Last week’s post had over half a million views and brought with it many new subscribers. If this is your first time receiving Net Interest, welcome. Each week, I distil 25+ years of experience analysing and investing in the finance sector into a newsletter delivered straight to your inbox.

Banks aren’t like other companies. A retailer or a builder goes bust and it leaves a hole in the market for others to step into, an opportunity for them to pick up market share. But when a bank goes bust, it sends ripples across the industry, impacting them all. Few executives of US regional banks this week welcomed the opportunity to win over Silicon Valley’s orphaned customers; they were too busy convincing their own customers they were different.

There are several typical channels for financial contagion.

One is that banks own similar assets to each other. When a bank is forced to liquidate its assets, their prices may take a hit. Other banks holding the same assets will have to mark their holdings down accordingly. To the extent banks use these assets as collateral against borrowings, their access to such borrowing may be curtailed. In a worst case scenario, banks may have to sell assets to raise liquidity instead, and a vicious spiral ensues. This was part of the story of the last financial crisis.

Another is that banks originate similar assets to each other. Just like other companies, banks are a competitive breed. Many will sacrifice underwriting discipline in order to retain their market position. “As long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance,” the CEO of one bank famously remarked sixteen months before seeking a government bailout. This behaviour is one of the reasons policymakers are not as keen on competition in the banking industry as they are in other industries. In a stand-off between financial stability and competition, authorities will always choose financial stability. Again, this was part of the story of the last crisis.1

This week’s fears of contagion have little to do with these factors. Silicon Valley Bank’s assets were largely money-good. It sold a $21.4 billion portfolio of securities to Goldman Sachs days before its collapse but in the markets where they trade, that wasn’t enough to move the price. Indeed, Goldman may even have made a $100 million profit on the trade.

Its loans were also pretty good. Non-performing loans made up just a fraction of its loan book and they were covered more than four times over by provisions. Most of its loans reprice over the short term so weren’t underwater from higher interest rates in the same way the securities book was. Ironically, if Silicon Valley Bank had written bad loans, it would have been given more time to work them out. In the last crisis, bank failures peaked in 2010, a full year after bank stock prices bottomed.

Rather, contagion is spreading through an altogether different channel: customer confidence. The speed with which Silicon Valley Bank collapsed has customers questioning the fragility of the very model banks operate under. One day, Silicon Valley was open for business; the next it wasn’t. On Tuesday the CEO was at a conference calmly talking about his hobbies, on Wednesday the bank’s stock was still trading at a premium to book value, on Thursday it lost a quarter of its customer deposits, and on Friday it was gone.

So quick was the collapse, the authorities didn’t even wait until 5pm to close down the bank. When Washington Mutual was shut in 2008, it had lost $17 billion of deposits over two weeks; Silicon Valley Bank lost $42 billion in a single day. Washington Mutual’s stock had been under pressure for some time (I was short at the end of 2006); Silicon Valley Bank was trading above its Covid low until its very last day.

Signature Bank suffered the same fate. Two days after Silicon Valley Bank was shut, authorities in New York closed down Signature Bank. Former US Congressman Barney Frank, one of the architects of the post financial crisis regulatory regime, was a board member. He didn’t see it coming. “Apparently, the Department of Financial Services in New York, which did the closing, hasn’t said we were insolvent,” he said. “I wonder, are we the first bank to be closed, totally, without being insolvent?”

Nor did any of the signals designed to project confidence work. Moody’s conferred an A1 credit rating on Silicon Valley Bank right up until the moment it collapsed. The bank’s tier 1 risk-based capital ratio – a measure of its capital adequacy – was a sturdy 15.4%, close to twice its required regulatory minimum. And supervisory oversight was assured. As a “Category 4” banking organisation, Silicon Valley did not have to disclose its liquidity coverage and net stable funding ratios like larger banks, but these were metrics regulators should have been monitoring.2

In the event, none of the pre-emptive protections worked. “If those banks can be closed down so suddenly, why can’t mine?” customers might rightly ask.

We discussed the specific reasons why Silicon Valley Bank failed last week. We highlighted the asset side of its balance sheet, which was chock-full of long duration securities, most of which had been pushed underwater by rising rates yet did not have to be marked as such. And we highlighted its deposit base, which was heavily concentrated around a relatively small number of uninsured depositors, whose average deposit balance was $4.2 million (versus the $250,000 insurance threshold).

