LTCM: 25 Years On

The (real) reasons Long-Term Capital Management failed

Next month marks the 25th anniversary of the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management. In the four-and-a-half short years it was alive, the firm established a name for itself on Wall Street while remaining largely anonymous beyond. In death, it became well-known the world over.1

The rise and fall of LTCM has all the hallmarks of a great story: brilliant minds (including two Nobel laureates); dazzling success; enormous wealth; a sudden, perilous downfall; risk of devastating collateral damage; and a thrilling finale. The story burrowed its way into public consciousness as the finance industry’s Titanic. One book about it, When Genius Failed, became an international bestseller and is still required reading for anyone who works or invests in markets.

Even today, LTCM’s shadow endures. In a paper released last month discussing regulatory approaches to investment funds, the Central Bank of Ireland cites LTCM as a cautionary tale. Having sustained significant losses, “the failure of LTCM had the potential to generate broader contagion effects to the financial sector,” it reminds us. “Subsequently, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York brokered an injection of $3.6 billion from some of the largest creditors of LTCM… Without this, LTCM would not have been able to meet its payment obligations by the end of September 1998.”

The official anniversary of LTCM’s downfall is September 23. That was the day William McDonough, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, gathered top officials from sixteen of the world’s most powerful banks and investment houses into a room and told them to find a solution to the mess LTCM was in. LTCM was big – it had over 60,000 trades on its books comprising over $125 billion of assets and $1.4 trillion notional value of derivatives. McDonough was worried that a disorderly unwind of the firm’s positions would snowball through markets leading to catastrophic losses that would “pose unacceptable risks to the American economy.” Fourteen of the sixteen firms agreed to inject capital into LTCM to keep it afloat.2

But it was back in August that the downfall began. On August 21, 1998, Eric Rosenfeld, one of the partners of LTCM, was about to tee-off on a golf course in Sun Valley, Idaho, where he was vacationing with his family. Russia had defaulted on its debt earlier that week but the firm didn’t have much Russian exposure and so he wasn’t too concerned. At 9am, he called the office. “It was bedlam,” he recalls.

The firm’s core business was arbitrage, principally bond market arbitrage. Rosenfeld and his colleagues would buy undervalued bonds and sell short overvalued bonds affected by similar factors in order to capture price differentials without taking directional market risk. A textbook trade involved “on-the-run” and “off-the-run” bonds. LTCM would buy “off-the-run” bonds with 29 years left until maturity and sell “on-the-run” bonds – the most recently issued US Treasury bonds with a 30-year maturity. Because the freshly issued bonds tended to be more liquid, they would trade at a premium, reflected in a lower yield. LTCM could buy the 29-year bond at a yield of 5.62% and sell the 30-year bond at a yield of 5.50% – its objective being to pick up the 0.12% yield differential over time. Convergence would normally occur within six months, since by then the US Treasury would have issued another 30-year bond sucking the liquidity (and the premium) away from the one on LTCM’s books.

By pairing both legs of the trade, LTCM aimed to eliminate directional risk. A 30-year bond may normally trade in a range of 0.85 percentage points around its 5.50% yield. The combination of both trades reduced that variance by 25 times.

LTCM did lots of trades like this. It had as many as 10 distinct categories of trades on its books, across interest rate swaps, fixed rate residential mortgages, European and Japanese government bonds, stock market volatility, merger-and-acquisition activity, dual-listed companies and more. Diversification added to the pairing strategy to reduce risk. Before August, LTCM had lost no more than $125 million on a single day across an asset base that peaked at almost $140 billion.

But August 21, 1998 was different. One of LTCM’s strategies was risk arbitrage, where it would bet on the outcome of merger-and-acquisition deals by buying the stock of a merger target and selling short the stock of the acquirer. That morning, one of the deals on which it had a position was called into doubt. The target’s stock fell by 50% and LTCM was in the hole for $160 million. One by one, other trades started to fail, trades that should not have been correlated. A single bet tied to the US bond market lost $100 million; another $100 million evaporated in the UK. By the end of the day, LTCM was down $550 million – the single biggest daily loss in the firm’s history and five times more than anything its models anticipated.

