“We have always had a belief that the Holy Grail is to be able to be an issuer with one’s own network.” — Richard D. Fairbank, Founder, Chairman, CEO & President, Capital One Financial Corporation.

As competitive advantage goes, it’s hard to beat network effects. Strategy consultants list other features: scale, brand, switching costs and the like, all of which contribute to a company’s success, but none are as self-sustaining as network effects. A product or platform whose value increases with the number of people who use it has an in-built advantage, where growth fuels further growth. Once a tipping point is reached, the platform is on its way to omnipotence.

The challenge of course is getting the thing started – what’s known as the cold-start problem. Why would anyone choose to use a new payment device if no-one is going to accept it, a new social media platform if no-one else is on it? Bank of America solved the problem in credit card acceptance by starting small. It focused on the town of Fresno, California (pop: 250,000), where, in 1958, it convinced enough merchants to outsource credit management and enough consumers to trial flexible payments. Once Fresno was done, it rolled the product out across other towns, a model replicated by Facebook years later on college campuses. Eventually, the micro networks joined up to form a larger network that offered more value than the sum of its parts.

But Bank of America didn’t have infinite reach and wasn’t operating in white space the way Facebook was. Although it was one of the largest banks in America, the top ten had a combined share of only 21%. In total, 13,000 banks operated across the country and many developed their own card programs. In the year following Bank of America’s Fresno Drop, some 30 banks gave it a go.

By themselves, most banks struggled, constrained by the small target markets imposed on them by interstate banking restrictions, combined with a lack of engagement from large merchants. Chase Manhattan launched Chase Manhattan Charge Plan in 1958 but was forced to sell four years later when the large New York department stores refused to accept it.

One initial solution was to do joint marketing. As a pioneer in the space and with the benefit of a larger, wealthier home market in California, Bank of America had more success than others (albeit not before it incurred some sizable losses). In 1966, it set up a subsidiary, BankAmericard Service Corporation, to license its card to other banks. Within two years, 254 banks had signed up, each of them further sub-licensing other agent banks in their geography to acquire BankAmericard transactions from local merchants. Through these banks, the network expanded to 6 million cardholders and 155,000 merchants.

As a marketing platform, the system worked well, but operationally and organisationally it was flawed. The system lacked a central clearing facility, so the merchant’s bank and the consumer’s bank would need to settle transactions bilaterally, adding to cost as the network grew. It also faced a tension balancing the zero-sum competitive approach natural to financial institutions with their need to cooperate.

Taking the network to the next level would require a different model, one which Dee Hock, card-center manager from the Seattle National Bank of Commerce and prospective “Father of Fintech”, steered the platform towards from 1970. He understood the size of the prize. “Any organization that could guarantee, transport, and settle transactions in the form of arranged electronic particles twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, around the globe, would have a market—every exchange of value in the world—that beggared the imagination,” he wrote in his memoir years later.

Convincing Bank of America to give up control in favor of a more cooperative structure was not easy. “We invented the *#~*’d system! We own it! We produce 40 percent of the system volume! *#*d if we will be pushed around!” said the Senior Vice President in charge. But Hock persisted and Visa, as his organization became known, reached its tipping point. Chase Manhattan had another go at a solo network, buying back its card business in 1969 but “the second time around proved no more profitable than the first,” according to one historian and eventually it, too, went with Visa.

Today, there are 4.3 billion Visa cards in circulation, accepted by over 80 million merchants. The network did $12.6 trillion of payment volume over the past 12 months. High margins of around 70% allow it to invest over $1 billion a year in marketing and more in business development, helping it to embed those network effects. If it weren’t for antitrust rules and some residual tensions with financial institutions, Visa would have long ago become a monopoly.

The Third Network

One company watching developments from its vantage point at the top of the world’s tallest building in Chicago was Sears. The retailer had introduced store credit to America way back in 1911 when it offered installment payment plans to farmers who couldn’t obtain bank loans to pay for large items in its catalogs. That payment system evolved into a revolving charge account program in 1953, which Bank of America fashioned its own card on five years later. Although it remained tied to a single merchant, that merchant had more market clout than many banks and so the card flourished. In 1978, Sears alone had more cards in circulation than Visa and Mastercard combined.

Dee Hock recognised the role large retailers like Sears played in the market. He was eventually ousted from Visa in part for his attempt to bring merchants directly onto the network, disintermediating banks. “Many bankers refuse to realize that many large retailers can do everything a bank can do, and often better,” he told American Banker magazine in 1979.

Recognising this, too, Sears decided to build a network of its own, inviting other merchants onto its platform. In 1985 it acquired Delaware based bank, Greenwood Trust and, under the guidance of senior vice president for corporate administration, Phil Purcell – who would go on to run Morgan Stanley – launched the Discover Card a short while later.

The company leveraged its existing customer base to seed its network. By the end of 1989, it had placed 33 million cards in more than 20 million households, equivalent to 20% of American homes. It recruited merchants at an even faster rate, onboarding 1.1 million, equivalent to two in every three card-accepting merchants in the country.

After cumulative losses of $230 million over 1986 and 1987, Discover reported profits of $107 million over 1988 and 1989. Most profits came from lending balances: Unlike peers, the card did not charge an annual fee. It also pioneered the idea of cash rewards, initially at a rate of up to 1%, to incentivise usage. For merchants, the proposition was lower discount rates – it generally charged 2% compared with 2.5% for Visa and Mastercard and 4% for American Express – and more information about consumers. By operating a “closed loop” that didn’t involve other banks, there was no interchange and Discover could share the benefits with customers. Its line of sight straight into the consumer’s wallet – lacking in the case of open loop networks like Visa and Mastercard – allowed it to offer targeted deals, such as 10% discount on Saks purchases.

