Battle of the Buttons

How PayPal, Amazon and Shopify are Changing the Checkout

It’s shopping season and, after a post-pandemic break, activity continues to migrate online. Adobe Analytics estimates that US shoppers will make $221.8 billion of online purchases in the final two months of 2023, up 4.8% on last year and equivalent to 20% of overall spending. On Black Friday itself, e-commerce sales were up 8.5%, according to Mastercard SpendingPulse, outstripping in-store sales growth of only 1.1%

For retailers, all that traffic means a frenzy at the checkout. Although online shopping has been around for a long time – my Amazon order history stretches back over 20 years – payments is a problem that is still being solved. Around one in seven online card transactions fails to go through, according to payments company Adyen, as authorisation rates of around 85% lag the 96% typically attained in the physical world. For the consumer, the need to enter a string of 16 digits plus some other numbers and then follow a set of instructions to confirm the transaction confounds the experience and often leads to purchases being abandoned.

One of the first companies to address the problem was PayPal. In late 1999, founding COO David Sacks wrote a product spec for a “button” that could be installed on merchant websites to provide “a single-click payment system for the entire web.”

“The idea sounded laughable, but its implications were significant,” writes Jimmy Soni in his history of PayPal, The Founders. “Strategically, a focus on buttons catapulted the company into a space with few rivals.”

Initially, the project was called X-Click, in deference to Elon Musk’s passion for the letter X, though it was later renamed Web Accept. Sacks’ paper expounded on its business case: “The product’s inherent network effects meant the first mover will have a tremendous advantage. Every day we have the market to ourselves is an irreplaceable chance to build an insuperable lead.” The business model envisioned that whenever a consumer who had not yet registered with PayPal visits the website of a merchant with Web Accept installed, the consumer would have to open a PayPal account from the merchant's site in order to make a purchase.

Sacks anticipated that other “tightly integrated payment competitors like eBay/Billpoint, Yahoo/dotBank, and Amazon 1-Click/zShops” would remain so focused on home turf payments that they’d miss PayPal’s spread across the web. Indeed, by the time PayPal listed on the stock market in 2002, Web Accept was available through the company’s 3.2 million business customers.

Sacks was right about the focus of those integrated competitors, although he may have underestimated the reach of one. Amazon’s zShops project failed (“no customers,” wrote Jeff Bezos in his 2014 shareholder letter) but it morphed into Marketplace – now home to 310 million users – and brought with it the Amazon 1-Click technology.

In 1997, Amazon launched 1-Click technology, at the time hailed as an innovation due to its ability to allow visitors to make purchases with a single click without having to re-enter billing, payment or shipping information each time. By making the checkout fast and simple, the feature created an important advantage for Amazon in the online marketplace. In September 1999, Amazon secured a patent for 1-Click ordering after it sued Barnes & Noble for implementing a similar technology called Express Lane. The patent allowed Amazon to protect its technology from other online retailers and platforms in the US for a period of 20 years.

At about the same time, Amazon acquired internet payments startup Accept.com for just over $100 million. Its founders envisioned a service that allowed users to pay anyone, for anything, anywhere online. Yet once integrated into Amazon, their efforts were deployed on solving Amazon’s internal payments problems, including combating fraud. It wasn’t until 2013 that Amazon created a “Pay with Amazon” button for non-Amazon storefronts.

By then, PayPal had a clear market lead outside the Amazon ecosystem. Web Accept had become Express Checkout and it boasted more than ten times the number of active users and merchants as its closest competitor. PayPal made money by charging merchants whenever their customers used the button and earning a spread between those fees and the cost to process transactions. In cases where consumers used a card to fund the purchase, the cost comprised interchange and network fees. In a high proportion of cases, though, consumers used balances sitting in a wallet on PayPal’s balance sheet or a direct debit out of a bank account, and the spread was higher. Overall, the button drove around three quarters of PayPal revenues.

When PayPal came back to the stock market in 2015, it warned of “substantial and increasingly intense competition.” One such source of competition was Apple. Back in September 2000, Apple had licensed Amazon’s 1-Click ordering technology and later incorporated it into iTunes and the App Store but, like at Amazon, its use was limited to making shopping easier only within its own ecosystem. In 2014, Apple launched the iPhone 6 with a new service, Apple Pay, installed as a pre-loaded feature.