Rosenfeld flew back home to consult with his colleagues. On Sunday August 23, they gathered at the firm’s headquarters in Greenwich, Connecticut to analyse what was happening. “One after another, LTCM’s partners, calling in from Tokyo and London, reported that their markets had dried up,” recorded the Wall Street Journal. “There were no buyers, no sellers. It was all but impossible to manoeuvre out of large trading bets. They had seen nothing like it.”

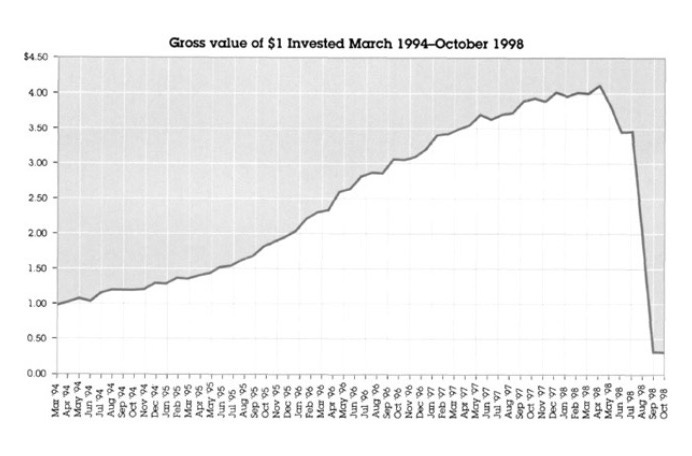

It didn’t let up. By the end of August, LTCM was down 44% for the month; year to date, the fund was down 52%.

John Meriwether, the firm’s founder, called an old market contact, Vinny Mattone, for advice. “You’re finished,” Mattone told him. “When you’re down by half, people figure you can go down all the way. They’re going to push the market against you. They’re not going to roll [refinance] your trades. You’re finished.”

Initially, Meriwether, Rosenfeld and the team thought they could soldier on. They faxed a letter to investors on September 2 blaming losses on a major increase in volatility and flight to liquidity caused by the crisis in Russia, magnified by seasonally thin markets. “Many of the Fund’s investment strategies involve providing liquidity to the market. Hence, our losses across strategies were correlated after-the-fact from a sharp increase in the liquidity premium,” they explained.

At the time, the team considered the market conditions temporary; they invited clients to contribute more capital to the fund, reminding them that many had asked to add to their investment over a period when the fund had been closed. “[W]e see great opportunities in a number of our best strategies, and these are being held by the Fund,” they wrote. “[T]he opportunity set in these trades at this time is believed to be among the best that LTCM has ever seen.”

But Mattone was right – the firm was finished. Having run through $1.8 billion of its $4.1 billion of capital in August, LTCM ran through $1.9 billion more in September.

What Went Wrong: Take One

Over the years, commentators have looked back at this episode to analyse what the team did wrong, how genius of this magnitude could fail.

“If you take the 16 of them, they have about as high an IQ as any 16 people working together in one business in the country, including Microsoft,” Warren Buffett told a group of students a few weeks after the collapse. “An incredible amount of intellect in one room. Now you combine that with the fact that those people had extensive experience in the field they were operating in. These were not a bunch of guys who had made their money selling men’s clothing and all of a sudden went into the securities business. They had in aggregate, the 16, had 300 or 400 years of experience doing exactly what they were doing and then you throw in the third factor that most of them had most of their very substantial net worth in the business. Hundreds and hundreds of millions of their own money up (at risk), super high intellect and working in a field that they knew. Essentially they went broke. That to me is absolutely fascinating.”

Various reasons have been given for the downfall. One is that the LTCM partners were overly beholden to their models. Rosenfeld was a finance PhD; he had spent several years as an assistant professor at Harvard before joining up with Meriwether and, like many of his fellow partners, was fluent in mathematical modelling.