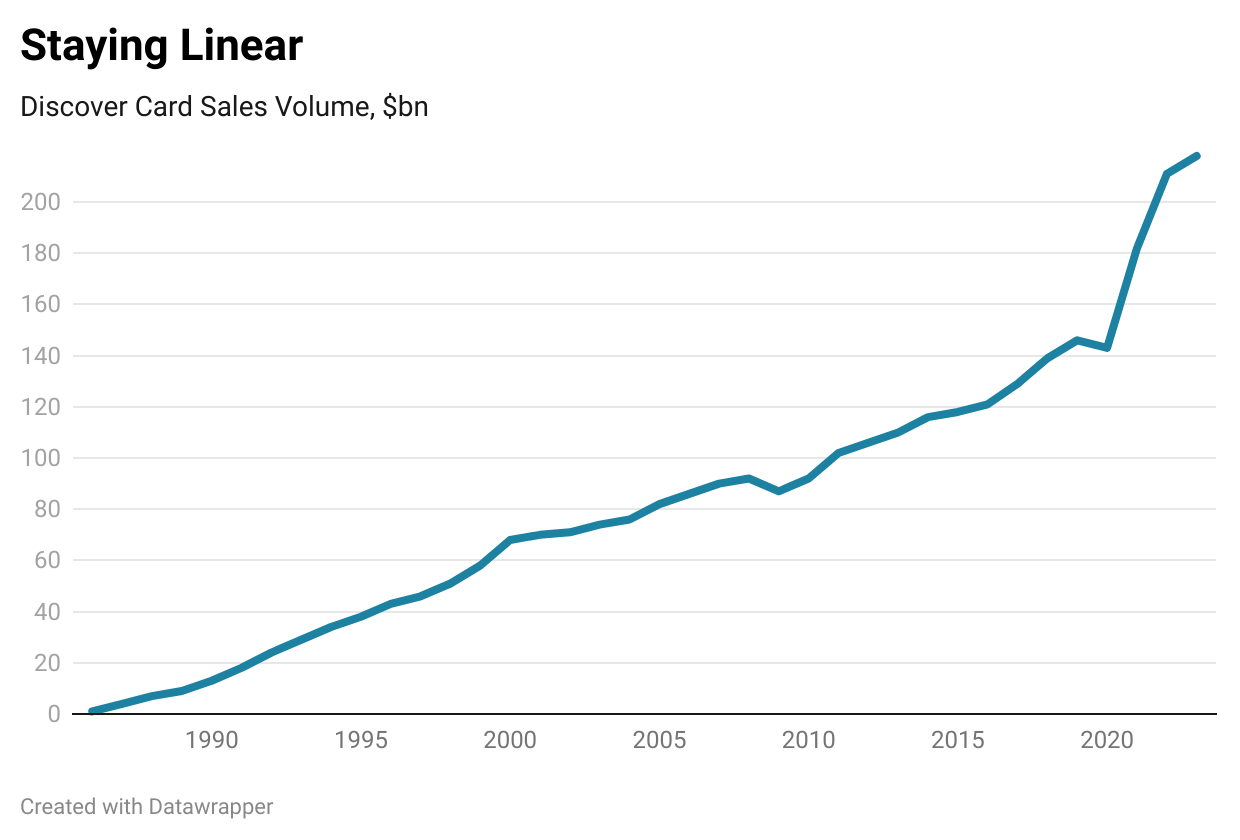

In 1993, Sears spun off Discover alongside its brokerage business as Dean Witter, Discover & Co. As an independent company, the network continued to grow, although it never attained the tipping point Visa had and so growth remained linear rather than exponential. In its 1996 annual report, the company laid out some challenges: “Our second challenge is merchant parity with Visa and MasterCard. Right now, Discover and other NOVUS cards are accepted at outlets that account for about 90 percent of total U.S. bankcard transactions. That's not bad for a relative newcomer competing against two powerful, established associations. We’ve been expanding our merchant network every year, but we won’t be satisfied until we get close to 100 percent.”

Part of the problem was Visa and Mastercard themselves. Since 1991, Visa had thwarted competition from Discover through exclusivity rules forbidding banks from issuing Discover or American Express cards, on pain of forfeiture of their right to issue Visa. The rules were challenged by the Department of Justice and ultimately overturned in 2003, but for Discover it was too late. It wasn’t the only issue holding Discover back – a damages settlement of $2.75 billion struck with Mastercard and Visa would have been too low if it was – but it didn’t help.

For a while Discover was owned by Morgan Stanley, which acquired Dean Witter, Discover & Co in 1997, but in 2007, Morgan Stanley spun it back out as Discover Financial Services. It remained an independent company for 17 years, growing a third-party debit card network it acquired in 2005 after exclusivity rules were outlawed, expanding its book of credit card loans, making complementary acquisitions such as Diners Club, which it bought in 2008, and investing and then divesting in other areas such as student loans.

This week, Capital One announced the acquisition of Discover. A key part of the rationale: getting its hands on the network. Will the issuance volume behind it be enough to push Discover through its tipping point and mount a challenge to Visa and Mastercard? Read on.