Welcome to another issue of Net Interest, my newsletter on financial sector themes. This week we look at Worldpay, a key player in the payments industry, ahead of its spin-off from parent company FIS. Paying subscribers also get access to comments on Commerzbank and Hargreaves Lansdown. To join them and unlock that content as well as a fully searchable archive of 100+ issues, please sign up here:

“He was the future once.” — David Cameron1

If ever there was a company that’s been bounced around, it’s Worldpay. The company traces its history back 25 years and in that time its ownership has shifted from founders, to big banks NatWest and Royal Bank of Scotland, to private equity firms, to public markets – first in the UK and then, following a merger, in the US – to bank technology company Fidelity National Information Services (FIS). Now, just over three years after buying it, FIS has announced that it’s returning Worldpay to public markets via a spin-off.

It’s fair to say that FIS didn’t capture much value from Worldpay during its ownership stint. Having bought it for $33.5 billion in July 2019, the company was forced to take a $17.6 billion impairment charge on its investment with its 2022 accounts. Management bemoans “changing market dynamics” but while the pace may have changed, the dynamics themselves haven’t. Over the past three years, Worldpay merchant transaction volumes have grown by 28% yet newer competitors have grown more: Volumes at Stripe are up 3.8x and at Adyen they are up 3.2x. One time distractions, these competitors are now major adversaries.

As the future itself once, the question facing Worldpay is whether it can fight back as an independent company. To understand what’s going on, we need to go back to the very beginning…

From Founders to Banks

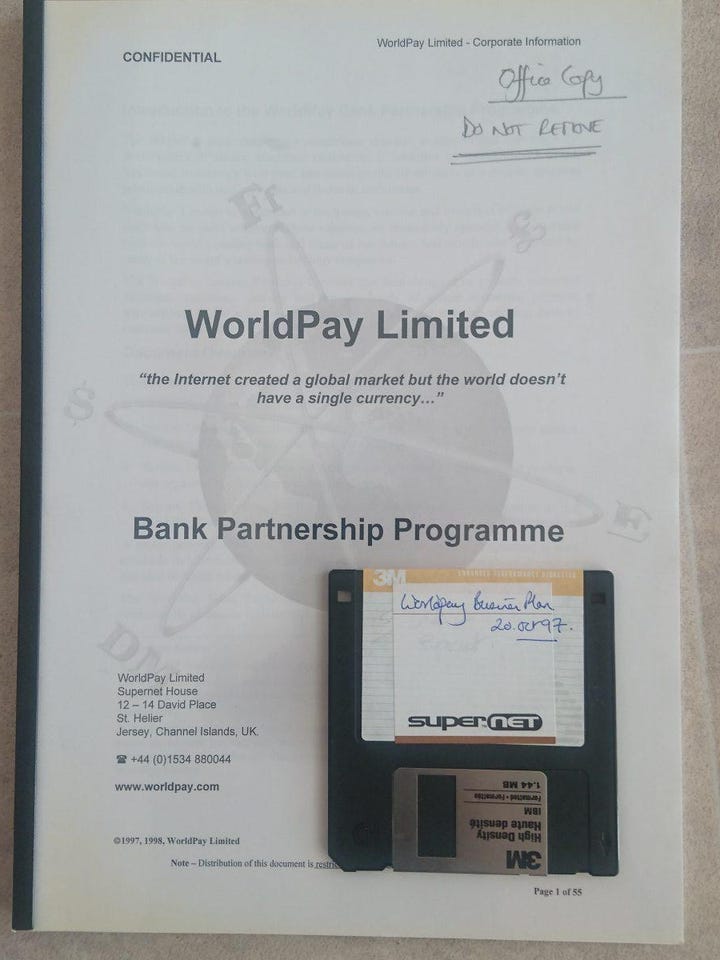

Worldpay was founded in 1997 by entrepreneur Nick Ogden as a solution to a problem he faced running an early online wine store. The store was open to anyone around the world, but prices were fixed in pounds sterling. “I suddenly realised e-commerce wouldn’t work unless we presented goods to customers all over the world in a currency that they understand,” Ogden later recalled. “That was the ‘eureka moment’ behind Worldpay.”

Ogden began working with UK bank NatWest to launch Worldpay as a service enabling companies to accept online payments in local currencies. One of his first customers was the Diana Memorial Fund, after the company was chosen to process online donations following the Princess’s death.

As the market for online payments picked up, Worldpay looked to raise funds via an IPO. But the market collapse in 2000 made that difficult and the founders instead agreed to sell a stake to NatWest for £26 million. Shortly after, NatWest was acquired by Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and the enlarged bank bought Ogden out, assuming full control of the company. By combining it with Streamline, a face-to-face card payment service, RBS turned Worldpay into a full scale electronic payments processing company.

