Banks in Disguise

Unmasking the Banks Inside Starbucks, Carnival, Naked Wines, Delta, Travel + Leisure

Net Interest is four years old this week! Thanks to all those who have supported the growth over that time. More than 80,000 people now receive the newsletter in their inboxes each week, including some of the most senior executives and smartest investors in the finance industry. For paying subscribers, the archive of 180+ issues provides evergreen insight on all aspects of the financial marketplace: fintech, housing, securities markets, emerging asset classes, investing, payments, banking basics, and more. I’ve received so much generous feedback, it’s made me very proud.

But looking back at my “manifesto” of May 2020, there’s one topic I haven’t delivered so much on. I said then that a newsletter dedicated to the study of financial institutions should be of interest to anyone fascinated by business because, “even companies that on the face of it aren’t, can be financial companies in disguise.” I used the example of Enron. In May 2001, Richard Grubman, co-founder of Highfields Capital, popped up on an earnings call hosted by Enron CEO, Jeff Skilling:

Grubman: You’re the only financial institution that cannot produce a balance sheet or cash-flow statement with their earnings.

Skilling: Well, you’re – you – well, uh, thank you very much. We appreciate it.

Grubman: Appreciate it?

Skilling: Asshole.The asshole comment made the exchange famous. Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind wrote in their book, The Smartest Guys in the Room, “[Ken] Rice, who was half asleep, bolted awake. Jaws dropped around the table.”

What’s not clear is whether jaws dropped over the asshole comment or the exposé that Enron was a financial institution. Aside from Richard Grubman, few outsiders understood it as one. Most analysts on the call were energy specialists. A few months later one of them, working for Goldman Sachs, would write, “We view Enron as one of the best companies in the economy, let alone among the companies in our energy convergence space.”

Unzip companies across a range of industries, I argued, and you will find financial companies lurking inside. This week we reprise the theme and spotlight five “banks in disguise”...

Starbucks

One of the best known non-bank banks is Starbucks – “a bank dressed up as a coffee shop”. Trung Phan, author of the excellent newsletter

, rates the misperception up there alongside “McDonald’s is a real estate company dressed up as a hamburger chain” and “Harvard is a hedge fund dressed up as an institution of higher learning”.Starbucks got into banking in 2008 when the man that developed its brand, Howard Schultz, returned for his second (of three) stints as CEO. The company had offered a gift card since 2001 but Schultz revitalized it, pairing it with a new loyalty program, Starbucks Rewards, which he launched in April 2008. By paying with a reloadable card, consumers could access perks such as free wifi and refillable coffee.

In 2010, Schultz put the card on an app, expanding its reach. Accepted at over 9,000 locations, it quickly became America’s largest combined mobile payments and loyalty program. Within a year, 25% of Starbucks transactions were completed on it. Today, more than 60% of the company’s peak morning business in the US comes from Starbucks Rewards members who overwhelmingly order via the app. The program has 33 million users, equivalent to around one in ten American adults.

According to Phan, these users load or reload around $10 billion of value onto their cards each year. Turning the coffee shop into a bank is that not all of it gets spent at once. As at the end of March, $1.9 billion of stored card value sat on the company’s balance sheet waiting to be spent – kind of like customer deposits. To give that some context, 85% of US banks have less than $1 billion in assets. And those deposits have enjoyed tremendous growth:

Now, this money isn’t real deposits. The Starbucks card invites you to treat it like cash, but it also says that value stored on it “cannot be redeemed for cash unless required by law.” The only way to cash out of Starbucks balances is to buy coffee.

But this actually gives the company some advantages. Wallet providers like PayPal, who promise real dollars on redemption, are required by law to maintain adequate reserves, which means they have to keep customer funds in low yielding segregated accounts or government bonds (although even government bonds can lead to crisis). All Starbucks needs to do to meet its promise is to keep its espresso machines turned on. Meanwhile, it can use customer funds to finance its operations.

In addition, the balances don’t pay interest. When interest rates were zero, that advantage was slight, but now the company has to pay 5.0% for 2034 debt, it becomes material. In fact, the advantage is even greater because not only does Starbucks not pay interest on customer funds, it regularly sweeps them into its own bank account when it concludes customers may have forgotten about them. And this is surprisingly common (or perhaps not so surprising when you think about how much unused credit you have sitting on forgotten gift cards). The company calls this breakage and it recognizes it as profit based on historic redemption patterns. In the fiscal year ending September 2023, it recognized $215 million of breakage, equivalent to 13% of stored balances. European banks were used to receiving interest on some customer deposits during the period of negative interest rates, but nothing like the -13% that Starbucks pays today.

