Sometime around spring 2010, I was sitting in a coffee shop in New York passing time with one of the best equity fund managers of his generation. We were both over from London visiting American companies and he’d had a revelation. Having built his career investing in European – predominantly UK – stocks, he decided he needed to pivot to the US if he was to replicate the strong performance he’d shown so far. He pulled out a napkin and scribbled down a model portfolio: JPMorgan, Nike, Coca Cola, Colgate-Palmolive, IBM.

“Mega-cap growth stocks,” he said. “That’s the investment theme for the next ten years. The winners will be companies with strong balance sheets that benefit from global demand trends.”

Back in London, he put the portfolio on, later swapping out IBM for Amazon and Google. Two years later he changed the name of his fund to better reflect its new emphasis.

At the time, the US made up around 40% of global stock market capitalization. Its economy had just come out of recession and although a recovery was underway, it wasn’t yet showing signs of exceptionalism. That was about to change. Over the next 15 years, the US market went on to grab over 60% of global stock market capitalization. A $10,000 investment in US stocks made in 2010 is worth $73,000 today; the same in Europe is worth only $25,000. And rather than fading, the gap has only widened. Last year, Europe underperformed the US by the greatest amount since 1975 in US dollar terms.

I don’t often post a chart so early, but this is a good one:

There are several related explanations for the divergence. Europe doesn’t have an equivalent of Amazon or Google or any of the other “Magnificent-7” which now make up over a third of the S&P 500 index. More broadly, the global demand for US companies’ products has led them to outgrow their domestic economy. Equity market capitalization now stands at 194% of GDP in the US, having risen steadily over the past decade and a half, while remaining broadly flat elsewhere at around 60%. US company earnings have simply outpaced those of the rest of the world.

For European asset managers, this has been a frustrating period. All the more so because the growth of indexation – a big feature of the industry in the US – hasn’t taken hold in Europe to the same extent. While passively-managed funds now control more assets in the US than their actively-managed competitors, in Europe the market share of passive funds is still only 30%. Cumulatively, European fund managers have taken in more active money than passive money since 2007 – to the envy of peers in America, where around $8 trillion has been reallocated.

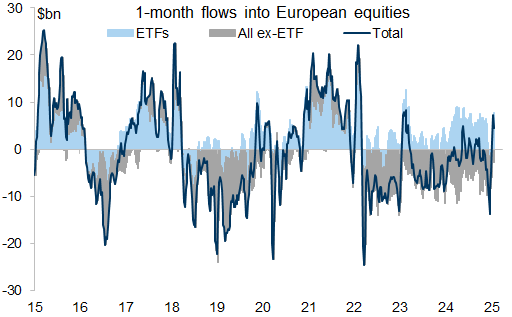

Yet weak markets have meant they haven’t been able to capture any benefit. Assets managed out of Europe make up 21% of global assets under management, down from 29% in 2010, according to Boston Consulting Group. Firms have experienced three years of fairly consistent outflows through to the end of 2024.

Recently, though, enthusiasm for Europe has been rekindled. In the first few weeks of the year, the STOXX 50 index of European blue chips has enjoyed a bounce, up 7% so far. Bank of America’s much followed survey of global fund managers reveals a swing in sentiment back towards the region. In January, respondents’ European weightings rose by the most in any month since 2015, and by the second most ever.

Meanwhile, European asset managers have begun a process of consolidation. This week, Italian firm Generali Investments agreed to tie up with Paris-based Natixis Investment Managers to create the second largest asset management firm in Europe, with €1.9 trillion of assets. It follows an announced deal between BNP Paribas and AXA Investment Managers (combined assets under management of €1.5 trillion) as well as one between Banco BPM of Italy and asset manager Anima (€220 billion).

With 61% of its combined assets under management in Europe, the Generali-Natixis combination will be hoping these seeds of enthusiasm flower into something larger. To explore the bull case for Europe and what it means for its asset management industry, read on…

Incidentally, if you’re not yet a paid subscriber, now’s your chance. Next week I am launching Net Interest Extra as an interview series exclusively for paid subscribers. I come across a lot of interesting people via Net Interest, many of them experts in their field. Net Interest Extra is my platform for channeling that expertise back to readers. As well as access behind the paywall and an invitation to a fully searchable archive of over 200 issues, paid subscribers will now also be able to enjoy interviews with authors, investors and finance professionals. To upgrade, click the link.

Valuation isn’t a sufficient condition for stock market outperformance, but it helps. Last year’s meager return in European shares relative to what the US offered leaves them trading at a record 40% forward P/E valuation discount. While the US trades well above its 20 year median multiple, at around 21.7 times, Europe remains glued to its historic average of 13.2 times. Some of the difference is Big Tech, but that only covers a fraction of the difference. Adjusting for large technology companies, the US multiple settles at 19.1 times.

Positioning is also at an extreme. Despite the uptick in sentiment reflected in the Bank of America survey, most investors remain underweight Europe. Investors have been paid to be overweight US relative to Europe for most of the past 15 years with little incentive for them to change their mind. Attendees at Goldman Sachs’ annual strategy conference in London this week voted Europe as their least preferred region.

One trend that could bring the valuation gap into focus is a convergence of economic prospects. The International Monetary Fund forecasts economic growth of 2.2% in the US and 1.6% in Europe this year. While the US continues to grow more quickly, it is no longer expanding at twice the rate of Europe. Nor is growth uniform within Europe. Although the larger economies lag, peripheral economies are doing well. Spain and Ireland each grew more quickly than the US in the third quarter of last year and Poland was on par. I’ve been meaning to write up Greek banks here for a while – a glance at what is happening there illustrates the recovery that has revitalized that country.