In Growing Visa a few weeks ago, we discussed the architecture that underpins electronic payments. A confession: we simplified. It’s true that Visa and card networks like it sit between bank card issuers and merchants to facilitate payments, but the value chain can be populated with other intermediaries too.

One such intermediary is the merchant acquirer, which acts as a conduit between merchants and the network. Worldpay fulfilled this role. The company sold electronic payment acceptance, processing and supporting services initially to RBS’s corporate customers and then beyond. In this capacity, it routed transactions – whether they originated online or at a point-of-sale terminal – to the appropriate network for authorisation, before ensuring that each transaction was cleared and settled into the merchant’s bank account.

Later, the company also inserted itself between the consumer’s bank and the network, although this part of its business remained small. Fees would accrue largely as a function of transaction activity. For every £100 of consumer spend, Worldpay would pick up around 25p of revenue.

From Banks to Private Equity

As RBS grew to become – briefly – the largest bank in the world, Worldpay got a bit lost. A division buried within a division, it earned £266 million of operating profit in 2009 on revenue of £527 million – a nice margin but too small for management to care. When the bank collapsed during the financial crisis, a condition of its bailout was the sale of the business, and in 2010 a controlling stake of 80% was sold to private equity firms Advent International and Bain Capital for an enterprise value of £2.025 billion. Three years later, they bought out the rest.

Advent and Bain invested in Worldpay’s growth. Including loans, they channelled more than £1 billion into the company, helping to pay for the hiring of some 2,500 people. They oversaw the buildout of a new technology platform, extricating Worldpay from the systems it had shared with RBS, and they funded expansion abroad: By 2015, Worldpay was able to provide access to over 300 payment methods in 146 countries. At home, the company had 300,000 customers and a 42% share of the UK merchant market. The legacy bank links helped – 14% of new customer leads came from RBS – but Worldpay was increasingly finding its own sources of new business.

In particular, the company was a major beneficiary of the growth in e-commerce. By 2015, 43% of its net revenue stemmed from transactions where the card was not present (CNP). Not only was this segment higher growth, it was more profitable: that 25p net “take rate” mentioned earlier represents an average; in e-commerce, the rate was 32p.

The e-commerce angle was a good one to hook public market interest. Keen to cash out, Advent and Bain considered a number of exit alternatives. They turned down a bid from French payments company Ingenico (one was also rumoured to be brewing from Wirecard) opting instead for an IPO. Under their watch, profits had grown – by 2015, Worldpay was doing £406 million of earnings before interest, tax and depreciation on revenues of £982 million – but valuation had grown more. In October 2015, they sold 58% of the company at a valuation of £4.8 billion. Including what they took out along the way, the investment earned the two private equity firms a combined profit of around £3.2 billion ($4.9 billion) in cash and stock.

From Private Equity to Public Markets

The deal was well received by investors (full disclosure: my fund was one of them). But even as it came to market there was a glaring hole in the group’s strategy. With a name like Worldpay, the company had to go global. Yet in the US – the largest electronic payments market in the world – it remained small. Worldpay did have a presence – one that contributed around a quarter of its revenue and 15% of its earnings – but it languished as the ninth largest player in the market with a share of only 3%. And much of that derived from legacy bank links, RBS-owned Citizens Bank accounting for a substantial proportion of the company’s leads.

The difficulty is that the US market was structured very differently from others around the world. While Europe comprises a number of distinct markets, characterised by their own, local card schemes (Cartes Bancaires in France, Girocard in Germany, Bancomat in Italy and so on), the US constitutes one large homogenous market dominated by Visa and Mastercard. A merchant acquirer therefore has an easier task in the US, where there are fewer schemes to integrate. Worldpay management recognised this. On his 2016 earnings call, Vice Chairman Ron Kalifa remarked, “It’s much harder for people who are in the US to actually build the capability outside the US than it is to have one who’s already outside the US to go into the US.”

The flipside is that with little to differentiate the various players, merchant transaction processing in the US became a scale game driven by pricing. Merchants need not know or care who processes their transaction, making processing among the most commodified parts of the payments value chain. And Worldpay’s size made it vulnerable. “Clearly, in the longer term, we want to and we will do much better than the 2% revenue growth we saw in 2016,” said the group’s CEO Philip Jansen on the same 2016 earnings call, referring to the performance of his US business.

Even as they were making these remarks, Jansen and Kalifa were eyeing up an acquisition to bolster their position in the US. Not three months after their IPO, management entered into discussions with Vantiv, the third largest player in the US, about a merger.

Like Worldpay, Vantiv had once been owned by a bank, Fifth Third, which also sold a stake to private equity firm Advent International. Talks continued off and on for 18 months until eventually a deal was announced in July 2017. Worldpay shareholders would be awarded 41% of the combined company, Vantiv shareholders the rest.