“LTCM’s experts start with an academic research framework and quantitative orientation to build and refine models and to put concepts into practice on a large scale,” the firm’s marketing materials note. Its brochure describes LTCM not as a fund but as a “financial technology company.” (A red flag if ever there was one.)3

But many of the pricing anomalies that LTCM sought to exploit could be identified without sophisticated modelling at all. Although models were important to how trades were implemented and risks assessed, partners knew that their models were approximations to reality: They were far too experienced to enter into positions without an understanding of why a trading opportunity had opened up. The firm’s overall risk model even incorporated judgement-based buffers. Thus, investors were told to expect annual volatility of 20%, higher than both the volatility the risk model anticipated (14.5%) and the volatility the fund historically realised (11%).4

Another reason presented for the firm’s demise is that it employed too much leverage. “At LTCM the best minds were destroyed by the oldest and most famously addictive drug in finance,” wrote Carol Loomis for Fortune magazine. “Had the fund not grievously overextended itself, it might still be trucking along, doing its thing, working those brain cells.” Indeed, curtailing excessive leverage in the finance industry became a key policy conclusion in the aftermath of the collapse (albeit not one that was implemented in time for the 2008 financial crisis).

LTCM did leverage up, with unfortunate timing, going into 1998, when it returned $2.7 billion of capital to investors without reducing its asset base commensurately. But prior to that, its leverage had been managed tightly. Before the capital distribution, the firm had an equity base of $7.5 billion and a balance sheet of $129 billion, equivalent to a 17x leverage ratio. Yet 80% of its positions were in government bonds of G-7 countries, traditionally lower risk assets (and reflected as much in bank risk weighting methodologies). And compared with banks, LTCM ran a conservative balance sheet. At the end of 1996, Morgan Stanley, whose equity base was similarly sized at $7.4 billion, ran a 27x leverage ratio; Salomon Inc ran a leverage ratio as high as 42x.5

As Donald MacKenzie, a professor of sociology, notes, “Blaming LTCM’s crisis on leverage is rather like attributing a plane crash to the fact that the aircraft was no longer safely in contact with the ground: it identifies a necessary, but in no sense a sufficient, cause. Leverage at best explains the fund’s vulnerability to the events of August and September 1998, but does not itself explain those events.”

So if it was neither seduction of models nor leverage that caused LTCM to implode, what was it? Join me over the paywall to explore…

What Went Wrong: Take Two

To understand, it helps to model LTCM not as a hedge fund but as a bank (although it’s also true that the best model for a bank is often a hedge fund). Roger Lowenstein, author of When Genius Failed, acknowledges as much in the subtitle of his book: “The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management: How One Small Bank Created a Trillion-Dollar Hole.”

The model reflects LTCM’s heritage. John Meriwether ran the arbitrage desk at Salomon Brothers becoming vice chair of the whole firm, in charge of its worldwide Fixed Income Trading, Fixed Income Arbitrage and Foreign Exchange businesses. In the years 1990 to 1992, proprietary trading accounted for more than 100% of the firm’s total pre-tax profit, generating an average $1 billion a year. LTCM was in some ways a spin-off of this business.

Indeed, LTCM partners viewed their main competitors as the trading desks of large Wall Street firms rather than traditional hedge funds. Thus, although they structured their firm as a hedge fund (2% management fee, 25% performance fee, high watermark etc) they did everything they could to replicate the structure of a bank. So investors were required to lock-up capital initially for three years to replicate the permanent equity financing of a bank (hence “Long-Term Capital Management”). They obtained $230 million of unsecured term loans and negotiated a $700 million unsecured revolving line of credit from a syndicate of banks. They chose to finance positions over 6-12 months rather than roll financing daily, even at the cost of less favourable rates. And they insisted that banks collateralise their obligations to the fund via a “two way mark-to-market”: As market prices moved in favour of LTCM, collateral such as government bonds would flow from their counterparty to them.