That rate has actually increased over the years, from 11% when the company switched to its present accounting policy in 2019. There is some evidence Starbucks seeks to optimize it. Late last year, the Washington Consumer Protection Coalition (WCPC) accused the company of making it impossible for consumers to spend down their stored value cards by only allowing funds to be added in $5 increments and requiring a $10 minimum spend.

A big secret in banking is that customer funds get abandoned there too; the difference is that banks don’t get to keep hold of it. In the US, the process even has a name: escheatment. When accounts are left dormant for between three and five years, assets are transferred to the appropriate State Comptroller’s Office. New York currently manages $19 billion of unclaimed funds (if you think some of it is yours, you can file a claim here). The UK government set up a Dormant Asset Scheme which channeled funds in accounts that hadn’t been touched in 15 years to charity. Since 2011, it has found £1.35 billion and distributed £745 million.

For Starbucks, it’s not all gain: The company has to pay rewards to its program members, which come at a cost. But at the same time, it saves on merchant discount fees when customers pay via the app rather than by credit card. It also receives lots of free and potentially valuable personal information about its customers.

Adding it all up – 0% interest plus breakage less rewards plus interchange savings plus customer information – Starbucks has created an extremely profitable bank.

Thanks to JP Koning for additional insights.

Carnival

Another company that customers trust to look after their money is cruise line Carnival. The business was even born out of the idea.

In 1966, Ted Arison, a Miami-based businessman approached Knut Kloster, scion of a Norwegian shipping family, with an offer. “You have a ship,” he pitched. “We know she’s doing nothing. We might wind up doing something great for each other.”

Ted invited Kloster out to Miami to show him the market. He had contacts and passenger lists from a previous venture but needed a ship. Kloster owned the Sunward, which he’d used to ferry British tourists to the Mediterranean but when General Franco closed the border between Gibraltar and Spain, business dwindled. “Never mind Gibraltar,” Ted told him, there was more money to be made in Miami than Kloster could possibly imagine. The pair set up a new company, Norwegian Caribbean Lines and that Christmas, the Sunward took 540 passengers on a cruise of the Bahamas.

The business did extremely well. According to Kristoffer Garin, author of Devils on the Deep Blue Sea, the company was soon making more money in Miami than anyone else ever had. Kloster owned the ship and the company name; Ted ran the hotel and entertainment side of the business, handled marketing and dealt with travel agents. “Cruises on the Sunward sold as fast as Ted’s people could take the orders; passengers rolled into the Port of Miami by the hundreds in their tail-finned Buicks and Chevrolets,” writes Garin.

Almost immediately, Kloster began funneling his profits into more ships. Rather than chartering or buying older vessels from other shipowners, the typical practice at the time, he put the capital reserves from his tanker business to work building them from scratch and sent them to Miami as quickly as he could.

Before long, though, Ted realized he had a non-bank bank on his hands. Especially in those days, when information moved at the speed of pens, paper and operator-assisted rotary phones, it was common for passengers to book and pay for a cruise as early as a year before sailing. Under the terms of his contract with Kloster, Ted was responsible for collecting those deposits. Once a given cruise was over, he sent the money to Oslo, but by that time it had been held in a Miami account for a year. As the operation grew, the size of the float grew with it, and soon it was adding up to millions of dollars. Rather than leave it sitting there, Ted invested the money – in cargo ships, real estate and other illiquid assets.

When Kloster found out about Ted’s investment sideline, he wasn’t pleased. In 1971 he hired a team of auditors to go through the books. They found $7 million missing – more than two-thirds of the company’s annual revenues. A Florida judge ruled the audit’s findings were sufficiently damaging to have the company placed in receivership but before the ruling came down, Ted had closed out the company’s bank accounts in Miami and headed off.

It would be years before the pair reached a settlement. The courts eventually ordered Ted to give back around 60% of what he had “seized”. But by then he was already on the way to establishing his fortune, having put the Norwegian Caribbean Lines float to good use one last time. As soon as the scandal broke, he traveled to Europe to buy the first ship for his new startup, Carnival Cruise Lines.

Today, cruise lines continue to enjoy the benefits of float, although they typically invest in operations rather than cargo ships, real estate and other illiquid assets. Recently floated (sorry) cruise line, Viking Holdings, notes in its prospectus that it began selling itineraries for its 2024 season more than two years in advance and that on average for the 2023 season, guests booked 11 months in advance and paid seven months prior to departure.

