Welcome to another issue of Net Interest, my newsletter on financial sector themes. Every Friday I distil 25 years experience of looking at financial institutions into an email that explores key themes trending in the industry. I’m grateful to all of you who have signed up, but don’t keep it to yourselves! Spread the word to followers, friends, colleagues, anyone. Thanks!

Buy Now Pay Later

Credit cards are big business. There are over a billion of them sitting in American wallets. They drive $1 trillion of lending and earn their issuers over $100 billion in revenue.

But is that revenue safe?

Over the past few years a group of companies has emerged, intent on disrupting the credit card business. These companies – one from Australia, one from California and one from Sweden – sell a product called Buy Now Pay Later, and it’s proving quite popular.

The Australian company, Afterpay, is the only one that’s publicly listed; its stock is up over 2,500% since IPO three years ago.

The Californian one, Affirm, filed a confidential prospectus last week ahead of a listing of its own, in which it is reportedly seeking a valuation of $5 to $10 billion.

And the Swedish one, Klarna, the biggest of the three, received funding in September valuing it at $10.65 billion.

All three have benefited from the migration of shopping to the internet over the period of the pandemic. To understand what they do, why they have been so successful and whether that can continue, we take a detailed look at Klarna.

In order to set the scene it’s worth winding the clock right back to the earliest days of the credit card. If that’s the business they want to disrupt, it may carry some lessons.

The Fresno Drop

The credit card was born one mid-September day in 1958. After a period of planning, Bank of America mailed 60,000 freshly minted cards out to customers in the city of Fresno, California.

People were familiar with the raw concept of a card. Diners Club had launched eight years earlier after its founder famously left his money at home and found himself unable to pay for lunch. But Diners Club was a charge card—customers had to settle their account in full at the end of every month and couldn’t use it to access credit. If it was credit they were after, people could either apply for a line of credit from the store they wanted to shop at – Sears being the pioneer here – or go to a bank for a loan.

Bank of America’s cards were different—they came with pre-approved credit that could be used at any store where the cards were accepted. They combined the payment functionality of Diners Club with the access to credit of a bank loan. Unlike the bank loan, the customer was in complete control—they could pay it all back at once, or they could pay it back in installments, and they could choose over what time period to pay those installments.

The Bank of America card programme was the brainchild of Joseph Williams. Many of the features he developed are still in use today, such as the one-month grace period customers have before they start incurring interest. Even the prevailing interest rate of ~18% a year, equivalent to ~1.5% per month, was embedded in Williams’ very first credit cards.

One problem Williams faced was how to incentivise both consumers and merchants to use the card. Like any two-sided platform, value comes from high rates of adoption on both sides. However popular it is on one side, the programme would fail if adoption was not balanced on the other.

The merchant side turned out to be easier than anticipated. Although the fee Bank of America wanted to charge merchants was high – 6% of the purchase price – merchants saw that it would remove a huge headache from their back office. Small merchants who ran their own credit books had to maintain monthly accounts, chase collections and manage working capital. Now they could outsource all of that to Bank of America. By launch, more than 300 shop owners had signed up.

On the consumer side, Bank of America gave the cards away for free. Williams chose Fresno as the testing ground because its population was large enough (250,000) to offer a critical mass and the bank had a dominant market share there (45%). The cards were mailed out and an advertising campaign launched (“Carry Your Credit in Your Pocket!”).

The programme was beginning to look exciting. But rather than wait for the results of Fresno to come in, Bank of America became spooked by the prospect of another bank launching a competing card. So they scaled up. They introduced the card into San Francisco, Sacramento and Los Angeles. Within 13 months of the Fresno launch, around 2 million cards were in circulation, with 20,000 merchants signed up.

It didn’t go well.