If there was one risk LTCM partners were cognisant of it is that they might suffer a liquidity crisis and not be able to fund their trades. It was a risk they took every effort to mitigate.

But in modelling themselves as a bank, they forgot one key attribute: diversification.

“We set up Long-Term to look exactly like Salomon,” explains Eric Rosenfeld. “Same size, same scope, same types of trades… But what we missed was that there’s a big difference between the two: Long-Term is a monoline hedge fund and Salomon is a lot of different businesses – they got internal diversification from their other business lines during this crisis so therefore they could afford to have taken on more risk. We should have run this at a lower risk.”

It’s a risk monolines in financial services often miss. And LTCM wasn’t the only monoline to fall victim to market conditions in 1998. In the two years that followed, eight of the top 10 subprime monolines in the US declared bankruptcy, ceased operations or sold out to stronger firms. The experience prompted some financial institutions – such as Capital One – to embrace a more diversified model.

When the global financial crisis hit in 2007, monoline firms went down first. And in the recent banking crisis of 2023, those banks that failed were characterised by lower degrees of diversification.

There’s another factor that also explains the downfall of LTCM, one that similarly has echoes in the banking sector. At the end of August, LTCM was bruised but it was far from bankrupt. It had working capital of around $4 billion including a largely unused credit facility of $900 million, of which only $2.1 billion was being used for financing positions.

But the fax Meriwether sent clients on September 2 triggered a run on the bank. “We had 100 investors at the time, and a couple of fax machines,” recalls Rosenfeld. “By the time we got to investor 50, I noticed that the top story on Bloomberg was us… All eyes were on us. We were like this big ship in a small harbour trying to turn; everyone was trying to get out of the way of us.”

While the August losses reflected a flight to quality as investors flocked to safe assets, the September losses reflected a flight away from LTCM. The price of a natural catastrophe bond the firm held, for example, fell by 20% on September 2, even though there had been no increase in the risk of natural disaster and the bond was due to mature six weeks later. As the firm was forced to divulge more information to counterparties over the course of September, the situation worsened. “The few things we had on that the market didn’t know about came back quickly,” Meriwether later told the New York Times. “It was the trades that the market knew we had on that caused us trouble.”

In addition, illiquid markets gave counterparties leeway in how to mark positions, and they used the opportunity to mark against LTCM to the widest extent possible so that they would be able to claim collateral to mitigate against a possible default (the flipside of the “two way mark-to-market”). The official inquiry into the failure noted that by mid-September, “LTCM’s repo and OTC [over-the-counter] derivatives counterparties were seeking as much collateral as possible through the daily margining process, in many cases by seeking to apply possible liquidation values to mark-to-market valuations.” And because different legs of convergence trades were held with different counterparties, there was very little netting. In index options, such collateral outflows led to around $1 billion of losses in September.

Nicholas Dunbar, who wrote the other bestselling book about LTCM, Inventing Money, quotes a trader at one of LTCM’s counterparties (emphasis added):

“When it became apparent they [LTCM] were having difficulties, we thought that if they are going to default, we’re going to be short a hell of a lot of volatility. So we’d rather be short at 40 [at an implied volatility of 40% per annum] than 30, right? So it was clearly in our interest to mark at as high a volatility as possible. That’s why everybody pushed the volatility against them, which contributed to their demise in the end.”

The episode is a lesson in endogenous risk. It’s a risk that differentiates securities markets from other domains governed by probability. “The hurricane is not more or less likely to hit because more hurricane insurance has been written,” mused one of LTCM’s partners afterwards. “In the financial markets this is not true. The more people write financial insurance, the more likely it is that a disaster will happen, because the people who know you have sold the insurance can make it happen. So you have to monitor what other people are doing.”6

Epilogue

After the consortium acquired a 90% equity stake in LTCM’s portfolio together with operational control, the environment calmed. The portfolio took 15 months to liquidate and the participating banks ended up making a 10% return on their investment (as well as avoiding any losses that would have been incurred had they not stepped up).

