Housing the Young

The Crisis in the Structure of British Housing

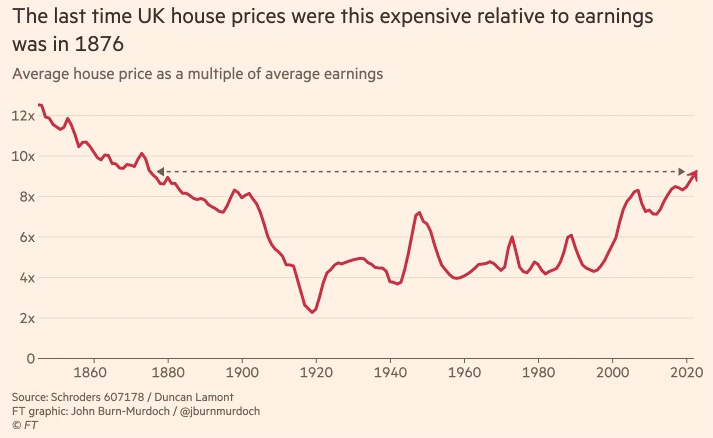

When I bought my first home, in a trendy part of London over 25 years ago, house prices in the capital were four times median income. Today, the multiple is 12 times. Having taken me two years of toil in the City to save for a deposit, it takes current workers 30 years. That makes no sense. Across the UK, houses haven’t been this expensive relative to earnings since 1876.

This time next week, the UK will have a new government, and towards the top of its to-do list will be to resolve the housing crisis currently gripping the country. A top-four issue for voters, according to polling company YouGov, escalating house prices have put the dream of homeownership out of reach for many. As well as diverting resources from other spending (rental payments now account for £85.6 billion per year), the impact on productivity, inequality, innovation and other areas of life has been well-documented.

There are a number of factors that explain how the situation got this bad: Supply, and demand – obviously – but also the mechanism that would normally balance them. Let’s take a look at each in turn. For paid subscribers, there’s a bonus section on Vistry Group, one of the UK’s largest and most innovative homebuilders. Its CEO had some candid advice for the new government in a newspaper op-ed today.

I. Supply

First, supply. It wasn’t obvious when I bought my first home, but a decline in the rate of house building was already impacting market dynamics. In the 1950s and 1960s, house building rates exceeded 1.9% a year in the UK; by the 1990s, the rate had fallen below 0.8%. Such slow increases to the housing stock compound. According to the Centre for Cities, had the UK built houses at the rate of the average Western European country over the sixty years to 2015, a further 4.3 million homes would have been available, increasing the stock by 15%.

Such a gap is consistent with other estimates of the backlog. An influential report published in 2018 estimated there were 4.75 million households in need of housing across the country, including from adults who would prefer to live separately from their current households. The report makes use of a methodology to address a circularity problem prevalent in this kind of analysis, where household projections are based on historic formation trends even though they may be suppressed by a lack of available housing.

Its author, a professor of urban studies in Edinburgh, proposed that the backlog could be shifted if homes were built at a rate of 340,000 per year (in England) over 15 years, later suggesting that his estimate “might be shaded down a little towards 300,000 in the light of demographic events”. It’s a number consecutive governments have run with.

Yet, having promised to build “300,000 homes a year by the mid-2020s”, the last Conservative government delivered 226,000 new homes in its final full year of office. Labour has committed to getting to 300,000 by building 1.5 million new homes over the next parliament.

So why is it so difficult?

The first reason is planning. The rise of nimbyism is a well-known phenomenon. I see it where I live. Not far from my house, developers lodged a proposal to convert a disused nursing home into a complex of 41 properties. The plans looked nice, the site was derelict anyway, and there is a clear need for more houses in the area, but the proposal attracted more than 200 objections from local residents – including many living in a new development across the road, completed only a few years earlier. The scheme was eventually approved after much time and expense.

Although 80-85% of planning applications typically do get approved, the process puts many applicants off. At no point in the past two decades has the number of planning grants exceeded 300,000 a year, making it impossible to build that many new homes. In the last reported 12 months, the number across England was 286,000.

Part of the problem is that local authorities have complete discretion over the process, so no one knows what the outcome of their development proposals might be. This contrasts with most of continental Europe, where a “rules-based” system is prevalent. In England, instead of all land being available for development unless it is prohibited, development is prohibited on all land unless a site is granted a permit. And although local authorities are given guidance from central government, only a third of them had a valid legal plan in place as of July last year, giving them cover to pander to nimbys.