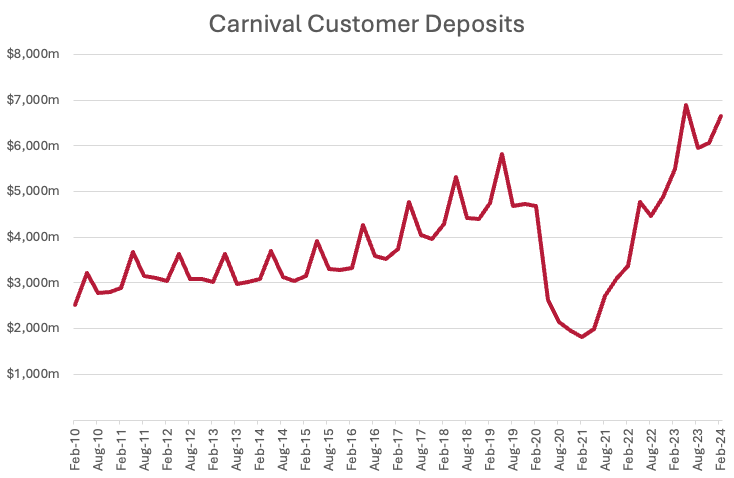

Cash received from guests in advance is recorded as customer deposits on the cruise line’s balance sheet and subsequently recognized as revenue on completion of the voyage. As at the end of February, Carnival had $7.0 billion of customer deposits on its balance sheet, enough to finance a sixth of its property and equipment (principally, its ships). It’s fairly seasonal – cash collections are typically higher in the spring months – but it has grown over time. Operating ships is a capital intensive business, but if customers can shoulder some of the burden, sailing can be a lot smoother.

Thanks to Byrne Hobart at The Diff for the heads up on this one.

Naked Wines

From the outside, Naked Wines looks like a wine merchant. It sells wine direct to consumers in the UK, the US and Australia and boasts almost 800,000 customers. Strip it naked though (sorry) and you find a bank.

The company operates a kind of savings scheme for wine. So-called angels sign up to deposit a fixed sum every month which they can redeem for wine as their balance allows. Full disclosure: I’m an angel. Each month I pay £20 into my Naked Wines account, and just last month I ordered a ‘Highest-Rated Angel Favourites Mixed Case’ for £129.99. The benefits of the model are that by pulling in funding early, the company is able to source quality wines and share the benefits with customers. Rather than receiving interest on their deposits, angels get discounts on a range of wines. My Highest-Rated Angel Favourites Mixed Case came with a 22% discount to its market price of £166.88.