Most outside investors didn’t do too badly either. According to Rosenfeld, the median investor earned a 19% rate of return from inception – largely for having been cashed out of their profits at the end of 1997. And of 100 investors in the fund, only 12 lost money, with just six of them losing more than $2 million (the largest being UBS which did a special deal with LTCM in 1997 to gain exposure and ended up having to write off $680 million).

For Warren Buffett, it was the deal that got away. In the discussions to save LTCM, he tabled an offer in partnership with AIG and Goldman Sachs to buy out LTCM for $250 million plus a further $4 billion capital injection. But the one-page offer document raised technical questions and was timed to expire after two hours. Buffett, who was travelling at the time, could not be reached for clarification. “If I’d been in New York, we’d have made the deal,” he said later. Rosenfeld reckons Buffett would have doubled his money.

As for the partners, they splintered to form two new funds. Rosenfeld went with Meriwether to set up JWM Partners; some of the others established Oak Hill Platinum Partners (later renamed Platinum Grove). Both funds employed similar strategies to LTCM – with less leverage – growing to $10 billion of assets under management between them. In 2008, they were no longer the headline act, but they suffered nonetheless – down 40%. Vinny Mattone’s advice ringing in his ears, Meriwether decided to wind up his fund before the market forced it.

Twenty five years on, the story of LTCM still resonates. At one level an Icarus tale of hubris, it is more usefully a case study in how markets work. Finance is rich with such stories, but LTCM lives on.

Lots of useful resources via the links, and if you liked this piece, please ♡.

I must confess, as an analyst on Wall Street at the time I was not familiar with LTCM, but then the firm wasn’t interested in the directional equity trades I trafficked in. Like everyone around me I quickly got up to speed during September 1998.

Crédit Agricole and Bear Stearns chose not to participate in the consortium. Bear Stearns’ opt-out in particular ruffled feathers because it was a clearing broker for LTCM. “It was as if Bear were breaking a silent code,” Roger Lowenstein wrote in 2000 in When Genius Failed. “It would pay a price in the future, Allison [architect of the plan] vowed.”

When the markets wobbled in August 1998, several insiders described it as a “ten standard deviation event” – something that should happen once every 3.3 x 10^20 years (longer than the life of the universe). Nassim Taleb points out that if an outcome so remote in probability actually happens, the likelihood is that the models you have been using to measure it may well be flawed. He calls it Wittgenstein’s Ruler. “Are you using the ruler to measure the table or the table to measure the ruler?” he asks.

As it turned out, even the buffers understated the rise in both volatility and correlation. Historically, the level of correlation between the different components of LTCM’s portfolio had been 0.1 or less. LTCM performed its risk analysis at around what it took to be a conservative level of 0.3. When the crisis hit, correlations jumped to 0.7.

LTCM’s rationale for returning capital to investors was as follows: “From inception, the Fund has implemented its investment strategies subject to a constraint on its level of risk and subject to the requirement of maintaining adequate liquidity capital. The Management Company believes that these two constraints are not binding currently and the Fund has excess capital. This has occurred, primarily, because of a substantial increase in the capital base from the larger-than-expected, past realized rates of return, and high reinvestment rates elected by the Fund’s investors. Therefore, it has become necessary to reduce the amount of capital significantly to bring the Fund’s capital base more in line with its risk and liquidity needs.”

LTCM had a foretaste of the impact of crowded trades in July 1998. The previous year, Salomon had been taken over by Travelers Corporation and its CEO, Sandy Weill, wanted to reduce risk. The firm’s arbitrage desk had not been as profitable since Meriwether and his team had left to set up LTCM; in the first half of 1998 it was down $200 million and Weill decided to close it in a decision announced on July 7. The forced selling put pressure on LTCM’s similar trades and it incurred substantial losses, reversing profits it had made at the beginning of the month.