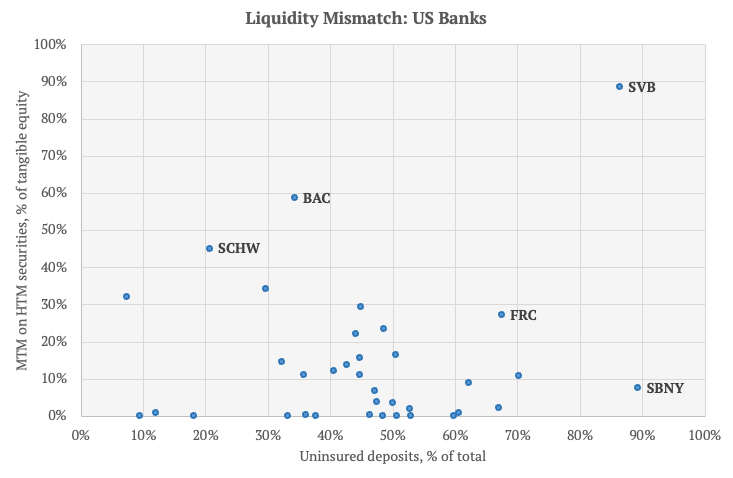

In the past week, people have debated which of the two factors is the more important. Some argue it was the losses in the securities book and draw concern from a recognition that US banks are sitting on $620 billion in aggregate mark-to-market losses as at the end of 2022. Others focus more on the deposit side, arguing the flighty nature of Silicon Valley’s deposits would have caused the bank problems whatever assets it held. The reality is that it was the combination of both factors that led to Silicon Valley’s demise. Its deposit base might have been fine if matched with short-dated securities, and it might have been able to withstand the mark-to-market losses with a more resilient deposit base.3

Nevertheless, depending on which factor you put more weight on, you can find your channel of contagion. The chart shows the banks on the frontline.

One thing we learned from the last crisis is that the market leads regulators. Before the Federal Reserve started conducting stress tests on US banks, analysts and investors performed their own. We would calculate the “burndown” tangible book value of banks by estimating cumulative losses across their various loan categories and writing down the overall book accordingly. Any gap between “burndown” tangible book value and some level of sustainable capital would have to be filled via a common equity raise.

Some bank executives argued that preferred capital would do the job, as per regulatory guidelines, but the market pushed back. No surprise the market view prevailed. “As you know…based on our Tier 1 of 11.9% [which includes preferred capital], we have been very well-capitalised,” Citigroup’s CEO announced to the market in February 2009. “However, the markets became increasingly focused on tangible common equity, and the stock price and preferred prices reflected this focus.” Citigroup went on to launch a dilutive exchange of preferred to common stock.

The parallel today is that the market will not wait for regulators. For sure, regulation will change. It is in the nature of regulation that it addresses the last crisis, and it is the nature of risk that it emerges where no-one is looking (policymakers had long anticipated that the next crisis would emerge from the non-banking financial sector, rather than the banking sector). Smaller banks will likely come under the same scrutiny as larger banks. Like the large banks, they may be obligated to sweep mark-to-market gains and losses in their available-for-sale securities portfolios into regulatory capital, and may have to disclose liquidity ratios.

But the market won’t wait, and in the meantime deposits are on the move. Just as new indicators of stress became useful during the global financial crisis, several will come to dominate now. Those I will be looking at include the Federal Reserve H.8 report, released every Friday at 4.15pm. It collates deposit volumes across all US banks and will highlight any migration from small banks to large banks.

Bank deposit rates are also worth watching. No doubt they will go up across the board as deposit rates catch up with the interest rate hikes we’ve seen over the past year, but banks towards the top of the leaderboard may be signalling a particularly hard time retaining deposits.

Finally, activity at the Federal Home Loan Banks is worth watching as banks’ “lender of next-to-last-resort”. We talked about Federal Home Loan Banks two weeks ago in the context of Silvergate, which received a lifeline from them for a couple of months until its end. They issue bonds every day which they turn around to fund advances to banks; Monday’s issuance was a record high.

We won’t know for a couple of weeks yet whether current events turn into a crisis or not. But at the very least, depositors are now much more aware of the risk/return involved in making bank deposits and will assess relationships accordingly. Along the way, they are realising that a bank is not a business, it’s a balance sheet.

Paid subscribers can read on for further analysis on several institutions at the “frontline of contagion” — Credit Suisse, Charles Schwab and First Republic Bank.