The company summarised the benefits thus: “The Merger addresses a historical area of weakness in Worldpay’s US business and provides a platform to expand Worldpay’s leading e-commerce business into the US. and to transfer Vantiv’s integrated technological know-how and capabilities to Worldpay’s global merchant base.”

The problem is that it created a monster. Both companies were already the product of serial acquisitions. Under the ownership of Advent and Bain, Worldpay had done nine acquisitions. Over the same period, Vantiv had done several, including e-commerce payment processor Litle & Co ($360 million) and embedded point-of-sale software provider Mercury ($1.7 billion). Having just rolled out a new technology system at Worldpay, the combined group now had to operate across numerous different platforms.

If scale was all that mattered, this may not have been an issue. Indeed, the deal promised $200 million of cost savings which was later upgraded.

But bubbling under the surface was a new breed of competitor which led not on scale but on technology. In 2004, Worldpay acquired a Dutch company called Bibit as part of its expansion into Europe. Bibit’s team promptly left and two years later set up a new company, Adyen, named for the Surinese for “start over again”. Designed around a single platform that’s easy for merchants to integrate, the company began to make a noise in the market.

In mid 2019, its co-founder and CEO, Pieter van der Does, explained the divergent strategies to investors (emphasis mine):

I think we fundamentally look through a different lens at the market. From Adyen’s point of view, the market is complex and there are new products being launched…think the shift to unified commerce, think about mobile payments, think about QR codes. There’s a constant release of new products, and merchants need a company that can help them there.

But there’s also another way of looking at this industry, and that is payment is a commodity and it's only about scale. If you're looking through that lens, then mergers make sense. If you look at the market through our lens, you would say, “But you just have as many platforms as you had before and now you have to manage all of those platforms. So that’s probably a killer for innovation rather than helping innovation.”

So we feel more confident having a single platform, making sure that we have more than 40% of our employees being engineers, that all those engineers – our merchants are benefiting from their effort. They’re not working integration processes. They’re not working keeping the weaker system up and running. They’re working to their benefit, and we believe that is the right strategy. We’ve always said that we’ve never done an acquisition, and we believe that growing this business as fast as possible in a controlled manner is the best outcome for shareholders.

Adyen’s single unified platform allowed it to gain traction among enterprises with global footprints and omnichannel ambitions. Like other modern acquirers Stripe, Square, Braintree and Shopify, it offers transparent fees, easy onboarding, competitive authorisation rates, and a fast roll-out of ancillary services. In aggregate, this group increased their market share of US merchant acquiring net revenue from 4% in 2016 to 17% in 2021, according to analysts at Credit Suisse. Over the same period, Worldpay lost share, despite an e-commerce offering that ranks more highly than other legacy players’.

From Public Markets to Financial Conglomerate

But once on the acquisition treadmill it’s difficult to get off and in 2019, Worldpay doubled down. Having engaged bankers to explore strategic alternatives for its small issuer processing business, which was growing at low single-digit rates, it contacted several parties to solicit interest in a potential sale. Management got talking to FIS and before long they agreed on a full-blown merger between the organisations.

Remember from the value chain schematic above that issuer processors like FIS interact with banks in the payment process while merchant acquirers like Worldpay interact with merchants. The rationale for a combination was three-fold: that issuer processing data could be used to improve payment authorisation rates, that FIS’s payment networks could be integrated as alternative debit card routes, and that financial institution relationships from the issuer side could be leveraged for merchant referrals. Plus there was scope to take out shared costs across the two businesses. All told, the merger promised $500 million of revenue upside and $400 million of cost savings.

It’s now clear the merger didn’t work. In its most recent quarter, revenue in the group’s merchant solutions business shrank by 1% and guidance is that it will shrink a further 2-4% over the full year 2023. The core e-commerce segment is doing fine – growth there was 16% in the quarter and management anticipates that it will do low double-digit growth in 2023 – but the enterprise and small- and medium-sized business segments are weak and together they make up around 70% of revenues.

But rather than walk back from the pursuit of acquisitions, Worldpay is simply resetting. “The pace of disruption in payments is rapidly accelerating, requiring increased investment for growth and a different capital allocation strategy for our Merchant business,” said Stephanie Ferris, the CEO of FIS.

Management believes that more M&A activity is required to bolster growth and FIS was holding it back. “Specifically, it will enable FIS to pursue a strong investment-grade credit rating while enabling Worldpay to invest more aggressively in growth,” she said of the spin-off.

If any company has learned the risks of injudicious M&A, it’s Worldpay. But, in such a rapidly shifting market, it may have little choice. This time, investors will be more demanding.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this piece, please hit the “Like” button. Better yet, join the community by signing up as a paid subscriber!

David Cameron’s first appearance at Prime Minister’s Questions (PMQs) as Leader of the Opposition was memorable for his quip to the then Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair that “he was the future once”. Eleven years later, Cameron wrapped up his final PMQs, now as Prime Minister, with a reprisal: “I was the future once.”