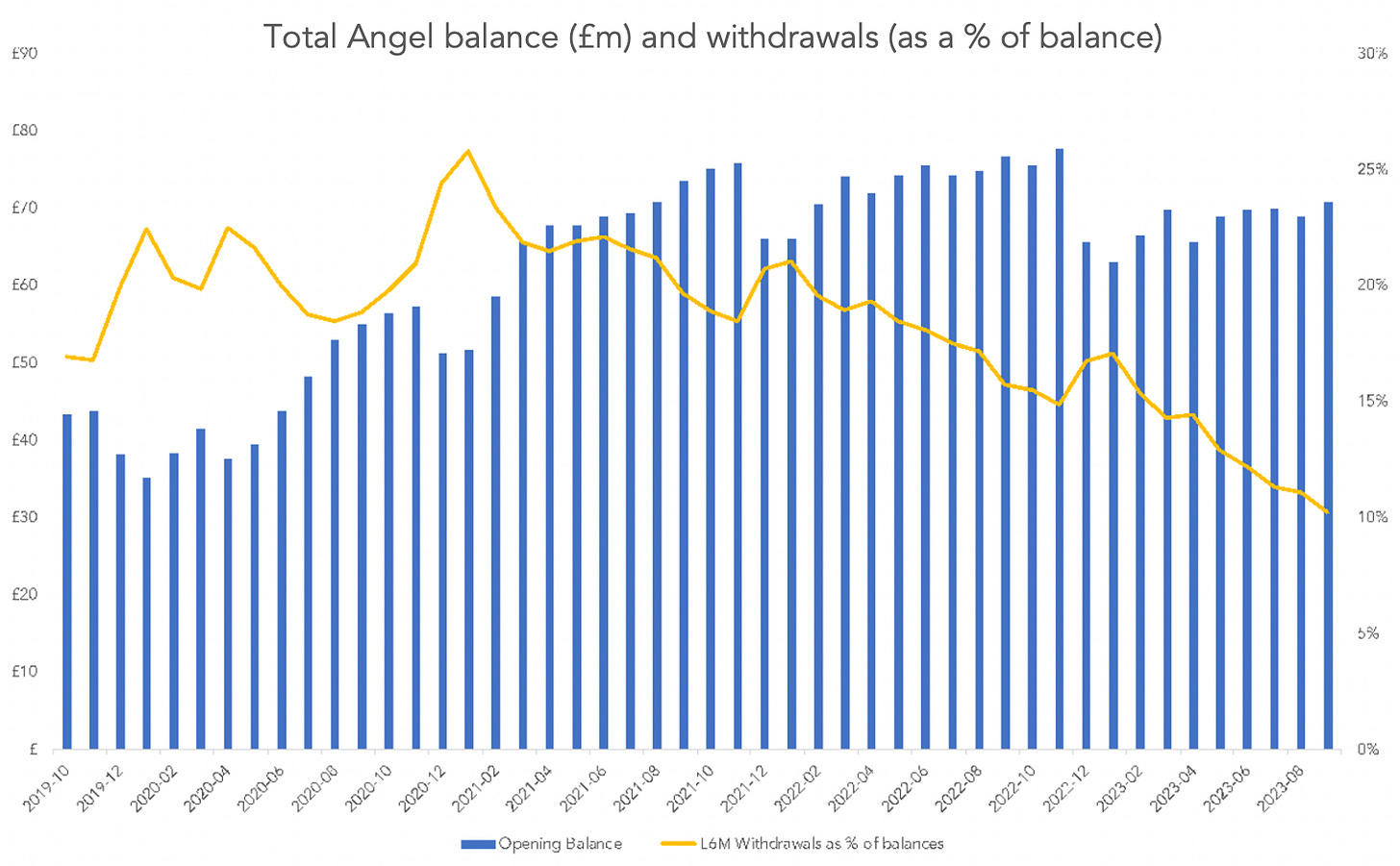

As at the end of March 2023, the company had £67 million of angel deposits on its balance sheet (equivalent to £78 per active angel). These funds finance over 40% of the company’s inventory. The problem is that angel deposits can be withdrawn at any time, without penalty – and after the pandemic, the company experienced a bit of a run.

Once they could re-enter bars and restaurants, many of the angels who signed up with Naked during 2020 and 2021 didn’t stick around. According to the company, in the six months to March 2022, repeat customer sales retention dropped to 73%, from 88% in the prior six months. Having peaked at 964,000 active angels in March 2022 – defined as active subscribers who have placed an order in the past 12 months – user numbers started to decline.

Unfortunately, the company had stocked up on inventory, anticipating continued rapid growth, and was unable to rightsize quickly enough. This led to a liquidity squeeze which, in 2022, auditors said could cast significant doubt on the group’s ability to continue as a going concern.

The company may now be through the worst. Its latest trading update, released this week, reveals that inventory has been reduced by 11%, and a loan note – issued to private equity firm Fortress when it acquired the company’s brick-and-mortar business, Majestic – was redeemed early for a cash injection.

But the episode shows how flighty depositors can be. At peak, 20-25% of angel balances were being withdrawn over a rolling six-month period. The company reckons its customers are now higher quality, with withdrawals tracking at a rate of 10%. As banks know, most of the time deposit duration cleaves to historic behavioral patterns; it’s the other times you have to be careful of.

Delta Air Lines

We discussed frequent flyer programs here back in January, in The Points Guy. Introduced by American Airlines in 1981, it didn’t take long for all airlines to offer them and in 1988 Delta accelerated growth in the market when it launched a Triple Mileage scheme which allowed travelers to clock up points at a turbo-charged rate.

Today, Delta’s SkyMiles scheme is one of the largest globally, with 25 million active members. Its program generated $6.6 billion of revenue in 2023, equivalent to 11% of group operating income. While not a huge proportion of revenue, the business is high margin and so contributes a greater share of earnings. British Airways’ scheme, Avios, for example, operates at a 25% margin, compared with 10% reported by its parent. In addition, the business is more stable, less capital intensive, and not as seasonal as flying planes.

There are two ways points schemes generate money. When a scheme member buys a regular ticket, they are not just buying air travel on a scheduled flight, they are also buying mileage credit they can redeem in the future. Airlines allocate the ticket price between the air transportation and the mileage credits earned. Because customers don’t get the benefit of the mileage credit immediately, airlines defer it, recognising the revenue when points are redeemed and the transportation is provided.

At the end of last year, Delta had $8.4 billion of deferred mileage credits on its balance sheet. Over the course of the year, the company issued $4.2 billion credits while recognizing $3.6 billion worth of redemptions. Although its points don’t expire, Delta anticipates that most will be redeemed quickly – it estimates $3.9 billion will be recognized over the next 12 months; like at Starbucks, though, there is also breakage as some miles languish unused.