Williams was a great innovator but he wasn’t a credit guy. As credit companies throughout the ages have learned, credit is a difficult beast to manage. Offer people money today against the promise that they pay it back at some later date, and many will take advantage. Williams had predicted that delinquencies would average 4%; they hit 22%. Fraud was rampant. No provision for collections had been made. Its foray into credit cards cost Bank of America $20 million including advertising and overhead—no small amount in the late 1950’s.

Nevertheless, Bank of America forged ahead, albeit without Williams. The early teething problems were resolved, and adoption grew. In his 1960 report to shareholders, the bank’s CEO predicted that credit cards would soon become “a significant source of earnings”. The losses turned out to be a blessing—they kept competitors at bay. For eight years, Bank of America had the California market to itself.

Over subsequent years the market grew. Retailers like Sears still captured a large share of consumer credit but by the late 1970’s, bank-issued credit cards were catching up. Bank of America’s card processing business would become Visa. Merchant acceptance grew, consumer usage grew and after a few decades, credit cards became priceless.

Until now?

Introducing Klarna

The CEO of Klarna, Sebastian Siemiatkowski, said recently:

“You have this credit card industry which in general has charged massive interest rates, a lot of late fees, has been a not very transparent and great industry, and I think actually the big opportunity is for people like us...and others to disrupt that industry. It’s the credit card industry that we’re going after.”

Sebastian Siemiatkowski founded Klarna in 2005 with two friends, towards the end of his time as a student at the Stockholm School of Economics. The three saw huge problems in the way that online retail was being conducted in those early years. Debit cards had higher penetration than credit cards in Sweden but consumers didn’t like using them online for goods they were yet to receive.

The three thought they had a solution to the problem and pitched it at an angel event—in the presence of the King of Sweden, the chairman of H&M and other prominent business leaders. They came last but managed to raise some seed capital elsewhere and went on to launch the business under the name Kreditor Europe, which they later changed to Klarna. (In the days before the financial crisis, fin carried more cachet than tech.)

Their first product was an after-delivery payment product. Customers would provide Klarna with their details; Klarna would pay the merchant; and the customer would reimburse Klarna after 14 days on receipt of an invoice. Merchants liked it because it led to a 20% increase in conversion rates at checkout.

Like in all good startup stories, the founders worked hard, taking five days vacation in two years; there’s even a photo of them hard at it in their office during the summer months. Unlike in other startup stories, though, they made money. The business was profitable within six months.

The company ploughed its profits back into the business and went on to raise external capital from Sequoia, General Atlantic and others in order to expand. It entered new markets and launched additional payment solutions. The solutions differ across countries, but the key ones are:

Installments. Customers can split their purchase into four equal payments.

Financing. Customers can finance larger purchases over 3-36 month plans.

Pay in 30 days. An evolution of the original product, customers can pay after they’ve had time to try the product.

In developing their product, Siemiatkowski and his team faced the same challenges Joseph Williams did 60 years earlier when he rolled out his credit card: how do you grow the consumer side and the merchant side?

The proposition on the consumer side is plain: less friction and free credit. For the installments product, and the ‘Pay in 30 days’ product, the consumer doesn’t pay a fee (unless they’re late)—the merchant does. Friction is reduced to just a single step in the installments product, which the company reckons takes 25 seconds even if the customer doesn’t have an account with the merchant.

On the merchant side it’s a bit more tricky. None of that back office outsourcing stuff works anymore—merchants have that covered. And with fees at 6% of purchase price, merchants are being asked to foot a steep discount, equivalent to what Williams charged Bank of America’s merchants all those years ago. The answer lies in higher sales activity.

According to Klarna:

Retailers typically see a 68% increase in average order value with Installments.

58% boost in average order value for retailers offering Financing.

20% increase in purchase frequency for customers shopping with Pay in 30 days.

In addition, the company claims that 44% of users would have abandoned their purchase if a mechanism to pay later wasn’t available.

