cycles on record. The fate of Silicon Valley Bank highlights an extreme case of a bank unable to manage the transition from a sustained period of low rates to a period of higher rates, but others are also struggling.1

Some of the pain is self-inflicted. Many banks failed to manage their funding agility ahead of last year’s rate hikes, hamstringing themselves by deploying excess liquidity at historically low rates. Many capitulated at just the wrong time and in the worst possible way by buying massive amounts of fixed-rate mortgage-backed securities (MBS). These securities have a pernicious characteristic called negative convexity, which causes their weighted average lives to extend when rates rise and their value to decline. Liquid assets that should have been available to fund the exodus of deposits searching for higher yields instead became entombed on balance sheets because selling them at their reduced value would result in immediate and significant earnings and capital damage for many banks.

Those banks with sufficient capital have the option to take a one-time hit to restructure their securities book for the sake of future earnings. This bodes well for them because analysts and investors have a tendency to view such a hit more favorably than earnings stagnation that would otherwise play out over the roughly 8-year life of the MBS.

But because many banks are capital constrained, they can’t touch these securities. Doing so would force them to recognize in regulatory capital unrealized losses that are currently ignored. As a result, these banks are forced to seek out higher-cost funding sources.

Consider the example of Zions Bank.

Zions is a $5 billion market cap regional bank. It didn’t fail, nor did it garner much attention through the 1Q23 banks scare. Zions held out until 4Q20 before beginning an accelerated MBS buying spree in which it grew its MBS book from 6% to 23% per quarter through year-end 2021. Then the Fed’s rate increases began. By 3Q22, Zions had unrealized securities losses amounting to nearly $3 billion or nearly 40% of its tangible common equity. The following quarter, the company started reporting significant interest expense from higher cost Federal Home Loan Bank borrowings. In the next quarter, in an attempted sleight of hand, they changed their definition of tangible common equity to exclude securities losses and moved almost $10 billion of securities to “held-to-maturity” (HTM) where further declines in value would no longer result in additional equity consequences but also where none of the securities could be sold without the risk of needing to mark to market the entire HTM book through both equity and earnings (“tainting the book” in accounting parlance).

By year-end 2022, Zion’s tangible common equity ratio (conventionally calculated) had fallen to just over 3% of tangible assets despite it reporting a common equity tier 1 ratio (CET1 ratio, the primary regulatory target) of 10.5% of risk-weighted assets. The majority of the delta between the two ratios resulted from unrealized losses on its available for sale (AFS) securities portfolio, which are currently excluded when calculating regulatory ratios.

Selling its mortgage-backed securities book would have resulted in a highly visible hit to regulatory equity. Instead of selling securities, the bank raised funding via borrowings, paying over 7.5% on $8 billion of borrowed funds while earning a sub-2% yield on its untouchable HTM securities book. That’s a $440 million annual hit to net interest income.2

One way to measure the risk to net interest income at banks like Zions is through an analysis of funding cost “beta”, defined as the change in a bank’s funding rates compared to the change in market rates.3

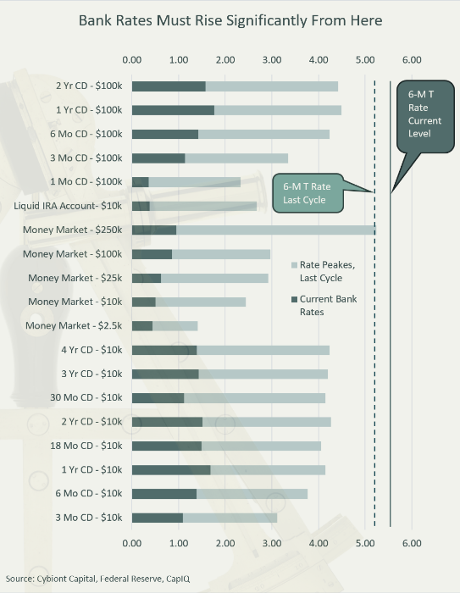

The chart below compares average deposit rates at last cycle’s funding-cost peak (which occurred two quarters following the peak in the effective Fed Funds rate during 1Q07; light bars), to current average bank rates (dark bars). The 6-month Treasury rates are shown for reference. The current 6-month Treasury rate sits 34 basis points over the peak in the the last cycle. At present, bank rates aren’t anywhere near where they were the last time rates were this high, and they aren’t competitive either to money market rates or rates being offered by rapidly growing fintech alternatives. As we’ve described, banks have met at least some of their funding needs with other borrowings and have resisted the optics of raising deposit rates. That can’t last.4

During the last rate hiking cycle (from June 2004 to June 2006), the Fed Funds rate peaked at around 5.25% and stayed near that level only for about a year before declining rapidly into the global financial crisis (GFC). In the current cycle, rates are already near their terminal level and got there much more quickly. Two additional potential high-probability outcomes differentiate this from the previous cycle: either rates will remain near current levels for an extended period of time as the Fed tries to quell inflation without causing a recession, or rates will fall sooner only because we enter a recession.

Though for different reasons, neither of these outcomes is bullish for commercial banks. Either funding costs will rise significantly over a lengthened beta measurement period without a concomitant increase in asset yields, or credit quality will deteriorate because the Fed fails to deliver a soft landing.