Meanwhile, the costs and complexity associated with filing an application escalate. Local planners take an average of well over a year to reach an outline decision, at a direct cost of between £100,000 and £900,000 to the developer depending on the size of the site, according to the Competition and Markets Authority. In my day, you could buy a house for that!

No fan of it, Rachel Reeves, in all likelihood the UK’s next Chancellor of the Exchequer, calls the planning system, “the single greatest obstacle to our economic success”.

But it’s not just the fault of local authorities. They are obligated to provide services for the additional residents without a corresponding boost to their longer-term finances, diminishing their incentives. The Town & Country Planning Act of 1947 that handed them discretion over planning affairs also rendered large parts of the country unbuildable, introducing green belts that locked cities within their 1950s boundaries. England overall is currently 8.7% developed but 37.4% protected.

The good news is that although you wouldn’t want to build in a flood zone (10.3%), that still leaves 43.6% of land available for development. The Labour Party proposes turning some of that into “new towns”. Most people might prefer to live in old towns – indeed, economic activity would prefer they did – but it’s a start.

II. Demand

That’s the supply-side diagnosis. Demand-side factors have additionally had an impact on the level of affordability. They emerge distinctly because housing is as much a financial asset as a place to live. And, like all financial assets, its valuation is linked to interest rates.

Making UK housing especially financial in character is its highly liquid private rental market. We discussed this in Generation Rent around eighteen months ago. Back in 1996, the Housing Act was amended to make shorthold tenancy the default rental agreement, allowing landlords to sign up tenants on a fixed term of between six months and five years while retaining the right to regain possession afterwards. The point, according to a white paper issued beforehand, was to ensure that “the letting of private property will again become an economic proposition”.

And so it did. The terms of the tenancy agreement made rental properties a lot easier to finance. No lender wanted the burden of a sitting tenant in a repossessed home; the short-term nature of the new contract mitigated that risk. A new, cheaper class of loan – the “buy-to-let” mortgage – emerged to replace the commercial mortgages landlords had used previously.

Landlords were drawn into the market, enticed by the stable cash flows thrown off by rental properties in an environment of low interest rates and volatile securities prices. They were also better equipped than first-time buyers to finance larger down payments imposed by lenders following the financial crisis. As a result, by 2014, the number of loans granted to landlords outstripped the number given to first-time buyers. Nearly 200,000 buy-to-let mortgages were approved in one year alone. Between 2005 and 2015, almost every net new home added to England’s housing stock ended up in the private rented sector.

Today, there are 1.98 million buy-to-let mortgages outstanding in the UK, compared with 8.72 million homeowner mortgages. Around one in every 21 adults in the UK is a landlord.

Alongside the excess demand from landlords, pockets of demand have also been created by various government schemes. The biggest, “Help to Buy” which ran from April 2013 to October 2023, was ironically set up to address the affordability crisis but, by offering subsidies to homebuyers, it did little to dampen prices. The scheme, “which will have cost around £29 billion in cash terms by 2023,” concluded a House of Lords report, “inflates prices by more than its subsidy value in areas where it is needed the most.”

It also helped enrich homebuilders, who themselves have a hand in the affordability crisis.

III. Market Structure

New build is a small part of the overall housing market in the UK, accounting for just 11% of housing market transactions over the past ten years, according to the Competition and Markets Authority. But as producers of most of the marginal supply, homebuilders have a big influence over market dynamics.

