Community First

America loves its small banks. But in an age of technological change, can they survive?

There are a lot of banks in America, like, a lot. So many that there aren’t even enough names to go round. Tell someone you bank with ‘First Federal Bank’ and you’ll need to clarify if you mean the one in Florida, or North Carolina, or Tennessee, or one of the 17 First Federal Savings and Loan Associations scattered across the country. The sparsely populated state of North Dakota alone has more banks than Canada, its neighbor to the north – a country with 50x the population. Banks are so numerous that below a certain threshold, they can fail without so much as a whimper. Just this year, regulators shut down two banks without making headlines: The Santa Anna National Bank in Texas, with $64 million in assets, and Pulaski Savings Bank in Chicago, with $50 million in assets.

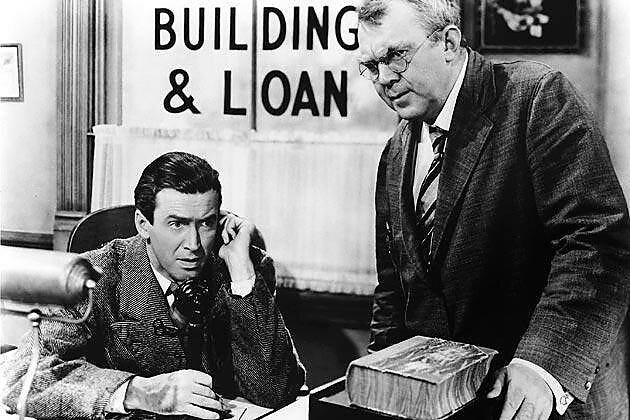

As a non-American, I often wonder if this makes sense. In my country, we have 117 banks – that’s one for every 600,000 people, compared with one for every 80,000 in the United States.1 Other utilities like rail and telecommunications have attained similar levels of consolidation. More curious, though, is how deeply this fragmented banking structure is woven into American identity. Perhaps it’s the civic ideal immortalized in classics like It’s a Wonderful Life, but America’s long tail of small banks holds a special place in the national culture.

This week, the Federal Reserve hosted a conference in Washington to celebrate them. In attendance were financial celebrities including Jim Cramer of CNBC Mad Money, Blackstone CEO Stephen Schwarzman and Robinhood founder Vlad Tenev. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent was also there.2

“I remember listening to Farm Radio right after the Silicon Valley [Bank] debacle,” he told the audience (apparently he is the first Treasury Secretary since the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who is also a farmer). “And I was just struck by what the presenter was saying… The big banks they’re going to come in, they’re going to buy up our banks; they don’t play baseball with your son, they don’t play softball with your daughter, they don’t go to your place of worship, they don’t know you from the Rotary Club — what are we going to do?”

Bessent affirmed the administration’s commitment to protecting smaller banks. “We want to get back to leveling the playing field,” he said. Others were equally effusive. “The backbone of America,” Jim Cramer described them. “It’s good to have local banks,” said Schwarzman. Indeed, so culturally resonant is the ideal of community banks that even Jamie Dimon, CEO of America’s largest bank JPMorgan, pays homage. “Regional and community banks have exceptional local knowledge and presence and are critical in serving thousands of towns and certain geographies,” he writes in his shareholder letter.

Where does this extraordinary political and cultural sway come from, and can it persist? In a world where technology and scale increasingly determine competitive advantage, how long can America’s distinctive banking structure survive?