The second way schemes earn money is through payments from card companies and other partners. There are various income streams here. Card companies purchase mileage credit, typically at a discount, to allocate to their cardholders; they pay for marketing services, allowing them to send promotional materials to the airlines’ lists of members; and they pay for ancillary services such as lounge access for some cardholders. Delta’s biggest partner, American Express, paid it over $6.5 billion in 2023, a payment that is expected to grow to $10 billion by the time the partnership contract is up for renewal in 2030.

A key question in the whole points dynamic is how much partners pay for miles. Avios Group deferred revenue at a rate of 0.88 pence per point on the stock it issued in 2023, its highest rate in many years. The consumer value of points varies widely according to how they are used, but The Points Guy puts the value of Avios at around 1.2 pence per point, so the benefit to the consumer is clear.

In the US, Bask Bank, an online-only subsidiary of Texas Capital Bank, offers a novel savings account that pays interest in American Airlines AAdvantage miles rather than cash (2.5 miles for every $1 saved annually). For tax purposes, it discloses the value of the miles, which it pegs at 0.42 cents each. According to The Points Guy, their value to consumers is 1.5 cents each, so, again, the discount is apparent.

By minting points, airline companies are able to lock in substantial cash flows. Delta earned $6.1 billion in cash from mileage sales in 2019, the last full year before the pandemic (68% of which was from non-air partners). The value of redemption activity was only $3.6 billion and after other operating expenses of $152 million, that left $2.4 billion of operating cash flow, for a 39% cash margin.

So attractive are these businesses that investors sometimes agitate for them to be spun off. But without them, airlines would be weaker. At the height of the pandemic, Delta argued that SkyMiles is core to its business, contributing to its revenue premium and driving loyalty and consistent customer engagement. Ironically, banks often complain about their low earnings multiples but, for airlines, they are a lifesaver.

Travel + Leisure Co

Not all non-bank banks raise deposits; some extend loans.

Travel + Leisure Co, formerly Wyndham Destinations, sells timeshare units to holidaymakers in America. They don’t come cheap. The average transaction price of a unit is $24,000, according to EY, and there’s maintenance on top, at $1,170 per interval. So to help customers finance purchases, Travel + Leisure offers loans. In 2023, 74% of its so-called vacation ownership interest sales were financed, and although some were financed on a short-term basis, over half (56%) utilized a long term loan.

It’s not unusual for sales companies to offer credit, but most use third-party providers. Retailers don’t want to get involved in resolving delinquencies, recording provisions, collecting bad debts. Travel + Leisure is different. It operates a consumer financing subsidiary which “attracts additional customers and generates substantial incremental revenues and profits.”

Last year, consumer finance contributed $427 million to company revenue, equivalent to 11% of group total (after provisions). But in addition to the direct contribution, consumer finance arguably underpins the whole operation. That is reflected in the number of buyers who rely on finance to complete their purchase, a proportion which has been creeping steadily up over the past ten years:

Like all underwriters, Travel + Leisure investigates a purchaser’s credit history before offering a loan. Its interest rates are determined by an automated underwriting process based upon the purchaser’s FICO score, and average 14.6% on outstanding loans in 2023. The amount of the down payment and the size of purchase were previously also factors in the decision, but these were dropped from the company’s disclosures a few years ago. This may not be surprising: customer FICO scores are typically quite high, at 739 on new originations in 2023, which compares with an average US-wide credit score of 717, a gap which has remained quite stable over the years. But down payments have trended down.

The company typically requires a minimum down payment of 10% and offers consumer financing for the remaining balance for up to ten years. Loans are structured with equal monthly installments that fully amortize the principal by the final due date. Although the average down payment sits above the minimum threshold, it has declined from 30% in 2014 to 19% in 2023.

Travel + Leisure is quite well provisioned for loan defaults, having set up an allowance equivalent to 18% of its $3.1 billion loan book. But provisions are rising. In the first quarter, charge-offs ticked up, and the CFO has indicated that delinquencies may rise over the next couple of quarters. It’s through it now, but the company also weathered a campaign of “induced defaults” where litigation companies helped borrowers get out of their loans.

Underwriting credit is hard, although at least Travel + Leisure knows the asset it lends against. Historically, it was part of an integrated Wyndham hotel group but after a strategic review, credit and timeshare were considered more complementary than timeshare and hotels.

Thanks for reading! Any non-bank banks on your mind? Please let me know by replying to the email or hitting the button below.

The misperception about Harvard is that it’s a hedge fund masquerading as a higher learning institution. It’s actually a diversified alternative investments platform with a university functioning as its marketing / bizdev arm!