Originally, the company came to market via the merchant side (helped by some smoooth marketing to give it credibility with consumers). In 2017, it launched an app to target the consumer side. The app has features that provide users with shopping inspiration and after sales services. This year, the app was upgraded to include a shopping browser which allows users to navigate across different stores, compile a wish list, receive notifications of price changes, manage digital receipts centrally, track delivery and more.

Yet even while it was doing this, Klarna was expanding its footprint in banking. The company is unashamedly structured as a bank. It holds customer loans on its balance sheet, and funds them with deposits. This year it began offering deposits in Germany in partnership with fintech Raisin (0.00% for overnight money, if you’re interested). As at end June, it had SEK33 billion loans on its balance sheet, funded by SEK24 billion of deposits. Siemiatkowski argues that banking has traditionally been about deposits and lending, with payments being “a kind of boring infrastructure piece” that banks haven’t focused too much on. He’s coming at it the other way round. He’s also keen to embrace banking regulation because of the trust it confers.

So is Klarna a bank or an e-commerce company? Here’s what Siemiatkowski has to say:

“We try to not think too much about letting the category we're in define what we're doing. We don't think, we're a payments company and hence we do payments things. We're trying to look at what are the problems that people are facing today, what are the experiences that we could enhance…”

Scaling Up

Last year the company took a strategic decision to scale up. It took in $460 million of funding from investors – including Snoop Dogg who fronted a marketing campaign – and launched its app in the US. Klarna had been present in the US since 2015 and launched its ‘Pay in 4 installments’ product into the market in 2018, but it was really last year when it gained traction.

By mid 2020 Klarna had grown its US consumer base by 6.5x to almost 9 million consumers. Its app has had 6.1 million downloads in the past 12 months and 2.4 million monthly active users in the past 30 days. On both measures it ranks higher than Afterpay or Affirm. It has 4,300 retailers signed up, including H&M, Sephora, Ralph Lauren, The North Face and Timberland.

[Source: Apptopia]

It may seem odd that a consumer credit company is going global. Consumer credit products are typically regulated at a local level. Although credit card networks operate globally, most credit card issuers remain local to specific markets. But online shopping is inherently more global than offline and Klarna follows its merchants around the world. Globally, it now works with over 200,000 retailers, many of whom have international brands.

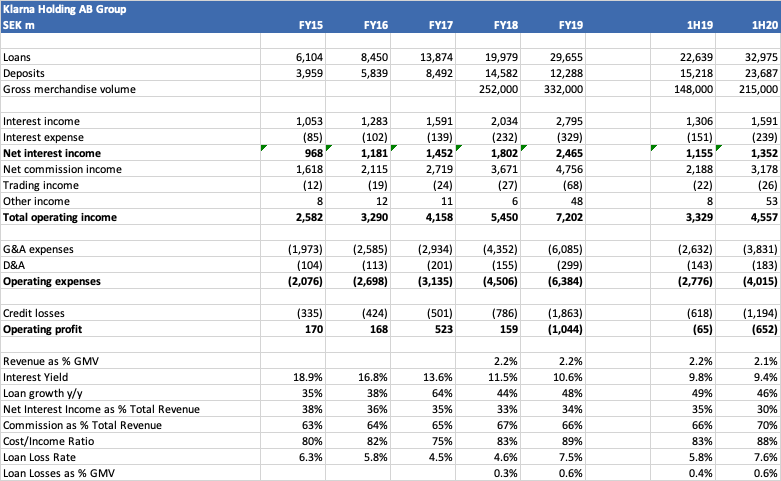

The investment in US expansion put a dent in Klarna’s track record of annual profits. Last year it reported an operating loss of SEK1 billion. In banking terminology, its cost/income ratio rose from 75% in 2017 to 89% last year. That ratio was sustained into the first half of 2020, when the company incurred a loss of SEK652 million.

