Family Fortunes

The Origins and Growth of the Family Office

Thank you for being a paid subscriber to Net Interest, my newsletter on financial sector themes. This week, I’m excited to share a guest post by one of my favourite writers, Frederik Gieschen. Frederik is the author of Neckar’s Minds of the Market, where he analyses the minds and methods of the world’s greatest investors. Inspired by Bruce Lee – “Absorb what is useful, discard what is useless and add what is specifically your own” – Frederik researches the lives of great investors, picking out key lessons from their journeys, which he recounts in a captivating way. Among my favourites are his series on Stanley Druckenmiller and Bill Miller.

In this post, Frederik turns his attention to family offices. Family offices command a huge pool of capital yet often operate in the shadows of pension funds, endowments and other allocators. Bill Hwang may have thrust the structure into the spotlight when he blew up his own family office a year ago, but they’ve been around a long time. Frederik’s post explores their origins and their growth. For more on how they invest, Frederik has expanded his piece at Compound. I hope you enjoy it.

Family Fortunes

Today, thousands of family offices collectively invest an estimated $6 trillion in assets. With flexible long-term capital they can be active across markets and asset classes, becoming key investors particularly for smaller investment managers and deals. And yet most of them remain practically invisible.

The birth of the modern family office happened almost by accident. Its success led to a windfall profit in one of the early 20th century’s most notable mergers.