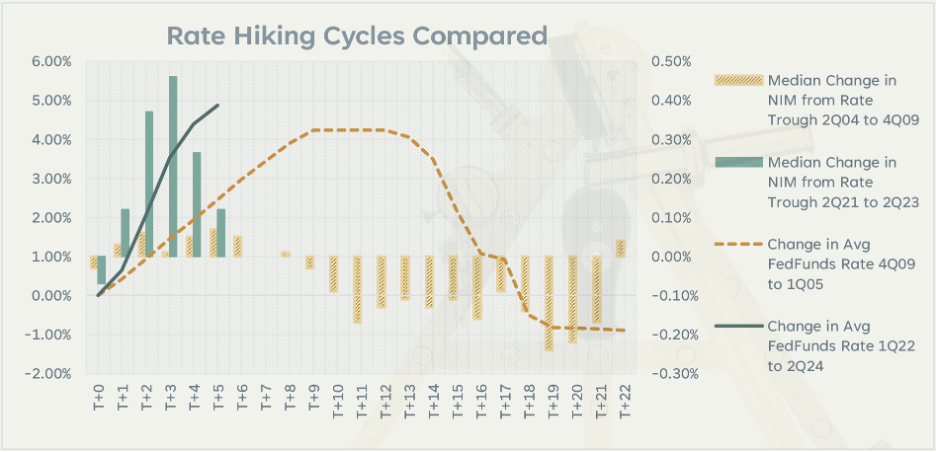

Consider the next chart comparing changes in bank net interest margins relative to the change in the Fed Funds rate from the last rate hiking cycle to the current one. We saw during the last rate cycle that margins improved initially; but that once rates stabilized, net interest margins eroded markedly as bank funding rates crept up faster than asset yields and banks entered an extended period of compressed margins. Although market rates were sustained at high levels for only about a year, the median funding cost beta for banks reached almost 40% before funding costs began to decline with the Fed Funds rate. The beta for earning asset yield peaked at 38% in the last rate cycle.

When we consider our current rate hiking cycle, we see a marked initial improvement in bank net interest margins due to the front-loading of benefits. These improvements came fast, with bank asset yields moving up far more quickly this cycle because of significantly higher proportion of floating rate loans on banks’ balance sheets and because banks were flush with excess liquidity accumulated during the pandemic, much of which has since runoff.

These benefits appear already to be all but spent, and we see the trend toward compressing net interest margins developing at a much faster pace than during the last rate cycle. We believe from here that earning asset yields will plateau quickly as the Fed halts further rate increases; but that the cost to fund earnings assets will accelerate higher as rates remain high for a period of time significantly longer than during the last rate cycle. The median deposit beta has reached only 25% so far in this cycle, whereas earning asset yield beta has hit 30%. Our optimistic scenario is that the betas from the previous cycle playout in this cycle. This, alone, would result in an estimated median decline in net interest margin of 33 basis points from 2Q23 levels.

Our base case is that bank net interest income is headed lower and that pressure on net interest margins will be worse than is currently expected and worse than it was the last rate cycle for at least the following reasons:

Low rates persisted over a long enough period of time that banks overestimated their core deposit base and deployed what they thought was permanent liquidity into low-yielding assets with extendable maturity in a higher rate environment.

Based on history, bank deposit rates are currently nowhere near where they need to be to compete with alternatives.

Rates rose so rapidly that banks didn’t have time to reposition their balance sheets for a higher rate environment and were locked into, in some cases, significant negative carry on what should have been liquid assets.

Low-yields from mortgage-backed securities, instead of being reset to higher rates, will bleed into earnings until rates subside enough to remove the earnings and capital implications from restructuring securities portfolios.

We are likely in a higher-for-longer rate environment, perhaps with a higher natural interest rate regime, which will grind bank funding costs higher over time.

Early optimism about banks’ ability to weather the higher rate environment has been mistakenly influenced by the early repricing of banks’ earning assets due to the increase in bank asset sensitivity over the past decade, and the runoff of excess liquidity, i.e., “surge” deposits, that has delayed the need to raise deposit rates to retain necessary funding.5

After suffering net interest margin compression, banks have a credit cycle to look forward to – but that’s another subject entirely.

For the 270 banks modelled by Cybiont Capital, the median expected change in net interest income for the next twelve months is a decline of 2.5%. Among banks where there is an active consensus, the median consensus forecast is for an increase of 4.6%.

Ironically, the Fed facility that was created after the failure of Silicon Valley Bank was created to assist banks in just such manner of obfuscation of banks’ real equity positions and facilitated a longer-term destruction of equity by providing the means to produce negative carry such as Zion’s. But since supervisory laxity tends only to cure by creating moral hazard, it wasn’t a surprising move.

Since there isn’t a universally accepted way to calculate a funding beta, statistics about betas aren’t always useful or comparable. One problem is that talking about “beta” over a prefixed time period, as many analysts do, isn’t terribly relevant if the rate cycle is likely to last significantly longer than that prefixed time period. We discuss here the extent of bank funding beta to date in this cycle; but that is only useful for comparison to where they were this far into the last rate cycle. What matters is what the final rate-cycle beta will be once rates begin to decline substantively.

Adjusting funding mix can buy time for banks to hold deposits rates steady; but it still raises funding cost since borrowings incur significantly higher cost than deposits for most banks. Moreover, there are limits to the amount of alternative funding that a bank can substitute before raising deposit rates because most of these alternative sources are secured by assets that are subject to collateral haircuts.

As bank investors we had to change our definition of “hot” money. In the past, we could simply look at a bank’s level of brokered deposits or fed funds borrowings to quantify “hot” money. But a flight to quality, pandemic spending patterns, paymentmoratoriums, and government transfers resulted in a “surge” of deposits at banks. Also, given the duration of the low-rate environment, banksaccumulated significant amounts of “warm money” masquerading as “core” deposits. These are“apathy” deposits that people let sit in banks because the cost/benefit of moving them wasn’t compelling until rates rose substantively.