Another way of interpreting these numbers is that Klarna’s revenue generation is so high, it is able to absorb huge investment spend. Its operating expenses over the 18 month period have been SEK10 billion ($1.1 billion), which, coupled with the capital it raised to cushion the losses, amounts to some pretty impressive firepower (and Softbank isn’t even a shareholder). It compares with around $200 million spent over the same time period by Afterpay.

Klarna earns revenue at a rate of around 2.1% on its gross merchant volume. In the first half of 2020 that volume was SEK215 billion ($22 billion), up 44% year-over-year, so revenues are growing at quite a clip. However, the revenue rate may come down going forward. At the beginning of 2019, around 34% of revenue came from interest income on the loan book. As non-interest paying products like installments grow, the weighting of interest income in the mix may shrink; it was already down to 30% in the first half of 2020. Given an average interest rate of 9.4% on loans, that could make quite a difference.

Instead, the company relies more on commission income, which makes up 70% of its revenue. This is split three quarters from merchants and one quarter from consumer late fees. The company is making an effort to minimise late fees in response to negative publicity. In Australia, Buy Now Pay Later operators have come under pressure to cap late fees and, in the US, Affirm does not levy them. One of the ways Klarna is doing this is via direct consumer engagement within its app.

A key challenge for Klarna, as it was for Joseph Williams and the Bank of America team sixty years earlier, is credit. The reason Klarna suffers a loss even though costs are less than revenues (i.e. its cost/income ratio is less than 100%) is because of credit losses. In the first half of 2020, it suffered credit losses equivalent to 7.6% of its loan book (annualised). At the end of 2019, around a fifth of its book was past due, with 6% of its loans more than 30 days past due (these numbers are not available for the first half of 2020, unfortunately).

This credit quality isn’t as good as Affirm’s, based on recent securitisation data. But it looks similar to Afterpay. As a percentage of the total sales it finances, credit losses come out at 0.6% of sales, which compares with 0.7% at Afterpay over the same period.

[Source: company reports]

Impending Disruption

So far this year, the main Buy Now Pay Later companies have financed around $40 billion of sales, globally (around half of which is Klarna). Compared with the $10 trillion credit spend that passed through the pipes of Visa, Mastercard, American Express and Discover, that’s a drop in the ocean. So how much of a disruption threat are these players?

The upside is that the market is coming to them. Credit card lending hasn’t grown an awful lot since Joseph Williams died, in 2003. In the past 15 years US credit card lending has grown at a compound rate below 1% a year. One of the reasons is the low take-up by millennials. Just one out of three millennials carries plastic at all, and those that do tend to prefer prepaid or debit. This is exactly the demographic that Klarna and the others are targeting. The average age of a Klarna customer is 33.

As with similar models that target a younger demographic, the question is whether preferences change with age or whether the new market will grow with them. In the meantime, Klarna can deploy its experience of a debit led culture in Sweden into the US millennial market.

Against that, there are a number of challenges:

First, Buy Now Pay Later is not conducive to all consumer spend. Siemiatkowski himself says that when it comes to groceries for example, they are best paid for directly. The Australian Financial Industry Association estimates that 30% of Australians use Buy Now Pay Later services, but that doesn’t make it a massive market.

Second, credit cards consolidate all spending, and packages it into a single monthly bill. That may be a more convenient solution than dealing with multiple Buy Now Pay Later bills.

Third, the competitive environment will no doubt heat up. Visa is developing an installment infrastructure which it plans to offer to financial institutions on its platform. Some card companies already have the functionality, for example, Citi Flex Pay. PayPal recently announced a ‘Pay in 4’ product in the US and a ‘Pay in 3’ product in the UK.

On the competitive side, Klarna may have a few advantages. Banks could be reluctant to push the product too much for fear of cannibalisation, especially as profitability in their revolving card business is higher than in the Buy Now Pay Later business. Meanwhile, as a regulated bank, Klarna has a suite of products to offer and its payments hook is a cheap way to acquire customers (especially if subsidised by merchants). The company argues that unlike Visa, it has a full line of sight into what products its customers are buying and can use that data to provide enhanced services.