Rockefeller, Gates, and the family office archetype

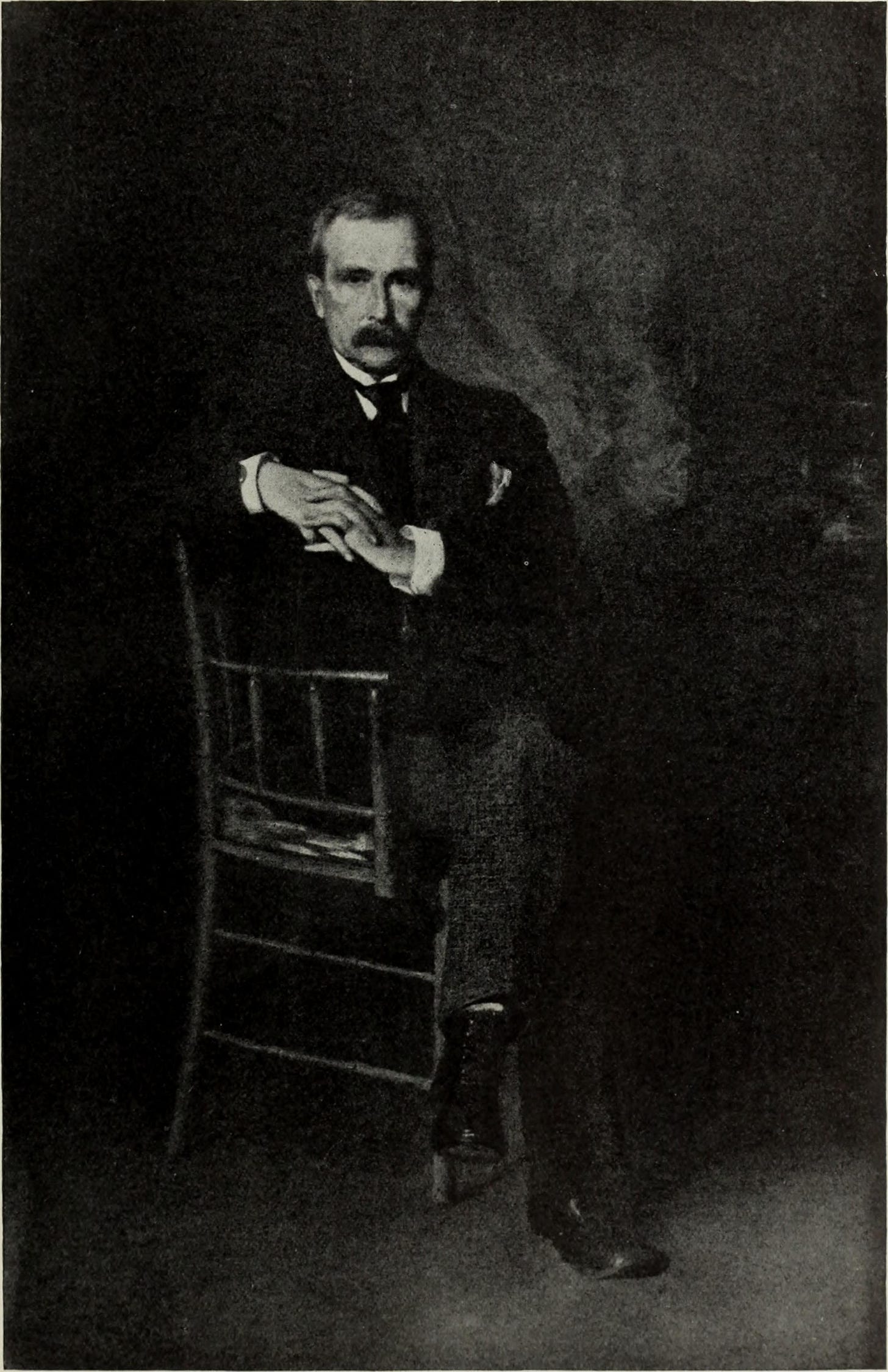

In 1901, U.S. Steel, America’s first billion-dollar corporation, was formed through the merger of several steel companies. One unlikely winner of this transaction was John D. Rockefeller who owned a vast iron mine property, Wisconsin’s Mesabi Range. This homerun investment dated back to a moment when Rockefeller’s personal portfolio was, frankly, a mess. It lacked professional oversight and was littered with bad and even fraudulent investments. It was also the birth of the modern family office.

As Ron Chernow recounted in Titan, his Rockefeller biography, by 1890 Rockefeller was well-known for both his wealth and his charity. As a result, Rockefeller was being “trailed by a small army of petitioners,” a situation that was exhausting the otherwise private business tycoon. That year, he met a young Baptist minister named Frederick T. Gates who would change the trajectory of Rockefeller’s philanthropy and fortune.

Rockefeller asked Gates to help with the “avalanche of appeals” and Gates noted in his own biography that Rockefeller was “hunted, stalked and hounded almost like a wild animal.” Retail philanthropy, as he called it, was unsustainable. Gates had helped in the fundraising and structuring of a Baptist school and helped Rockefeller structure a first attempt at wholesale philanthropy: the establishment of the University of Chicago.

Rockefeller found himself isolated by his wealth, lamenting that nearly all of his interactions were tainted by money. He even became wary of making new acquaintances in business. Playing golf, by “the ninth hole out comes some proposition, charitable or financial.” Gates, “skeptical by nature,” became Rockefeller’s trusted confidante who unleashed his investigative talents on his personal portfolio. Rockefeller had no dedicated portfolio manager and was a minority investor in a variety of ventures brought to him by supposed friends. He needed someone to audit his investments without the risk of embarrassment if an outside analyst “might broadcast his failures on Wall Street.”

Gates took one of Rockefeller’s luxurious private trains and started visiting the tycoon’s properties, from money-losing iron furnaces in Alabama, to phantom mines in the Rocky Mountains, and real estate scams in Wisconsin. In his presentation on Gates, Peter Kaufman described how Gates set out “like a great detective” in his due diligence effort, “verifying recorded documents in county record offices, interviewing objective third party experts, even chatting up miners on a Colorado train.”

Confronted with the poor state of his investments, Rockefeller gave Gates “unrestricted access to his files for all investments outside of Standard Oil” and moved him into his main office on 26 Broadway. The young minister found himself in charge of the turnaround of “some twenty of these sick and dying corporations.” He divested many assets but also reinvested capital, for example in large timber land in the Pacific Northwest. There Gates even co-invested with Rockefeller and the tracts eventually fetched “five or six times their purchase price” and compensated for other losses.

But Gates' biggest coup was Wisconsin’s Mesabi Range. This venture started like the others: as a blunder, a collection of mining properties brought to Rockefeller by promoters cloaked as friends. It included the Minnesota Iron Company which, to Gates’s surprise, seemed to hold a lot of potential. A local family of entrepreneurs, the Merritts, was in the process of developing a rich vein of iron ore. The ore was powdery, and America’s steelmakers had not adapted their furnaces to use it. The development of the mine and transportation infrastructure would require significant capital, but Gates believed the deposit was, “the opportunity of a lifetime.”