In addition, interest rates are also expected to drop by more in Europe than the US. Economists are expecting 100 basis points of cuts in Europe, against just 25 basis points in the US. The region may see fiscal expansion, too. Government debt as a share of GDP has grown by 25% in the US since 2011; in Europe, it is broadly unchanged. Although the structural case for US outperformance is plain, cyclical factors like fiscal deficits, falling savings rates and an energy cost gain have played a role that may no longer be sustainable to the same extent.

In spite of his rhetoric, President Trump may also be a boon for Europe. An end to the war in Ukraine would be positive for gas prices and his lifting of a freeze on liquefied natural gas (LNG) export permits could be beneficial to European consumers. His business-friendly ethos may also inspire a response in Europe. At Davos this week, Richard Gnodde, vice chairman of Goldman Sachs’ international operations, talked about an increasing sense of frustration in Europe, where executives envy the corporate optimism on display in the US. “I wouldn’t be surprised if we see that community broadly becoming much more assertive,” he said.

Signs are beginning to emerge that the UK government is already responding. This week, the Treasury intervened in a Supreme Court case that had threatened to upend the motor financing market and the Chancellor of the Exchequer called on regulators to tear down barriers that hold back growth. We highlighted the Draghi report on European competitiveness here a few months ago; endorsements of its recommendations can only grow.

Of course, European stasis presents a difficult challenge and the lack of both a platform to foster technological development and deep capital markets to fund it are real structural impediments. But given valuation and positioning, it may not take much for markets to react. Firms like Natixis and Generali Investments, alongside other large European asset managers like Amundi and DWS, are getting ready.

Europe has traditionally been a more fragmented asset management market than the US. National differences in tax treatment, product preference and distribution strategy have kept markets distinct. According to the European Fund and Asset Management Association, there are 4,620 asset management companies active in Europe, up from around 4,500 in 2018.

Although the sector has witnessed a steady stream of M&A over the past 15 years, the urgency to consolidate has been lacking. One reason is the lower penetration of passive products, which have posed a key challenge to traditional asset management– a theme we discussed in BlackRock’s Barbell a few weeks ago (and in Trillions: The Rise of Passive before).

Europe’s lower passive share stems from its predominantly captive distribution model, in which funds are sold through banking networks. It’s difficult for a banking intermediary to command a distribution fee on a passive product, so there is little incentive to promote it. The outlier is the UK where open architecture is prevalent and passive penetration is correspondingly higher. In some countries, it’s difficult for similar models to gain a foothold. In France, tax incentives favor savings held in an insurance wrapper, which captive networks are better equipped to distribute. In Spain, mutual fund investors can defer capital gains when switching between funds, making them a superior choice to ETFs.

That’s not to say passive doesn’t have a role in Europe – it’s just that the shift is around ten years behind the US. A few years ago, SocGen migrated from a captive distribution agreement with Amundi to a partial open architecture model in which six managers, including passive-oriented BlackRock, got access to its retail distribution network. In Italy, Unicredit is already in breach of commitments under its exclusive distribution agreement with Amundi as it internalises a higher share of fund flows; the agreement is scheduled to roll-off in 2027.

Amundi may not mind. Following its acquisition of Lyxor in 2022, it became the second largest ETF player in Europe (behind BlackRock). DWS is third, via Xtrackers. Both have seen fee margins compress, yet they retain a strong position in a market where the top five players command an 80% share.

That’s in contrast to the active market, where the top ten managers have around a 30% share in long-only European Union domiciled equities. As passive catches up, the impetus to consolidate grows. Only a handful of European managers feature among the top 20 firms globally – Amundi and Generali-Natixis being two of them. This gives them fewer assets over which to spread costs.

“I know perfectly well that Natixis as a standalone entity can’t be a global champion in the long term,” Nicolas Namias, CEO of Natixis’ parent company, said this week. “But that’s the case for almost all the actors of asset management. That’s why there’s a movement of consolidation.”

Generali-Natixis may be the latest, but it won’t be the last. In December, Allianz and Amundi paused talks to combine their asset management businesses into a €2.8 trillion giant. A pick-up in underlying business activity could galvanize firms into action.

For investors looking on, Europe vs the US is a big call. My coffee partner in New York ran a US-oriented portfolio for the ten years he projected. More recently, he has pivoted again: to Europe. It’s no more a geographic call than it was back then. It’s simply, “we are overweight Europe because we find more ideas that are attractive there.” The US is exceptional, but in markets, trends rarely are.

Announcement: As I mentioned above, next week sees the launch of Net Interest Extra – my interview series exclusively for paid subscribers. In the first episode, I interview Duncan Mavin, author of the superb book, Meltdown, about the collapse of Credit Suisse. Paid subscribers will be notified when the episode lands. If you have friends or colleagues who would be interested in the expanded offering of a paid subscription, refer them via the link.

Great points raised in this post. Though at present it seems UK and Europe is not all that cheap once adjusting for growth relative to the US:

https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/ftcms%3A58d7265d-d30b-463b-9d86-774185804fd5?source=next-article&fit=scale-down&quality=highest&width=700&dpr=1

Ultimately, and as you rightly point, it's all about growth prospects. The how and when is key.

Very interesting and thought provoking indeed.

While you're at it, care to share perhaps what your friend (one of the greatest portfolio managers of our generation) thinks about US vs Europe now? Perhaps he's updated his view following his terrific run?