Apple Pay was a game-changer in payments technology, according to Capital One CEO Richard Fairbanks. It pioneered the use of near-field communication (NFC) reader chips embedded in phones to establish a wireless connection between the user’s device and a compatible point-of-sale. By using anonymised tokens to keep the customer’s payment information private from the retailer and biometric information such as Touch ID (fingerprint) or Face ID (facial recognition) it enhanced payment security considerably. “Card numbers are not going to be embedded inside the secured element on a phone,” explained Fairbanks. “Instead, one-time single-use or a-few-times-use tokens will be, in a sense, sent to the phone. So that the risk of extended fraud is massively reduced.”

Adoption was initially slow. In 2017, the Wall Street Journal reported that only 13% of the 680 million iPhone users had used Apple Pay. Unlike PayPal, Apple Pay was designed for the offline world and growth was hampered by a requirement to build out the relevant infrastructure. But as that happened, usage picked up. In 2014, when it was introduced, only 3% of retailers in the US had the infrastructure to accept contactless payments. That number is now 90% and Visa reports that 40% of US transactions are now contactless, up from 5% in 2020. The proportion of iPhone users currently using Apple Pay has risen to 75% at the same time as the number of iPhones in circulation has gone up, to over 1.2 billion.

Adoption offline has led to greater adoption online, particularly over mobile. The company doesn’t provide a split, but one estimate suggests Apple Pay has a 6.2% share of online payments in the US. It makes money by charging the underlying card issuer a small fee – 0.15% of the transaction value for credit card payments in the US (less in Europe where interchange rates are lower) and a flat 0.5 cents on debit card payments. The company justifies its cut on the basis that its improved authentication technology lowers the cost of fraud when cardholders use Apple Pay.

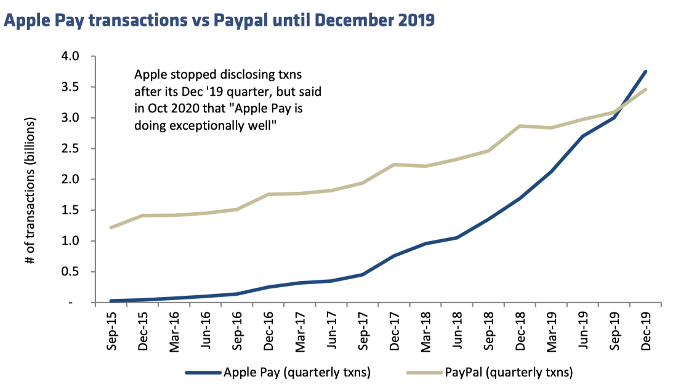

At the end of 2019, Apple stopped disclosing the number of transactions that take place over Apple Pay but in its last disclosure, CEO Tim Cook reported that activity is “exceeding PayPal’s number of transactions and growing 4x as fast.”

Coming off the pandemic, PayPal’s growth decelerated sharply. The company reacted by promoting its “unbranded” alternative to merchants who also featured the PayPal button on their checkout page. Through Braintree, a company acquired in 2013, PayPal offers merchants a gateway they can white label to accept debit cards, credit cards and other payment methods from consumers. It’s lower margin to begin with but PayPal slashed pricing further to subsidize growth in its core business. The strategy caused a slowdown at Adyen, one of Braintree’s major competitors, as we discussed in The Capital Cycle Hits Payments a few weeks ago. Nor does it appear to have worked. Data from Salesforce suggests that PayPal usage was down 5% year-on-year in the US during Cyber Week, and down 14% in the weeks before Cyber Week.

Instead, under new CEO Alex Chriss, the company is reportedly working on upgrading its online checkout facility. According to The Information:

As part of the overhaul, pieces of which PayPal executives mapped out for analysts in June, the company is creating a new, more efficient version of its online checkout that will recognize a user’s email address and immediately send a one-time login code to their phone, rather than making them enter their username and password in a pop-up window. This streamlined checkout will work even if shoppers don’t have a PayPal account, as long as they have saved their shipping and payment information with at least one of the 35 million merchants that use PayPal.

For some, the button’s new functionality may look familiar. That’s because it resembles the Shop Pay button used by Shopify.