In a sign of how strong the bond of trust had grown, Gates was able to shield Rockefeller from interactions with the Merritts, explaining that, “in talking to me, you are talking to Mr. Rockefeller.”

Rockefeller consolidated his holdings with those of the Merritts in a new holding company, the Lake Superior Consolidated Iron Mine. Plenty of capital was required to construct infrastructure such as railroads and docks, and Rockefeller became the primary source of capital. Gates even acquired a fleet of nearly sixty vessels to carry the ore across the lakes. The panic of 1893 offered an opportunity to take control of the mine. Rockefeller’s infusions of capital increasingly diluted the Merritts’ ownership stake and eventually he provided a mortgage loan which provided him seniority in the capital structure. Even though the Merritt family had started the development, at a crucial moment they found themselves at the mercy of Rockefeller’s balance sheet.

In 1901, Rockefeller and Gates sold the company and fleet of vessels to the newly formed U.S. Steel for $88.5 million. Chernow recounted that Gates estimated the profit at $55 million. Instantly, Rockefeller became the second-richest man in America behind Andrew Carnegie. Watching the windfall from the sidelines, the Merritt family later sued Rockefeller who, skeptical of getting a fair trial, chose a settlement rather than “submit to larger robbery by the twelve just and good men.”

Gates became part of a new executive committee overseeing Rockefeller’s personal assets. He and his colleagues justified their salaries to Rockefeller with a simple pitch: Paying them was considerably cheaper than “being robbed as you have been without exact knowledge as to many of the investments in which you have large sums involved.” Due to the size of Rockefeller’s portfolio, Chernow described the family office as a “one-man investment bank” and a key player on Wall Street.

Gates continued to take his role as philanthropic advisor seriously, spending his evenings “bent over tomes of medicine, economics, history, and sociology, trying to improve himself and find clues on how best to govern philanthropy.” He helped Rockefeller create a more systematic way of giving away his wealth, in “scientific fashion that befit the scale of his fortune.” Rockefeller’s fortune established the medical school at Johns Hopkins University, the Rockefeller Institute (now Rockefeller University) in New York, and the Rockefeller Foundation.

Gates also took on the role of a business tutor for J.D. Rockefeller Jr., taking the boy with him to audit meetings and on trips touring the “iron ranges in Minnesota and timberlands in the Pacific Northwest.” According to Chernow, Gates “gave him the guidance he sorely missed from his father.”

Gates and his colleagues reflect the archetype of the modern family office: it started with the desire for an “entirely independent agent,” as Gates called it, and became a dedicated team of confidantes tasked with personal finances, philanthropic efforts, legal matters, and even the education of the next generation.

Origins and growth

The concept of staff overseeing a family’s household and wealth can be traced back to the maior domūs in ancient Rome (Latin for “principal of the house”), the highest-ranking servant entrusted with the household's most important affairs. And some European family offices can trace their origins back to the management of large landed estates. But the modern family office has its origins in the U.S. and coincided with the creation of industrial fortunes.

However, wealth creation alone is merely a prerequisite and doesn’t necessitate the creation of a dedicated team. A fortune does not necessarily need dedicated management if it is concentrated in a small number of assets, such as a family-controlled corporation, and if ownership is consolidated in the hands of the founder.

The desire for tailored and unbiased advice and discretion is also not enough of a reason. For some time the functions of family offices were carried out by outside advisors including private banks and trust companies instead. Lisa Gray noted in her history, How Family Dynamics Influence the Structure of the Family Office, how the model of the European private banks was “carried to the New World by the likes of Alexander Hamilton [and] John Pierpont Morgan.”

Instead, she argued that an increase in complexity was often a key factor behind the creation of a family office. She pointed out the “thorny questions” raised by liquidity events: “Should the money be dispersed or managed collectively? How much control should following generations have and how early? How much control does the founder want to retain? What is the governance structure for shared partnerships? How does control pass through generations?”

Management and governance complexity can increase dramatically once a fortune is liquid and reinvested in a variety of assets and owned by multiple generations and family branches. The growth of family offices was not just driven by wealth generation but by liquidity events (the sale or public offering of family-owned companies) and the complexity arising from inheritance and estate planning.

While large companies could achieve liquidity by going public, the rise of private equity created a new wave of liquid wealth creation for owners of mid-size companies.