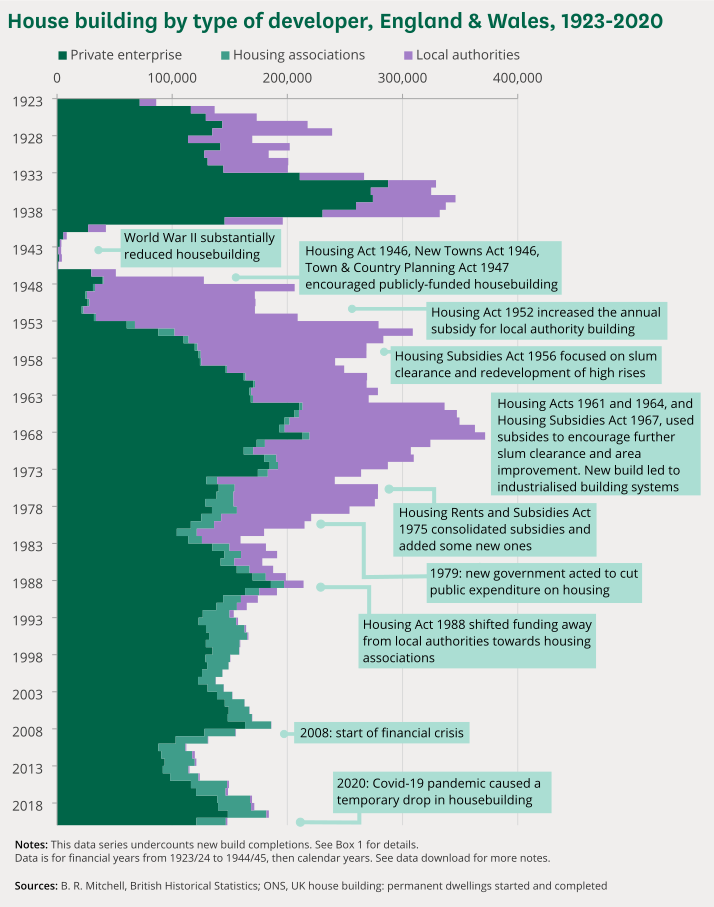

For thirty years following World War II, local authorities built their own houses. At the peak of new home delivery in 1968, when 372,000 homes were completed, 43% were built by social housing developers, and 57% by the private sector. By the 1980s, though, local authority contributions had fallen, with the government looking to cut public expenditure on housing and, alongside the Housing Act of 1988, funding was shifted away from local authorities altogether.

But private sector builders never delivered the same volume, and in each successive cycle their output steadily declined. Clearly, that is linked to incentives. Private housebuilders employ a speculative model, where they buy land in advance without knowing the final price at which they will sell the homes. Around 60% of the new build homes completed last year were built on this basis, with the bulk of the rest (30%) reserved for affordable housing – funded or procured by a public body, or provided by housebuilders as a condition for receiving planning permission for the rest of the development.

The model puts an emphasis on margin over both volume and speed of delivery. Instead of building houses as quickly as possible, homebuilders tend to complete them at a rate which maximizes sales price and keeps the stock of built and unsold homes to a minimum. This arises partly because homebuilders value land on the basis of its development potential (residual valuation model), partly because planning constrains the availability of further local supply, and partly because firms don’t have much pricing power, overshadowed as they are by the existing home market.

In times of rising prices, though, homebuilders have an incentive to hold onto land. “We said that we weren’t just a house builder, we were a land portfolio company,” said the CEO of Taylor Wimpey, a top three builder on his call with investors in 2016. “Our main driving goal – our main way of adding value – was adding value to the landbank, taking it through the planning process. We still believe that today.”

At the end of 2022, the top 11 homebuilders in the market sat on a landbank of 1.17 million plots, according to the Competition and Markets Authority, with an average life of 7 years. Stripping out the very long term land parcels that have a low chance of being developed, the remaining land had been held for an average of 4 years.

The industry’s strategic focus on margin increased following the financial crisis. After earning a return on capital in excess of 20% in the years before the crisis, returns fell sharply negative in 2008 and 2009. To recover their position, homebuilders conserved cash and prioritized margin. “It used to be about volume, I think, in the olden days,” said the CEO of Barratt Developments, another top-three builder, on his earnings call in 2009. “It’s now very firmly about did we hit the numbers, did we deliver the prices that we expected.”

“I want to re-emphasize this, our focus is on growing those margins, so we're not out for volume for volume's sake,” echoed the CEO of Persimmon two years later. Sure enough, while the output of new homes grew 70% between 2010 and 2017 among the top nine (to 76,000 units versus 70,000 in the year before the financial crisis), revenues increased by 178% and pre-tax profit by 703%, to £4.8 billion.

As another driver, homebuilders went for scale. In 1980, the biggest ten private housebuilders produced 28% of new national supply; by 2015, the biggest ten were producing 47%. Small- and medium-sized developers, although still active, were squeezed out while the largest players consolidated. Today, the top three produce between 20% and 30% of total supply.

Given these incentives, it’s hard to see the private sector stepping in to resolve the housing crisis. Enter a new model: partnerships. Just last year, one of the UK’s largest homebuilders, Vistry Group, overhauled its strategy to pursue this model. Fashioned after NVR Inc. in the US – one of the best performing stocks in the market over 20 years – the model offers a modern take on local authority housing development, with private market efficiency.

To learn more, read on.