Perhaps the biggest feature the Buy Now Pay Later model has going for it is that it is fundamentally more robust than the credit card model, in that it does not rely on consumer cross-subsidisation. Technology is enabling greater personalisation. In fintech that is evident within insurance. Root argues that it can measure risk based on individual performance and so doesn’t have to resort unfairly to bucketing people in discrete risk groups. It’s similar in the credit card industry. By bundling together various services – the charge service, the credit service, rewards, others – some consumers end up overpaying, others underpaying. The picture is laid out pretty neatly in this paper, which uses a dataset of 160 million credit card accounts. In the case of Buy Now Pay Later, consumers don’t subsidise each other; the merchant subsidises everyone.

Joe Nocera’s book, A Piece of the Action, provides a fascinating account of the history of the credit card.

More Net Interest

Digital Wealth Management

Nutmeg is a digital-only wealth management business founded in the UK in 2011. It was known for heavy advertising on the London Underground in the days when people used the London Underground. It reported its results for financial year 2019 last week and they reflect a key challenge faced by all fintechs, especially those asking you to give them your money: customer acquisition is expensive.

In its nine years of existence, Nutmeg has incurred £103 million of operating expenses. Around half of those are staff costs but assuming 75% of the rest are marketing costs, it has spent £40 million on marketing. For its money, it has acquired 80,000 customers. That’s a big number; it makes them the fifth largest wealth management firm in the UK by number of clients. But they’re not yet paying their way. The cost of acquiring those customers works out at ~£500 per head, and they generate revenue at a rate of ~£150 per year per head.

The problem is that it costs a fixed sum to acquire a client, but the revenue they generate is a function of how many assets they bring with them. The average Nutmeg customer has £25,000 lodged in their Nutmeg account, and pays fees at a rate of 0.60% per year, hence the £150. It would certainly cost more to acquire a customer with £2.5 million under management, but not necessarily 100 times more. So Nutmeg operates at an inferior point along the CAC/LTV curve compared with other wealth managers. And any reduction in running expenses afforded by operating at this point, where customers are happy with a digital-only relationship, is offset by the cost to acquire.

Central Bank Digital Currencies

Earlier in October, the European Central Bank published a report examining the possible issuance of a digital euro and kicked off a consultation period. The Bank for International Settlements followed up with a joint report laying out key requirements for central bank digital currencies. The European Central Bank has given itself until mid 2021 to decide whether to embark on a digital currency project.

There are benefits and there are drawbacks. Unlike other means of digital payments, a digital currency could be used anywhere, just like cash today; it could be designed to be easy to understand and use; and it would increase privacy through the involvement of central banks who have less commercial interest in consumer data.

The drawback is the potential disintermediation of banks. For the first time, retail customers would have access to central bank money. This leaves banks at risk of losing deposits to central bank digital currencies over time, making them more reliant on wholesale funding. They would also lose their relationship with customers, achieved through payments (even if, as the Klarna CEO says above, payments is an area banks have traditionally underinvested in). Policymakers have been bashing banks for years, now they really have them in their sights.

Rapid Disruption

For a case study in rapid disruption, look towards Kazakhstan. Kaspi, the country’s largest fintech company, listed in London this week. Its stock price immediately rose 25%, bringing its market cap to $8 billion. Why? Rapid disruption. The company used to be a consumer lending company but pivoted to payments in 2019. It built a closed-loop payments platform, modelled on Alipay in China, which it launched in the middle of the year. Its market share of electronic payments was initially 2%, with Visa and Mastercard taking 96%. By mid 2020 its share had ramped to 66%, leaving Visa and Mastercard with just 28%. Not a big country, but perhaps Visa and Mastercard should take note.

India is also seeing some great startups in this space.

Thanks for writing this. Do you have any pointers to similar writings on afterpay & affirm with some data int hem? please share if you have any