“It wasn’t until the 1980s that family offices started to multiply,” John Davis of Cambridge Family Enterprise Group explained in the Financial Times, “first in the US, then elsewhere. It was around that time that the wealth held by families began to grow at a significantly faster rate.”

More recently, hedge fund managers retiring from managing external capital often convert their firms into family offices. And venture-backed startups typically aim for liquidity through a sale or IPO which leads to the creation of liquid wealth among both founders and employees. As a result, many wealthy technology founders have their own family offices.

Complexity can increase dramatically once the wealth is passed on from the founding generation. Gray writes that the founder’s singular voice is “multiplied through siblings and cousins,” and through estate planning, families can find themselves with a myriad of trusts and partnerships. In The Complete Family Office Handbook, Kirby Rosplock wrote that Rockefeller Jr.’s “elaborate estate planning and gifting,” prior to President Roosevelt’s tax increases, established “the model for transgenerational wealth transfer” and protected the family’s fortune. The New York Times described how Rockefeller Jr. created generation-skipping trusts for the benefit of the grandchildren and following generations which avoids an instance of estate taxes. Complexity can also be driven by the portfolio, particularly by investments in illiquid or controlled assets that require oversight.

Structures and functions

In The Way Forward for Family Offices Credit Suisse outlined the three common family office structures. First, the embedded family office, an “informal structure within the family-owned business.” The chief financial officer or other employees take on duties for the family and coordinate external advisors. They still report to the company’s chief executive officer who in turn reports to the family (or is a member of the family).

The stand-alone single family office is a separate legal entity serving only one family. It can be involved in the management of a variety of the family’s assets, including the investment portfolio, any family-controlled companies or real estate, and manage other assets as well as plan liquidity. It is overseen by the family though the structure of governance varies.

Each office uniquely reflects the needs, legacy, and structure of the family it serves. The breadth of services differs but typically includes investment and liquidity management as well as administration and concierge services. The degree of outsourcing of accounting, tax, legal and other services varies substantially as shown in a survey by Credit Suisse.

Finally, there is the multi-family office (MFO) which serves multiple separate clients. MFOs are fundamentally different in that they are essentially third-party-owned wealth managers that charge a fee and are regulated as investment advisors. Single family offices on the other hand enjoy an exemption to registration. MFOs are both regulated and, rather than organic extensions of one family’s needs, are profit-driven businesses. They are the preferred choice if a family’s wealth doesn’t warrant the expense and complexity of creating a dedicated office.

MFOs can emerge from single family offices, for example out of a desire for greater scale to invest in talent and technology. Andrew Carnegie’s partner Henry Phipps Jr. created Bessemer Trust upon the sale of Carnegie Steel to U.S. Steel. According to Rosplock, by the 1970s Bessemer had a staff of 200 and was no longer cost efficient, paying out an estimated two percent of assets under management. The Phipps family recognized the need for greater scale and reorganized the company to become a wealth manager for other affluent families. More recently, after the death of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, his family office Vulcan Capital spun out its investment manager as a multi-family office.

Even the Rockefeller family office eventually followed this path. By 1992, the New York Times wrote that the number of family clients had grown to 100 and the in-house Rockefeller Trust Company was managing nearly 300 family trusts. The family office with 200 professionals at 30 Rockefeller Plaza adjusted its mission to reflect a “new emphasis on growth." Given the family’s substantial philanthropic commitments, David Rockefeller Jr. explained the need to “rebuild the per-capita wealth.” Today, Rockefeller Capital is a multi-family office managing $95 billion of client wealth.

However, this is not a common occurrence for two reasons. First, the objectives are fundamentally different: a tailored bundle of services for one family compared to a scalable commercial offering. Second, the MFO structure introduces a completely different degree of regulatory oversight. It is rare for a relatively informal single family office to be retooled for this. It is more likely for a new MFO to emerge when a team of wealth managers leave an established firm.

If you are interested in how some well-known family offices invest, keep reading at Compound.

Programming note: No More Net Interest this week as I’m still on vacation, but if you have any suggestions for future posts, or would like to pick up a thread on something I’ve written before, please do get in touch – it would be great to hear from you. My email is: marc@netinterest.email.

Very interesting and detailed, many thanks!